Trends of Per-Patient Healthcare Cost and Resource Utilization of Opioid Use Disorder Among Privately Insured Individuals in The United States from 2005-2014

Article Information

Bibo Jiang*, Li Wang, Douglas Leslie

Department of Public Health Sciences, College of Medicine, The Pennsylvania State University, Hershey, PA, 17033

*Corresponding author: Bibo Jiang. Department of Public Health Sciences, College of Medicine, The Pennsylvania State University, Hershey, PA, 17033

Received: 26 September 2023; Accepted: 04 October 2023; Published: 21 October 2023

Citation: Bibo Jiang, Li Wang, Douglas Leslie. Trends of Per-Patient Healthcare Cost and Resource Utilization of Opioid Use Disorder Among Privately Insured Individuals in The United States from 2005-2014. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology Research. 7 (2023): 203-212.

Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Total healthcare cost and resource utilization associated with treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) has increased drastically in the past twenty years as the opioid epidemic continues to escalate. However, little is known about the changes in per-patient healthcare cost and resource utilization of OUD over time.

Objectives: To investigate the trends of per-patient healthcare cost and utilization of outpatient, inpatient and emergency department services among privately insured individuals with OUD from 2005 to 2014.

Methods: The MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters database was used. A matched case-control design was employed to estimate the impact of OUD on healthcare cost and service utilization over this period. In particular, we investigated the trends of excess per-patient healthcare cost and its components including inpatient, outpatient and drug costs. We also compared the utilization of outpatient, inpatient and emergency department services between OUD patients and non-OUD control subjects.

Main findings: The excess annual per-patient healthcare cost for OUD remained relatively stable with an average excess cost of $14,586 between 2005 and 2014. However, excess outpatient costs increased while excess inpatient costs decreased over time. Among OUD patients, the increase in the OUD-related outpatient care utilization rates and the average number of visits coincided with a decrease in inpatient and emergency department (ED) service utilization rates and average number of ED visits.

Conclusions: The increasing per-patient utilization of OUD-related outpatient care, together with a decline in the per-patient utilization of more urgent care, including inpatient and emergency department care, might suggest an increased awareness, diagnosis and better management of the disease among existing patients with private insurance. Efforts focused on increasing access to OUD treatment are crucial in combating the opioid epidemic.

Keywords

opioid use disorder; healthcare cost; healthcare resource utilization; emergency department; inpatient care; outpatient care

Article Details

1. Introduction

The misuse of and addiction to opioids, includingprescription pain relievers,heroin, and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, is a serious national public health crisis that affects the social and economic welfare of the United States [1].The nonmedical use of prescription pain relievers grew from 11.0 million to 12.5 million between 2002 and 2007 [2]. In 2010, an estimated 12.2 million people reported using pain relievers nonmedically for the first time within the past 12 months [3]. In recent years, a sharp increase in the use of illicit opioids including heroin and illicitly manufactured fentanyl has also contributed to the increase in opioid overdose [1]. Drug overdose deaths nearly tripled from 1999 to 2014, with over half of the drug overdose deaths in 2014 involving an opioid [1, 4-6]. Opioid-involved overdose death rates further increased by 15.6% from 2014 to 2015 and 27.9% from 2015 to 2016, resulting in 42,249 deaths (13.3 per 100,000 population) in 2016 [5, 7]. A key driving factor in the overdose epidemic is underlying opioid use disorder (OUD). Consequently, expanding access to addiction treatment services is an essential component of a comprehensive response [8]. Like other chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, addiction is generally refractory to cure, but effective treatment and functional recovery are possible [9].

However, given its high mortality and morbidity, OUD has imposed substantial costs on payers and society, and inflicted clinical burdens on the healthcare system. Birnbaum et al. estimated that the total cost of prescription opioid abuse, including direct and indirect costs, reached $55.7 billion in 2007 compared with $8.6 billion in 2001 [10,11]. According to a review of studies published from 2002 to 2012 on the U.S. economic burden of opioid abuse when compared to a control group, the mean excess healthcare cost for opioid abusers with private insurance ranged from $14.054 to $20.546 and from $5,874 to $15,183 for opioid abusers with Medicaid [12]. In two more recent studies by Rice et al., the excess annual per-patient healthcare cost of diagnosed opioid abusers was estimated at $10,627 and $11,376, using two different datasets of privately insured individuals [13,14]. In addition to research on excess healthcare costs, there are studies focusing on the clinical burdens of OUD. These studies found that, in general, OUD patients utilized more healthcare services, including ED visits, outpatient visits, and inpatient hospital stays compared to non-OUD control subjects. With an increase in the prevalence of opioid abuse and dependence, drug treatment admissions related to prescription opioids increased more than fivefold between 1998 and 2008 [15]. The rate of hospital stays involving opioid overuse among adults increased more than 150 percent between 1993 and 2012 [16] and ED visits for opioid overdose quadrupled from 1993 to 2010 [17].

The aforementioned studies, among others, either studied the trends of the total healthcare cost or the clinical burdens associated with treatment for OUD or estimated the excess healthcare cost of OUD by following patients’ treatments for a short period, often 12 months after the first OUD diagnosis. Neither type of research addressed the question of how per-patient healthcare cost and service utilization changed over time among patients diagnosed with OUD. First, the astonishing trends of the total healthcare cost and clinical burdens were mainly driven by the increase in OUD prevalence and did not reflect the change in per-patient healthcare cost or healthcare resource utilization. Second, because various studies on excess healthcare cost of OUD used not only different datasets but also different criteria in defining opioid abusers and selecting corresponding control groups, results from these studies are not directly comparable and therefore are not very informative on how the excess per-patient healthcare cost or service utilization of OUD patients changed over time. In this paper, we used a large commercial claims database to estimate how per-patient excess healthcare cost changed from 2005 to 2014 among OUD patients with private insurance. In addition, we investigated how the utilization of different healthcare services, including outpatient, inpatient and ED services, changed over time in terms of the average number of visits (or hospitalization days) and the utilization rate among patients diagnosed with OUD. This is an important topic since OUD treatment is a crucial aspect of battling the epidemic. In fact, both federal and state governments have put a great amount of effort into reducing the availability and utilization barriers of OUD treatment. Availability barriers include paucity of licensed providers, capacity constraints, and stringent regulation, while utilization barriers include treatment costs and limited health insurance coverage [9, 18].

2. Methods

2.1 Data Source and Study Sample

Data used in this study are from the MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters database (MarketScan), which includes claims information from more than 130 payers, and describes the health care service use and expenditures for tens of millions per year (varying from year to year) of privately insured employees and family members. The database is divided into subsections, including inpatient claims, outpatient claims, outpatient prescription drug claims, and enrollment information. Claims data in each of the subsections contain a unique encrypted patient identifier and information on patient age, sex, geographic location (e.g., state), etc.

The MarketScan dataset used in this study covers the period from January 2005 through December 2014 for all 50 states. The demographic characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. Table 1 shows that the sample does not contain any individuals aged 65 and older, therefore, the results presented in this paper are for a privately insured non-elderly (aged 64 and younger) cohort. In addition, Table 1 shows that the demographic characteristics of included individuals remained relatively stable over this period. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to the implementation of the study.

Table 1: Demographic statistics of enrollments in the MarketScan database

Note: the percentiles in each demographic category may not sum up to 100% due to rounding errors

2.2 Study Measures and Analysis

Opioid use disorder is a diagnosis introduced in the fifth edition of theDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). It combines two disorders from the previous edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, the DSM-IV-TR, known as Opioid Dependence and Opioid Abuse, and incorporates a wide range of illicit and prescription drugs from the opioid class. Following previous studies [19, 20], we identified OUD patients for each year as those having at least one inpatient or outpatient claim with primary ICD-9 diagnosis code 304.0x (opioid type dependence), 304.7x (combinations of opioid type drug with any other drug dependence) and 305.5x (nondependent opioid abuse) in that year. Table 2 presents the number and demographic characteristics of identified OUD patients for each year. Due to varying rates of OUD prevalence among subgroups, classified by age, gender, location etc., the demographic characteristics of identified OUD patients did change over time.

Table 2: Demographic Characteristics of OUD Patients (2005 – 2014)

Note: the percentiles in each demographic category may not sum up to 100% due to rounding errors

To accommodate the change in the demographic characteristics of OUD patients over time and to study the change in healthcare cost and resource utilization for these patients, we used a matched case-control study approach. Each year, a non-OUD control group was selected from the enrollment database based on propensity score using gender, age, state, and metropolitan/non-metropolitan. Because these variables are all categorical, each year the demographic characteristics of the non-OUD control group in terms of these variables were exactly the same as that of the OUD group.

3. Results

3.1 Trends of Healthcare cost of OUD Patients

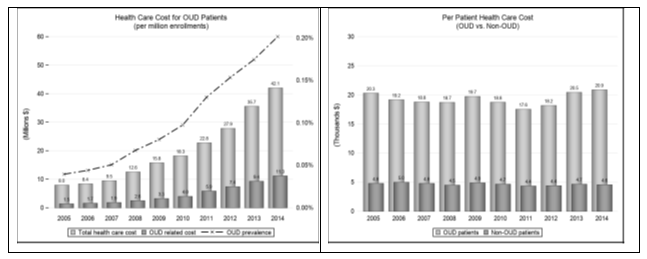

Figure 1 depicts the trends of healthcare costs, including inpatient, outpatient and drug costs, for OUD patients and the non-OUD control group. The costs were adjusted using the CPI for medical goods and services (base year: 2014) reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The left panel shows the trend of total healthcare costs for OUD patients (per million enrollments) (1). The total healthcare costs (summation of all inpatient, outpatient and drug costs) for OUD patients increased from 8.0 million dollars in 2005 to 42.1 million dollars in 2014, slightly more than a 5-fold increase. OUD-related costs (summation of healthcare costs from inpatient and outpatient claims with OUD diagnosis as the principle diagnosis and OUD-related drug (2) cost) increased from 1.5 million dollars to 11.3 million dollars during this period, more than a 7-fold increase. The OUD prevalence rate (3) increased from 0.04% to 0.20% during this period, a 5-fold increase.

The right panel of Figure 1 depicts the per-patient healthcare costs for OUD patients during this period. As a comparison, we also plotted per-patient healthcare costs for the control group. As shown, both series remained relatively stable during this period, with average per-patient healthcare costs for OUD patients being $19,265 compared to $4,679 for the control group. The average excess annual per-patient healthcare cost was $14,586. To further investigate the different components of healthcare costs for OUD patients, we plotted the trends of per-patient inpatient, outpatient, and drug costs for OUD patients in Figure 2.

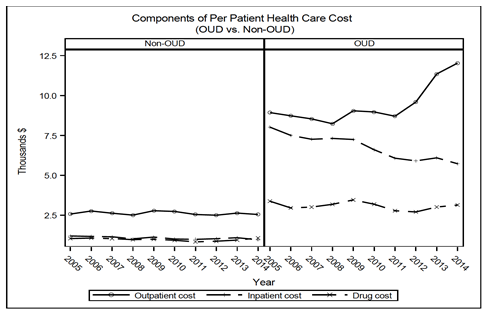

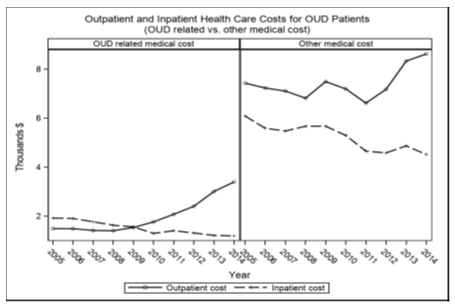

Again, the corresponding cost components for non-OUD individuals were also plotted for comparison. For OUD patients, the per-patient inpatient cost trended downward considerably from $8,017 (39.4% of the total costs) to $5,725 (27.4% of the total costs) as the per-patient outpatient cost increased considerably from $8,927 (43.9% of the total costs) to $12,027 (57.6% of the total costs) from 2005 to 2014. The per-patient drug costs remained stable, with the average per-patient drug costs being $3,083 (16.0% of the total costs). For the non-OUD group, there were no evident trends in the change of the three cost components. The annual excess per-patient inpatient cost decreased from $6,816 in 2005 to $4,763 in 2014 as the excess per-patient outpatient cost increased from $6,352 to $9,479. The excess per-patient drug cost fluctuated around $2,105. To better understand the change in outpatient and inpatient costs for OUD patients, we calculated the costs based on two categories: OUD-related costs (from claims with OUD diagnosis as the principal diagnosis) and other medical costs. As seen in Figure 3, the per-patient inpatient cost for both categories trended downward over this period. The per-patient OUD-related outpatient cost did not change much from 2005 to 2008, but increased considerably afterwards. The outpatient costs for other medical treatments varied before 2011 and experienced a rapid increase afterwards.

3.2 Trends of Healthcare Service Utilization for OUD Patients

In this section, we presented the trends of healthcare service utilization for OUD patients. In particular, we investigated inpatient, ED and outpatient care utilization for OUD patients compared to the non-OUD group.

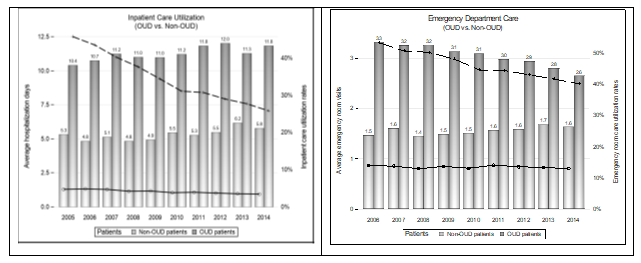

3.2.1 Inpatient Care and Emergency Department Visits

The left panel of Figure 4 shows the average hospitalization days for OUD patients (total hospitalization days / total number of OUD patients who were hospitalized at least once during that year) and the utilization rate of inpatient service (number of OUD patients who were hospitalized at least once / total number of OUD patients identified in the same year). As a comparison, we also presented the average hospitalization days and the inpatient service utilization rate for the control group. Similarly, in the right panel, we reported the average number of ED visits (total ED visits / total number of OUD patients who had at least one ED visit during that year) and the ED utilization rate (number of OUD patients who had at least one ED visit / total number of OUD patients identified in the same year).

From the left panel we can see that the inpatient care utilization rate for OUD patients decreased dramatically during this period from 45.7% in 2005 to 25.8% in 2014, but the average hospitalization days trended upward slightly, from 10.4 days in 2005 to 11.8 days in 2014 with some fluctuation between the two years. During the same period, there was a slight decrease in the inpatient care utilization rate for non-OUD individuals from 4.7% in 2005 to 3.4% in 2014. The average hospitalization stay of non-OUD patients also increased slightly from 5.3 days in 2005 to 5.7 days in 2014 with some fluctuation between the two years. The utilization rate of inpatient care dropped 19.9% (45.7% of the level in 2005) for OUD patients, compared to a 1.3% drop (27.7% of the level in 2005) for non-OUD individuals.

The right panel of Figure 4 shows the trends of ED utilization for OUD patients from 2006 to 2014 compared to non-OUD individuals (4). There was a decrease in the utilization rate of ED services, as well as in the number of per-patient ED visits for OUD patients who utilized ED services during that year. The ED service utilization rate decreased from 53.2% in 2006 to 40.0% in 2014, and per-patient ED visits decreased from 3.3 in 2006 to 2.6 in 2014. For non-OUD individuals, the utilization rate of ED services did not show any systematic change and fluctuated around its average of 13.7%. However, per-patient ED visits did increase slightly on average from 1.5 in 2006 to 1.6 in 2014 with some variation between the two years. To summarize, although OUD patients utilized substantially more ED services than non-OUD individuals, the decrease in the utilization both in terms of the utilization rate and per-patient ED visits was remarkable among OUD patients. There was no sign of a decreasing utilization rate of ED services among non-OUD individuals and the number of per-patient ED visits even experienced a slight increase during this period.

3.2.2 Outpatient care

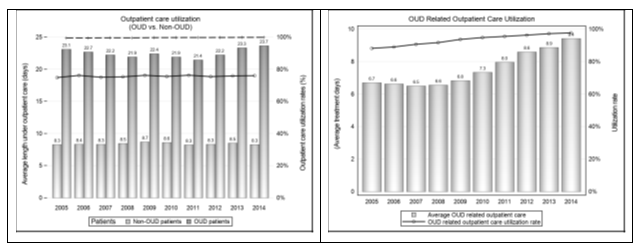

In this section, we investigated outpatient care utilization for OUD patients compared with non-OUD individuals. The outpatient care utilization rate (number of OUD patients who had at least one outpatient claim / total number of OUD patients identified in that year) and the number of per-patient outpatient visits (total number of outpatient visits/number of OUD patients who had at least one outpatient claim during that year) are presented in the left panel of

Figure 5. The corresponding measures for non-OUD individuals are also presented. From the left panel of Figure 5, we can see that the outpatient care utilization rate among OUD patients was above 99% throughout the period. This is not surprising since each year we defined OUD patients as those who had at least one inpatient or outpatient claim with an OUD diagnosis as the principal diagnosis. It is rare for OUD patients identified through inpatient claims to never have had any outpatient claims. The outpatient care utilization rate for non-OUD individuals was approximately 75%. The number of per-patient outpatient visits for OUD patients exhibited a pattern of first decreasing and then increasing with the average number of visits being 22.5, compared to 8.42 for non-OUD individuals.

To further investigate the utilization of outpatient services among OUD patients, we focused on the utilization of OUD related outpatient care in particular. We plotted the OUD related outpatient utilization rate and the number of per-patient visits in the right panel of Figure 5. The utilization rate increased from 88.1% in 2005 to 97.6% in 2014 which implies that some OUD patients identified through inpatient claims never received outpatient treatment that year, although that percentage decreased during this period. The number of per-patient visits remained stable from 2005 to 2008 and increased significantly starting in 2009. By 2014, the number of per-patient visits reached 9.4 compared to 6.7 in 2005, an increase of 2.7 or 40.6%.

4. Discussion

The total healthcare cost for OUD patients reached 42.1 million dollars in 2014, slightly more than a 5-fold increase from the total cost of 8.0 million dollars in 2005. During this sample period, the OUD prevalence rate increased from 0.04% to 0.20%, with an increasing rate similar to that of the total healthcare cost. This implies that the increase in the total healthcare cost of OUD was mainly driven by the increase in OUD prevalence, which further explains why per-patient healthcare costs for OUD patients did not change much during this period. The average excess annual per-patient healthcare cost fluctuated around an average of $14,586. It is worth noting that OUD-related healthcare costs increased at a faster rate than overall healthcare costs for OUD patients. The percentage of OUD-related costs accounted for 18.8% in 2005 compared to 26.8% in 2014 of the overall healthcare costs. This indicates that more medical resources were used for the treatment for the disease itself. However, even in 2014, a major portion (73.2%) of the healthcare costs for OUD patients were from treatment of other health problems. Therefore, reducing the risks of contracting serious OUD morbidities, such as HIV, is crucial in controlling the healthcare costs for OUD patients. A better control for the disease itself may be to potentially reduce the risk of developing morbidities.

Although the per-patient healthcare costs for OUD did not change greatly from 2005 to 2014, the distribution of the costs among outpatient, inpatient and drug utilization did change over time. The per-patient outpatient cost increased from $8,927 (43.9% of the total costs) to $12,027 (57.6% of the total costs) and the per-patient inpatient cost decreased from $8,017 (39.4% of the total costs) to $5,725 (27.4% of the total costs). This is consistent with the findings on the utilization of inpatient and outpatient services among OUD patients. The inpatient care utilization rate for OUD patients decreased dramatically during this period, from 45.7% in 2005 to 25.8% in 2014 although the average hospitalization stays among those who used inpatient services increased slightly from 10.4 days in 2005 to 11.8 days in 2014. The vast decline in the inpatient care utilization rate is likely the reason for the significant decrease in the per-patient inpatient costs for OUD patients. During the same period, there was a slight decrease in the inpatient care utilization rate for non-OUD individuals, from 4.7% in 2005 to 3.4% in 2014 and similarly, the average hospitalization length of stay slightly increased from 5.3 days in 2005 to 5.7 days in 2014. For both groups, the decrease in the inpatient care utilization rates and increase in average hospitalization days among those who used inpatient services might partially be attributed to the growing efforts on reducing unnecessary hospitalizations, greater use of chronic disease management programs, and a shift toward outpatient treatment. Those who did not need to be hospitalized were referred to outpatient services, which made the inpatient utilization rate lower. Those being hospitalized were likely to be more ill and therefore the average hospitalization stays increased.

However, this general trend toward utilizing more outpatient care might not be sufficient in explaining the dramatic drop in the inpatient care utilization rate for OUD patients. The utilization rate of inpatient care dropped 19.9% (45.7% of the level in 2005) for OUD patients, significantly more than the 1.3% decrease (27.7% of the level in 2005) for non-OUD individuals. Of course, the decline could also be caused by OUD treatment preference switching from inpatient to outpatient, for example, from inpatient rehabilitation to outpatient rehabilitation. Although we did not find evidence of such a shift in treatment preference, it could still exist. However, the fact that the per-patient inpatient costs for both treating OUD and other health problems declined (Figure 3) significantly during this period suggests that a shift in OUD treatment preference was not the only potential factor contributing to the drop even if such a shift did exist. Although the decrease in inpatient service utilization might be due to a shift toward outpatient treatment, the evident decrease in ED utilization among OUD patients (both in terms of utilization rates and average number of visits among those who utilized ED services) likely indicates better control of health conditions since ED services are usually needed to handle acute and even fatal health conditions. It is less likely to be affected by a shift in treatment preference. Moreover, this pattern did not appear in non-OUD group.

Contrary to the decrease in inpatient and ED care utilization, there was an increase in both OUD-related outpatient care utilization rates and the average number of OUD-related outpatient visits among those who received treatment through outpatient care. The increase in the average number of visits from 2009 (Figure 5) coincided with the enactment of the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA). This federal law generally prevents group health plans and health insurance providers that provide mental health or substance use disorder (MH/SUD) benefits from imposing less favorable benefit limitations on those benefits than on medical/surgical benefits [22] MHPAEA, together with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act increased access to OUD treatment and likely encouraged OUD patients to more proactively seek treatment. This could help reduce the percentage of undiagnosed OUD patients in the privately insured population. Kirson et.al found that the ratio of undiagnosed to diagnosed opioid abusers declined considerably from 2006 to 2011 among commercially insured individuals with a ratio of 2:1 in 2011 [23]. Another study found a similar trend of increasing rates of diagnosed opioid abuse cases among commercially insured individuals continuing into 2012 [14] When new OUD patients in relatively good health were diagnosed and joined the cohort, the utilization rate of inpatient care and ED services was likely to decrease. On the other hand, more proactively seeking OUD treatment could assist existing OUD patients in better managing their disease, reducing their risk of developing morbidities, and limiting their use of ED or inpatient services. Although not the primary focuses of this paper, it is worth noting that as more outpatient services and fewer inpatient and ED services were used, the indirect costs of the disease, such as workday loss from OUD patients and their family members, were likely to decrease, although the excess per-patient direct healthcare cost did not decrease (nor increase) over this period.

5. Limitations

The findings in this research are subject to the following limitations. First, the study was based on claims data from MarketScan, which is a large data set but not nationally representative. The trends in per-patient healthcare cost and service utilization presented in this paper might not reflect the corresponding trends in the privately insured population within the U.S. Additional research is needed to study the per-patient healthcare cost and service utilization in different patient populations.

Second, this study did not specifically examine the factors that caused the changes in per-patient healthcare cost and service utilization but instead focused on identifying trends in per-patient healthcare cost and service utilization among OUD patients with private insurance. The finding that an increased utilization rate of OUD-related outpatient services coincided with a decreased utilization rate in ED and inpatient services might indicate better management of the disease among OUD patients. However, other factors, such as varying demographic characteristics of OUD patients over time, might also contribute to the decrease in inpatient and ED utilization rates, although we did not see such a pattern in the control group. Further investigation on this issue would be helpful to fully understand the driving forces of these trends. Finally, like all studies based on claims data, this study was not able to capture OUD patients who never sought treatment. This is likely to render overestimation of the utilization rates for inpatient, ED and outpatient services among OUD patients with private insurance.

6. Conclusion

The increase in the total healthcare cost for OUD patients with private insurance from 2005 to 2016 was mainly driven by an increase in OUD prevalence. Excess annual per-patient healthcare costs remained relatively stable over this period. Among OUD patients, the increasing per-patient utilization of OUD related outpatient care, together with the decline in per-patient utilization of more urgent care including inpatient and ED care, might indicate increased awareness and diagnosis of OUD and better management of the disease among existing patients with private insurance. Efforts focused on reducing existing opioid treatment barriers are crucial in combating the opioid epidemic.

Footnotes

- To adjust for cross-year variation in the number of enrolled individuals in the database, the reported healthcare costs were based on one million enrollments.

- OUD-related drugs include methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone. Although these drugs could be prescribed for other addictions, such as alcohol addiction, we assumed that these drugs prescribed for OUD patients were used for OUD treatment. This was because no information was available in the dataset to identify prescribing purposes.

- Each year, OUD prevalence was defined as the total number of patients who had at least one claim on OUD treatment in that year divided by the total number of enrollments in the same year.

- The estimates on ED service utilization in 2005 were not reliable due to lots of missing values on the variable used to identify ED service. No missing values were found on this variable from 2006 to 2014. Because of this reason, we only used data between 2006 and 2014 to analyze trends of ED service utilization.

References

- Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths--United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 64 (2016): 1378-1382.

- Cicero TJ, Ellis MS. Oral and non-oral routes of administration among prescription opioid users: Pathways, decision-making and directionality. Addict Behav 86 (2018): 11-16.

- Reinhart M, Scarpati LM, Kirson NY, Patton C, Shak N, Erensen JG. The Economic Burden of Abuse of Prescription Opioids: A Systematic Literature Review from 2012 to 2017. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 16 (2018): 609-632.

- Drug Poisoning Mortality: United States, 1999-2015 (2017).

- Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65 (2016): 1445-1452.

- Prevention USCfDCa. Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2010–2015.: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2016).

- Overdose Deaths Involving Opioids, Cocaine, and Psychostimulants — United States, 2015–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 67 (2018): 10.

- Cicero TJ, Wong G, Tian Y, Lynskey M, Todorov A, Isenberg K. Co-morbidity and utilization of medical services by pain patients receiving opioid medications: data from an insurance claims database. Pain 144 (2009): 20-27.

- Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies--tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med 370 (2014): 2063-2066.

- Birnbaum HG, White AG, Reynolds JL, et al. Estimated costs of prescription opioid analgesic abuse in the United States in 2001: a societal perspective. Clin J Pain 22 (2006): 667-676.

- Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CL. Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain Med 12 (2011): 657-667.

- Meyer R, Patel AM, Rattana SK, Quock TP, Mody SH. Prescription opioid abuse: a literature review of the clinical and economic burden in the United States. Popul Health Manag 17 (2014): 372-387.

- Rice JB, Kirson NY, Shei A, et al. Estimating the costs of opioid abuse and dependence from an employer perspective: a retrospective analysis using administrative claims data. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 12 (2014): 435-446.

- Rice JB, Kirson NY, Shei A, et al. The economic burden of diagnosed opioid abuse among commercially insured individuals. Postgrad Med 126 (2014): 53-58.

- Volkow ND, McLellan TA. Curtailing diversion and abuse of opioid analgesics without jeopardizing pain treatment. JAMA 305 (2011): 1346-1347.

- Owens PL, Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Washington RE, Kronick R. Hospital Inpatient Utilization Related to Opioid Overuse Among Adults, 1993-2012: Statistical Brief #177. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD) (2006).

- Hasegawa K, Espinola JA, Brown DF, Camargo CA, Jr. Trends in U.S. emergency department visits for opioid overdose, 1993-2010. Pain Med 15 (2014): 1765-1770.

- Jones CM, Logan J, Gladden RM, Bohm MK. Vital Signs: Demographic and Substance Use Trends Among Heroin Users - United States, 2002-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 64 (2015): 719-725.

- Cochran BN, Flentje A, Heck NC, et al. Factors predicting development of opioid use disorders among individuals who receive an initial opioid prescription: mathematical modeling using a database of commercially-insured individuals. Drug Alcohol Depend 138 (2014): 202-208.

- Morgan JR, Schackman BR, Leff JA, Linas BP, Walley AY. Injectable naltrexone, oral naltrexone, and buprenorphine utilization and discontinuation among individuals treated for opioid use disorder in a United States commercially insured population. J Subst Abuse Treat 85 (2018): 90-96.

- Florence CS, Zhou C, Luo F, Xu L. The Economic Burden of Prescription Opioid Overdose, Abuse, and Dependence in the United States, 2013. Med Care 54 (2016): 901-906.

- The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA). In.

- Kirson NY, Shei A, Rice JB, et al. The Burden of Undiagnosed Opioid Abuse Among Commercially Insured Individuals. Pain Med 16 (2015): 1325-1332.

- The National Practice Guideline: For the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use In (2015).