Theories and Concepts for Human Behavior in Environmental Preservation

Article Information

Elijah A. Akintunde*

Department of Environmental Management, Institute of Life and Earth Sciences, Pan African University, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

*Corresponding Author: Elijah A. Akintunde, Department of Environmental Management, Institute of Life and Earth Sciences, Pan African University, University of Ibadan, Nigeria, Tel: +2348068241066;

Received: 31 July 2017; Accepted: 22 August 2017; Published: 30 August 2017

Share at FacebookAbstract

This paper reviews vital behavioral and environmental theories that are capable of nurturing pro-environmental citizenry. Theories are developed to explain, predict, and enhance the understanding of phenomena. Theories challenge and extend the frontiers of knowledge within the boundaries of critical bounding assumptions. Theories vary in their development on the basis of the concepts and methods employed and empirical test undertaken. The testability of a theory is one of its essential feature. An integrative application of different behavioral and environmental theories could prove to be invaluable in solving contemporary environmental problems. The models and theories reviewed in this paper include; primitive models (behavioural change model, environmentally responsible behaviour model, reasoned/responsible action theory), planned behaviour theory, environmental citizenship model, model of human interaction with the environment, the value-belief-norm theory of environmentalism, health belief theory and diffusion of innovation model. This paper concludes that none of these theories can independently entirely explain human-environment interaction, but a combination of these theories will undoubtedly provide further insights and possible solutions to the increasing 21st century environmental problems posed by humans and her technology.

Keywords

Environmental Theory, Behavioral theory, Human-Environment interaction, Environmental preservation

Environmental Theory articles Environmental Theory Research articles Environmental Theory review articles Environmental Theory PubMed articles Environmental Theory PubMed Central articles Environmental Theory 2023 articles Environmental Theory 2024 articles Environmental Theory Scopus articles Environmental Theory impact factor journals Environmental Theory Scopus journals Environmental Theory PubMed journals Environmental Theory medical journals Environmental Theory free journals Environmental Theory best journals Environmental Theory top journals Environmental Theory free medical journals Environmental Theory famous journals Environmental Theory Google Scholar indexed journals Behavioral theory articles Behavioral theory Research articles Behavioral theory review articles Behavioral theory PubMed articles Behavioral theory PubMed Central articles Behavioral theory 2023 articles Behavioral theory 2024 articles Behavioral theory Scopus articles Behavioral theory impact factor journals Behavioral theory Scopus journals Behavioral theory PubMed journals Behavioral theory medical journals Behavioral theory free journals Behavioral theory best journals Behavioral theory top journals Behavioral theory free medical journals Behavioral theory famous journals Behavioral theory Google Scholar indexed journals Human-Environment interaction articles Human-Environment interaction Research articles Human-Environment interaction review articles Human-Environment interaction PubMed articles Human-Environment interaction PubMed Central articles Human-Environment interaction 2023 articles Human-Environment interaction 2024 articles Human-Environment interaction Scopus articles Human-Environment interaction impact factor journals Human-Environment interaction Scopus journals Human-Environment interaction PubMed journals Human-Environment interaction medical journals Human-Environment interaction free journals Human-Environment interaction best journals Human-Environment interaction top journals Human-Environment interaction free medical journals Human-Environment interaction famous journals Human-Environment interaction Google Scholar indexed journals Environmental preservation articles Environmental preservation Research articles Environmental preservation review articles Environmental preservation PubMed articles Environmental preservation PubMed Central articles Environmental preservation 2023 articles Environmental preservation 2024 articles Environmental preservation Scopus articles Environmental preservation impact factor journals Environmental preservation Scopus journals Environmental preservation PubMed journals Environmental preservation medical journals Environmental preservation free journals Environmental preservation best journals Environmental preservation top journals Environmental preservation free medical journals Environmental preservation famous journals Environmental preservation Google Scholar indexed journals ERB field’s articles ERB field’s Research articles ERB field’s review articles ERB field’s PubMed articles ERB field’s PubMed Central articles ERB field’s 2023 articles ERB field’s 2024 articles ERB field’s Scopus articles ERB field’s impact factor journals ERB field’s Scopus journals ERB field’s PubMed journals ERB field’s medical journals ERB field’s free journals ERB field’s best journals ERB field’s top journals ERB field’s free medical journals ERB field’s famous journals ERB field’s Google Scholar indexed journals ecological articles ecological Research articles ecological review articles ecological PubMed articles ecological PubMed Central articles ecological 2023 articles ecological 2024 articles ecological Scopus articles ecological impact factor journals ecological Scopus journals ecological PubMed journals ecological medical journals ecological free journals ecological best journals ecological top journals ecological free medical journals ecological famous journals ecological Google Scholar indexed journals environmental variables articles environmental variables Research articles environmental variables review articles environmental variables PubMed articles environmental variables PubMed Central articles environmental variables 2023 articles environmental variables 2024 articles environmental variables Scopus articles environmental variables impact factor journals environmental variables Scopus journals environmental variables PubMed journals environmental variables medical journals environmental variables free journals environmental variables best journals environmental variables top journals environmental variables free medical journals environmental variables famous journals environmental variables Google Scholar indexed journals pro-environmental behavior articles pro-environmental behavior Research articles pro-environmental behavior review articles pro-environmental behavior PubMed articles pro-environmental behavior PubMed Central articles pro-environmental behavior 2023 articles pro-environmental behavior 2024 articles pro-environmental behavior Scopus articles pro-environmental behavior impact factor journals pro-environmental behavior Scopus journals pro-environmental behavior PubMed journals pro-environmental behavior medical journals pro-environmental behavior free journals pro-environmental behavior best journals pro-environmental behavior top journals pro-environmental behavior free medical journals pro-environmental behavior famous journals pro-environmental behavior Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

1. Introduction

For several centuries, the environment has provided habitation for humans and numerous organism but the insatiable needs of humans have driven them to devise strategies for survival and adaptation. Several of these strategies, especially technology, have had direct and indirect negative consequences on the immediate environment, resulting in the degradation of the latter. Many of today's environmental problems are increasingly the outcomes of individual actions, personal consumer decisions, and the activities of small and large businesses. Nevertheless, the fact remains that the healthiness of the world’s economy and people is inextricably bound to the wellbeing of the environment. This implies that now, much more than previously, there is a greater need to understand patterns, connections, systems and root causes of the degrading environment. A very strong tool for nipping the 21st century environmental problems, which are becoming lot more alarming in the bud, is environmental education. One veritable tool for achieving this feat is a proper understanding and the application of behavioural models and theories.

Theory is a well-established principle that has been developed to explain some aspect of the natural world. He stated further that theories arise from observations and testings that have been carried out repeatedly and they incorporate facts, predictions, laws, and tested assumptions that are widely accepted. The theoretical framework thus provides a platform for expressing a theory of a research study. It presents and describes the theory that explains why the research problem under study exists [1].

There is a close relationship between concepts and theories, such that, the constituents of a theory are concepts and principles. A concept is a symbolic depiction of an actual thing. It is the building block of the theory. The main difference between the theoretical and the conceptual framework is that a conceptual framework is the idea of the researcher on how the problem of the research will have to be explored. This is established on the theoretical framework, which lies on a much broader scale of resolution. The theoretical framework thrives that have been tested repeatedly over time that express the findings of numerous investigations on how phenomena occur. This framework provides a general representation of relationships between things in a given phenomenon. On its part, the conceptual framework describes the relationship between specific variables identified in the study. It furthermore outlines the input, process and output of an entire investigation [2]. A model is a blueprint for action, describing what happens in reality in a universal way. Models are used to describe the application of theories for a particular case. In a nutshell, theories are well-established principles developed to elucidate dimensions of the natural world, they are made up of concepts and applied by employing models.

A theory presents a systematic way of understanding behaviors, events and/or situations. It is a set of interrelated definitions, concepts, and propositions that predicts or explains events or situations by specifying relationships among the variables [3]. The notion of generality, or broad application, is important. Thus, theories are by their nature abstract and not content- or topic-specific. Although numerous theoretical models can express the same general ideas, each theory uses a unique vocabulary to articulate the specific features considered to be significant. Additionally, there is a variation in theories in the extent to which they have been developed conceptually and tested empirically. A very crucial feature of a theory is its ability to be tested [3]. Numerous theories and concepts exist for understanding Human Behaviors in Environmental Preservation. Few of these theories are reviewed below alongside their application to environmental preservation. These theories and concepts enhance further understanding as to why people participate in different environmentally influencing behaviors. It is however evident, that no single theory, gives a perfect explanation of the complete interactions and relationships among variables influencing Human Behavior in Environmental Preservation. Models and theories to be reviewed include the following; Primitive models (Behavioural change model, Environmentally Responsible Behaviour model, Reasoned/Responsible Action theory), Planned behaviour theory, Environmental Citizenship model, Model of Human Interaction with the Environment, The Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Environmentalism, Model of Diffusion of innovation and Health Belief Theory.

To properly examine the concept of Environmentally Responsible Behavior (ERB) there are 3 theories that can aid its understanding [4]. These are the Primitive models, Model of environmentally responsible behaviour proposed by Hines et al. [5] and Ajzen and Fishbein’s theory of reasoned/responsible action [6].

1.1 Primitive models

Primitive models are the traditional, ERB field’s precursors entertained beliefs that were not founded on rigorous experimentation, but rather on several assumptions interpreted from previous works [7]. These models were founded on the assumptions that educating the public on various ecological and environmental issues could alter human behaviour.

1.2 Behavioural change model

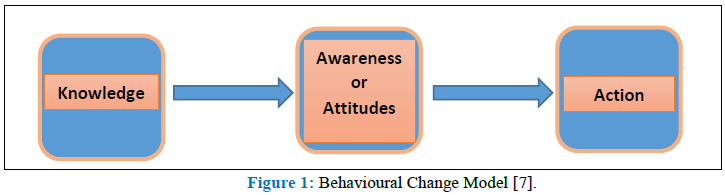

This reasoning was directly associated with the supposition that if people were better informed, they would become more aware of environmental problems and consequently, would be motivated to behave in an environmentally responsible manner. Many other similar models, as will be discussed subsequently, linked knowledge to attitudes and attitudes to behaviour. Thus, as evident in Figure 1, when knowledge increases, environmentally favourable attitudes that lead to responsible environmental actions are developed [7]. Figure 1 illustrates the relationships emanating from the models proposed at that time [4].

Nevertheless, ulterior research refuted the arguments of those that saw the principles of human behavioural change in this model. As a result of this, the legitimacy of such simplistic linear model was not recognized or supported for a long time [7]. Researchers then focused their attention on a hypothesis that they would quickly verify and accept over the course of the following years: that a multitude of variables interact in different degrees to influence the embracing of environmentally responsible behaviour.

The behavioural model, though very simplistic, provides a base for the consideration of possible relationship existing between environmental knowledge, environmental awareness and attitude and how these can translate to action or inaction. A good knowledge of environmental variables may not necessarily imply good and sustainable environmental behavior. On the other hand, lack of environmental knowledge or awareness may also not necessarily imply a poor environmental practice. Therefore other intervening factors like the Locus of control, intention to act and personal responsibility need to be considered. While a line of possible relationship can be deciphered through this model, reality is far more complex than this linear trend, hence a more advanced model, incorporating this line of relationship is needed to offer a succinct explanation of the interacting variables of human behavior in environmental preservation.

1.3 Theory of environmentally responsible behavior (ERB)

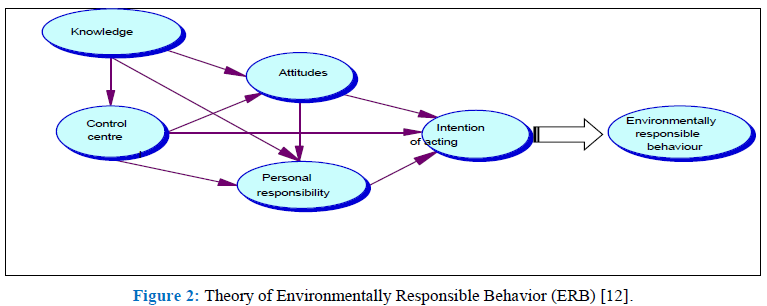

The ERB theory was proposed by Hines, Hungerford and Tomera [5]. The model argues that possessing an intention of acting is a major factor influencing ERB. The Model of Responsible Environmental Behaviorindicates that the following variables; intention to act, locus of control (an internalized sense of personal control over the events in one’s own life), attitudes, sense of personal responsibility, and knowledge .suggested whether a person would adopt a behavior or not.

Figure 2 presents the interactions likely to develop ERB. This model considers the major variables that play a part in the individual process of ERB adoption. According to the model, the internal control centre has a very considerable impact on the intention of acting, which determines an individual’s ERB substantially. This model also highlights the existence of a relationship between the control centre, attitudes of individuals and their intention to act. The authors asserted that the control centre directly affects an individual’s attitudes which can lead to an improved intention of acting and improved behaviour. Thus, the theory concentrates more on existing interactions between parameters that influence a person’s behaviour than on the singular impact of a single variable.

In waste management processes, no single factor is responsible for current behaviors or sufficient to initiate behavior or cause behavior change. For instance, people pile up their waste materials in the middle of the streets in large cities like Ibadan, Port Harcourt, Jos etc., despite regulations from waste management authorities, prohibiting these acts. Many of these flouters do so at odd hours when law enforcement agencies are not available, others are influenced to indiscriminately dump these waste materials because they see others doing so, yet some still find ways of decently disposing off their waste materials.

From the model in Figure 2, knowledge alone is grossly insufficient to act responsibly towards the environment, while some individuals’ knowledge on the environment and its regulations could prompt them to have a good attitude which could translate to good intentions to act, other individuals may go through the internal and external control, such as being influenced by the actions of others or holding strongly to a belief to act rightly despite the actions of others towards the environment. Although, separate constructs of attitudes, control center and intention of acting may not be enough for creating an intention to act, united under one overarching concept they become a base on which predispositions for pro-environmental behavior are formed.

1.4 Reasoned/Responsible action theory

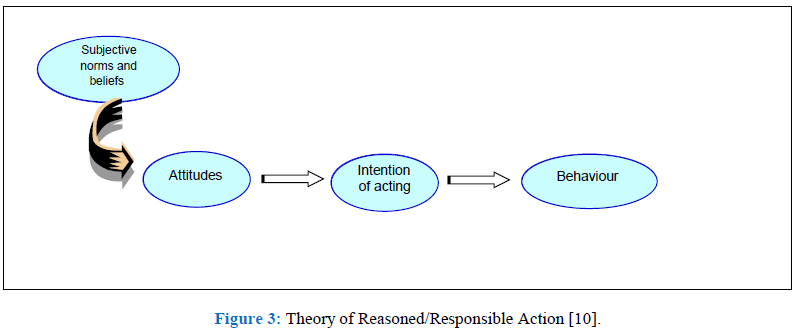

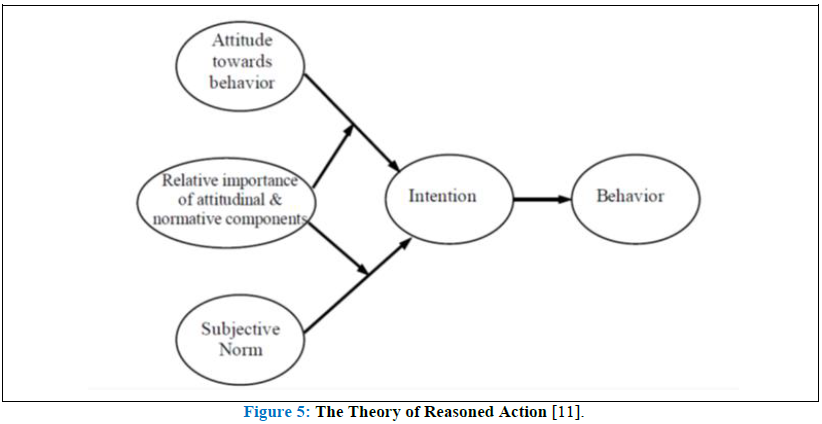

This theory was proposed by Ajzen and Fishbein [8]. The Reasoned Action Theory assumes that human behavior is grounded in rational thought, and the model uses the Principle of Compatibility, which predicts that attitudes reflect behavior only to the extent that the two refer to the same valued outcome state of being (evaluative disposition) [8]. The theory stipulates that the intention of acting has a direct effect on behaviour, and that it can be predicted by attitudes. These attitudes are shaped by subjective norms and beliefs, and situational factors influence these variables’ relative importance. Reasoned Action Theory accounts for times when people have good intentions, but translating intentions into behavior is thwarted due to lack in confidence or the feeling of lack of control over the behavior [9]. Figure 3, illustrates these relationships graphically.

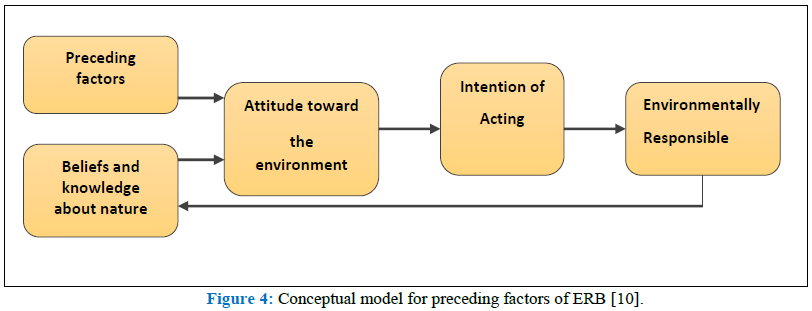

In a study published in 1995, Glenda Hanna tried to verify the coherence and validity of this Ajzen and Fishbein’s model [8]. Focusing on factors preceding the adoption of ERB, proposed a model inspired by that of Ajzen and Fishbein, the model however took the influence of previous experiences with nature into account. Shown in figure 4, preceding factors, for instance, past experience and demographic factors, interact with an individual’s knowledge and ability to act. This interaction contributes to developing environmentally favourable attitudes towards relevant issues that in turn lead to reinforcing the intention to act responsibly. Finally, these intentions are given concrete expression through the individual’s specific actions [10].

The theory of Reasoned Action is important to the extent that it provides a foundation for the understanding of why people may not act in favor of the environment, despite having good intentions either due to their lack of confidence or for the reason that they feel they lack control above the behavior. Furthermore, as asserted by Azjen and Fishbein [8], on the basis of different experiences and different normative beliefs, people may form different beliefs on the consequences of performing a behavior. These beliefs, in turn determine attitudes and subjective norms which then determine intention and the corresponding behavior. As illustrated in figure 5, better understanding of a behavior can be gained by tracing its determinants back to underlying beliefs, and thus influence the behavior by changing a adequate number of these beliefs.

The model gives further explanations as to how good intentions for the environment are not enough in themselves to propel an action. Attitudes and subjective norms, as seen in figure 5, contribute to behavioral intentions, which can be used to predict behavior. Subjective norms in this context denote an individual’s beliefs about whether their society’s members?family, friends, and co-workers?believe that the individual should or should not participate in a specific behavior. The social environment has been proven to mediate the consequence of environmental attitude on environmental behaviors [13]. Similarly, Hanna’s proposition gives a foundation for the incorporation of demographic characteristics as they influence individuals’ attitudes towards the environment, positively or negatively.

2 . Theory of Planned Behavior

The Planned Behavior Theory was proposed by [14], this model of planned environmental behavior considers the intention to act and objective situational factor as direct determinants of pro-environmental behavior. The Intention itself is considered summarizing the interplay of cognitive variables which include; (knowledge of action strategies and issues, action skills) as well as personality variables (locus of control, attitudes and personal responsibility).

The Planned Behavior Theory grew out of the Theory of Reasoned Action and it suggests that human behavior is influenced by three belief constructs: beliefs about consequences; expectations of others and things that may support or prevent behavior[15]. A strong premise of the theory is that, at the conceptual level, links among influences on behavior and their effects are captured through one of the components of the model or relationships in the model.

The application of this model to this study is that, the model provides further explanations into the connection between knowledge, attitude, behavioral intention and actual behavior as they influence waste management practices. Knowledge is not a specific component in the model but “attitudes are a function of beliefs” [8]; since in this context, beliefs refer to knowledge about a specific behavior. Azjen’s model therefore, allows for representation of cognitive elements through affective elements by their influence on beliefs. For instance, when a person understands that he/she has control over a certain situation, his/her behavioral intentions reflect this understanding as much as his/her beliefs as to the outcome of a certain behavior.

3. The Environmental Citizenship Model

This model was proposed by Hungerford and Volk [7]. The Hungerford Volk Model arrays three stages of educational involvement ranging from first exposure (entry) to real involvement (empowerment), and then suggests that each stage has certain knowledge and attitude characteristics.

In the Environmental Citizenship Model, Hungerford and Tomera grouped the variables that influence whether a person takes action into three categories, as evident in Figure 6. These are;

- Entry-level variables?such as general sensitivity to and knowledge of the environment

- Ownership variables?including in-depth knowledge, personal commitment, and resolve

- Empowerment variables?such as action skills, locus of control, and intention to act

This theory is vitally important because of its potential to evolve a citizenry that is touched with the feelings of the environment, who will bear its burdens to the extent of possessing skills that can enable them act in the interest of the environment. One popular environmental variable for instance is that of solid waste. This theory could become applicable such that whether it be purchase of goods or undertaking of services, one thing will be paramount in the minds of the citizens; sustainability of the environment. Similarly, when it comes to the generation, disposal and management of wastes; citizens will be most concerned with a sustainable manner of waste generation and management hinged on avoidance, reduction, reuse and recycling.

In application, the Hungerford Volk Model identifies numerous variables required to be an environmentally literate citizen. Secondly, the model provides a basis for the classification and separation of environmental literacy variables according to their importance either as a major variable or a minor variable. Also, the model provides a framework/scale to identify the level of an individual in the literacy ladder, such that one can tell if a citizen is in the entry level, ownership level, empowerment level or has grown to become an environmentally responsible citizen.

4. Model of Human Interaction with the Environment

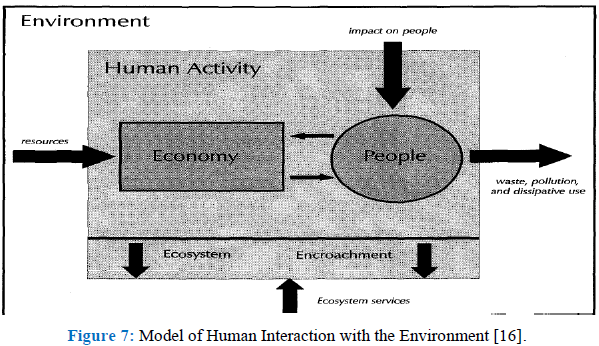

The model of human interaction with the environment was proposed by Hammond in 1995 [16]. This model describes four interactions between human activity and the environment. These are;

-

- Source: From the environment, people derive minerals, energy, food, fibers, and other natural resources of use in economic activity, thus potentially depleting these resources or degrading the biological systems (Such as soils) on which their continued production depends;

- Sink: Natural resources are transformed by industrial activity into products (such as pesticides) and energy services that are used or disseminated and ultimately discarded or dissipated, thus creating pollution and wastes that (unless recycled) flow back into the environment;

- Life support: The earth's ecosystems?especially unmanaged ecosystems?provide essential life-support services, ranging from the breakdown of organic wastes to nutrient recycling to oxygen production to the maintenance of biodiversity; as human activity expands and degrades or encroaches upon ecosystems, it can reduce the environment's ability to provide such services;

- Impact on human welfare: Polluted air and water and contaminated food affect human health and welfare directly.

This model expresses how the human activities bear imprints on the environment. While this model concerns itself with the entirety of human activities, knowledge of interacting variables in the model enhances understanding of possible outcomes for different behaviours within the environment.

5. The Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Environmentalism (Paul Stern 1999)

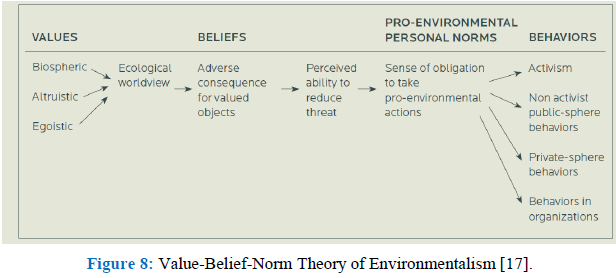

The Value Belief Norm (VBN) Theory was proposed by Stern [17]. The value-belief-norm (VBN) theory of environmentalism has its roots in some of the above theoretical accounts linking value theory, norm-activation theory, and the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) perspective through a causal chain of five variables leading to behavior: personal values (especially altruistic values), shown in figure 8. This chain of five variables, grouped into categories of values, beliefs, and norms; influences whether a person is likely to adopt some environmental behaviors.

VBN theory measures from other theories to account for three types of nonactivist environmentalism: these include environmental citizenship, private-sphere behavior, and policy support (willingness to sacrifice) [17]. The discovery was that the VBN cluster of variables was far stronger in predicting each behavioral indicator than the other theories, even when other theories were taken in combination [18]. On the VBN, behavior that will be environmentally significant is dauntingly complex, both in its variety and in the causal influences on it. Stern affirmed that, while a general theory is still yet to be arrived at, enough is known to present a framework that can increase theoretical coherence. This framework will include typologies of environmentally significant behaviors and their causes and a growing set of empirical propositions about these variables [18].

The Value Belief Norm theory, among the hitherto discussed theories, provides a more elucidative explanation of the human- environment interaction and how these interactions can affect each other, taking into consideration a relatively ample number of variables responsible for cause and action. Furthermore, the theory is well applicable to this study because:

- The Value Belief Norm approach offers a good account for the causes of the general predisposition toward pro-environmental behavior.

- Environmental practices depend on a broad range of causal factors, both general and behavior-specific. A general theory of environmentalism may therefore not be very useful for changing specific behaviors.

- Different types of environmental practices have different causes. These causal factors may vary greatly across behaviors and individuals, hence, each target behavior should be theorized separately.

In addition to the models and theories discussed above, two theories have been identified that affect environmental behavior [19]. These are the theory of diffusion of innovation and the health belief theory.

6. Diffusion of Innovation Model (Everett Rogers 1962)

In 1962, Everett Rogers introduced the concept of innovation diffusion [19]. The theory purports that change spreads in a population through a normal distribution of willingness to accept new ideas. At the level of the individual, behavioral adoption occurs through the stages of knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation and confirmation [19]. Several studies have considered and applied diffusion theory [20]. The theory was popularized with the general public in Malcolm Gladwell’s 2000 bestselling book The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. According to diffusion theory, behaviors are affected across a community through change agents. There are four elements that would affect a change agent’s own behavior while diffusing innovation and these are: involvement; social support; response information and; intrinsic control [21].

This model is important because of its ability to identify and assess the environmental literacy inducing information possessed by individuals, with respect to the content, sources, quality and effect; within a social context, social process and social support as upheld by this model.

7. Health Belief Theory

Beliefs help shape behavior. While enduring, beliefs are not fixed individual characteristics, but rather are acquired through primary socialization [22]. The Health Belief Model focuses on two aspects of an individual’s views of health and behavior. These views are threat perception and behavioral evaluation [23]. Threat perception ? or perceived risk appraisal ? is founded on one’s perceived susceptibility to illness and the anticipated severity of the consequences of such an illness. The Health Belief Model submits that, anytime there is an increase in an individual’s assessed level of risk, there is an increase in the likelihood that the individual will adopt recommended prevention behaviors [24]. Behavioral evaluation, also known as coping appraisal [25] relates to the belief that an available course of action will be beneficial and the anticipated barriers or costs of embarking on an action do not outweigh the benefits [26]. In addition to these core components of the model, there are demographic, socio-psychological and structural variables, as well as ‘cues to action’ [24]. Cues to action are the stimuli necessary to initiate or trigger engagement in the desired, healthy actions. Cues could come in the form of media campaigns or the illness of a family member, relative or close friend [27].

The Health Belief Model has been extensively used in health education to predict behavior change and research continues to reveal validity in the model. Over time, much of the work of environmental and conservation education has been framed to address the four core components of the Health Belief Model [19]. The concepts of issue relevance and cues to action, for example, are prevalent in the Guidelines for Excellence of the National Project for Excellence in Environmental Education. Therefore, making the concepts explicit and focusing on the secondary variables may benefit environmental education [19].

Tenets of this theory could be applied in environmental studies for prediction of behavior change, particularly a study like this one which also bears an interplay with health in terms of some negative environmental practices that can lead to the incidence/prevalence of diseases. Also, the Health Belief Theory will enable the researcher to assert if the fear of negative outcomes from bad environmental practices will propel individuals to imbibe pro-environmental practices or not. Furthermore, since pro-environmental behavior is a mixture of self-interest (e.g., pursuing a strategy that minimizes one’s own health risk) and of concern for other people, the next generation, other species, or whole ecosystems (e.g. preventing air pollution that may cause risks for others’ health and/or the global climate), this model can as such provide a good base for a better understanding for such cause and action.

The discourse of environmental education and waste management cuts across numerous areas especially for the reason that it deals with human behavior which is in itself a complex variable. Hence several concepts, models and theories have evolved over the years to attempt an explanation into this interaction.

In conclusion, an amalgamation of these models and theories can create relational paths to finding long lasting solutions to various environmental problems created by different human behaviors. For instance, the Environmental Citizenship Model (ECM), the Value Belief Norm theory and the Reasoned Action Theory could be integrated in a way that the Environmental Citizenship model provides a framework/scale to identify the level of an individual in the environmentally literacy ladder. The ECM can help determine if a citizen is in the environmental entry level, ownership level, and empowerment level; along with the likely environmental behavior a citizen would demonstrate. The ECM is insufficient since it makes no provision for the biospheric, altruistic and egoistic values of the individual, thus, the Value Belief Norm theory (VBN) can be complementary to the ECM. Furthermore, the VBN specifies the kind of pro environmental behavior, be it activism, non-activist public sphere behavior, private sphere behavior and behaviors in communities, which are not emphasized in the ECM. The Reasoned Action Theory complements the ECM and VBN by providing a better understanding that good intentions towards the environment are not enough in themselves to propel an action. It further explains that attitudes and subjective norms, contribute to behavioral intentions, which can be used to predict behavior. The models and theories reviewed will undoubtedly prove invaluable in the quest for nurturing a citizenry who will engage the environment sustainably.

8. Acknowledgement

Warm gratitude to the African Union Commission for its support for this paper through The Pan African University, (Institute of Life and Earth Sciences, Nigeria) scholarship. I thank Prof. S.B Agbola and Dr.W.B. Wahab for their supervision, I also thank the editor and the reviewers.

References

- Swanson RA, Chermack TJ. Theory building in applied disciplines. Berrett-Koehler Publishers (2013).

- Regoniel P. What is the Difference between the Theoretical and the Conceptual Framework? (2013).

- NIH: Esource National Institute of Health. Social and Behavioral Theories. (2015).

- Boudreau G. Behavioural change in environmental education. (2010).

- Hines JM, Hungerford HR, Tomera AN. Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behavior: A meta-analysis. The Journal of environmental education 18 (1987): 1-8.

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M.Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. (1980).

- Hungerford HR, Volk TL. Changing learner behavior through environmental education. The journal of environmental education 21 (1990): 8-21.

- Schifter DE, Ajzen I. Intention, perceived control, and weight loss: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49 (1985): 843-851.

- Hanna G. Wilderness-related environmental outcomes of adventure and ecology education programming. The Journal of Environmental Education 27 (1995): 21-32.

- Kibert NC. An Analysis of the Correlations between the Attitude, Behaviour, and Knowledge Components of Environmental Literacy in Undergraduate University Students. Unpublished Dissertation the University of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science University of Florida, Florida (2000).

- Stern PC, Dietz T, Abel T, et al. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Human Ecology Review 6 (1999): 81-97.

- Peggy P, Korsching PF. Farmers’ attitudes and behaviour toward sustainable agriculture. Journal of Environmental Education 28 (1996): 38-45.

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes. 50 (1991): 179-211.

- Ajzen I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior, Journal of Applied Social Psychology 32 (2002): 665-683.

- Hammond A, Adriaanse A, Rodenburg E, et al. Environmental Indicators: A Systematic Approach to Measuring and Reporting on Environmental Policy Performance in the Context of Sustainable Development. World Resources Institute (1995).

- Stern PC. Information, incentives, and proenvironmental consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Policy 22 (1999): 461-478.

- Stern PC. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues 56 (2000): 407-424.

- Heimlich JE, Ardoin NM. Understanding behaviour to understand behaviour change: a literature review, Environmental Education Research 14 (2008): 215-237.

- Rogers EM, Shoemaker FF. Communication of innovations; A cross-cultural approach (Revised edition of Diffusion of Innovations). New York: Free Press of Glencoe (1971).

- Geller ES, Berry TD, Ludwig TD, et al. A conceptual framework for developing and evaluating behaviour change interventions for injury control. Health Education Research: Theory and Practice 5 (1990): 125-137.

- Sheeran P, Abraham C. The Health Belief Model. In Predicting health behaviour: Research and practice with social cognition model. Conner M, Norman P, Buckingham, UK: Open University Press (1996): 23-61.

- Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly 11 (1984): 1-47.

- Mattson M. Toward a reconceptualization of communication cues to action in the Health Belief Model: HIV test counselling. Communication Monographs 3 (1999): 240-265.

- Zak-Pace J, Stern M. Health belief factors and dispositional optimism as predictors of STD and HIV preventive behaviour. Journal of American College Health 52 (2004): 229-236.

- Rosenstock IM, Glanz KG, Lewis FM, et al. The Health Belief Model: Explaining health behaviour through expectancies. In Health behaviour and health education (1990): 39-62.

- Winfield EB, Whaley AL. A comprehensive test of the Health Belief Model in the prediction of condom use among African American college students. Journal of Black Psychology 28 (2002): 330-346.

- Woodell J, Garofoli E. Faculty development and the diffusion of innovations. Campus Technology (2002).