The Necessity of Maternal Acquaintances and Learnings Towards Complementary Feeding to Prevent and Manage the Major Micronutrient Deficiencies for Under Five Children in Bangladesh

Article Information

Mohammed Reaz Mobarak1*, Rafiqul Islam2, Fazlul Haque3, Shah Mohammed Masuduzzaman4, Mohammed Kamruzzaman5, Md. Nurunnabi6, Tonmoy Karmokar7

1High Dependency and Isolation Unit, and Epidemiology and Research, Bangladesh Shishu Hospital and Institute, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2High Dependency and Isolation Unit, and Epidemiology and Research, Bangladesh Shishu Hospital and Institute, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3Department of Peadiatrics, Maa O Shishu Hospital, Mirpur, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4Department of Paediatrics, Sheikh Hasina Medical College & Hospital, Tangail, Bangladesh

5Department of Paediatrics, Community Based Medical College, Mymensingh, Bangladesh

6Department of Pediatrics, Union Specialized Hospital, Mymensingh, Chamber Preety Medical Hall, Sherpur, Bangladesh

7Department of Paediatrics & Neonatology, Tairunnessa Memorial Medical College & Hospital, Gazipur, Bangladesh

*Corresponding Author: Mohammed Reaz Mobarak, Professor & Head of the Department, High Dependency and Isolation Unit, and Epidemiology and Research, Bangladesh Shishu Hospital and Institute, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Received: 06 October 2022; Accepted: 03 November 2022; Published: 23 January 2023

Citation: Mohammed Reaz Mobarak, Rafiqul Islam, Fazlul Haque, Shah Mohammed Masuduzzaman, Mohammed Kamruzzaman, Md. Nurunnabi, Tonmoy Karmokar. The Necessity of Maternal Acquaintances and Learnings Towards Complementary Feeding to Prevent and Manage the Major Micronutrient Deficiencies for Under Five Children in Bangladesh. Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Research 6 (2023): 07-16.

Share at FacebookAbstract

When most infants reach a general and neurological stage of development (chewing, swallowing, digestion, and excretion), the target age range for complementary feeding is between the ages of 6 and 23 months (while breastfeeding is continued). At this point, they are able to be fed other foods instead of breast milk in order to fill the gaps between an infant's and young child's daily energy and nutrient requirements and the amount obtained from breastfeeding, complementary foods may be specifically designed transitional foods (to meet specific nutritional or physiological needs of infants) or general family foods. The undernutrition of children may be reduced with the help of health workers who have undergone nutrition training. By improving child feeding practices, the risk of undernutrition in children of recommended caregivers may be reduced. Infants and young children are at an increased risk of malnutrition from six months of age on, when breast milk alone is no longer sufficient to meet all of their nutritional demands and supplemented feeding should be started. The first two years of life require proper nutrition in order for everyone to reach their full potential. The importance of this time period for promoting healthy development, growth, and development is still recognized today. Thus, adequate eating affects children's health, nutritional status, growth, and development during this stage of life not just in the short term but also in the medium and long terms. This paper provides complementary feeding (CF) recommendations that are presented as questions or statements for those who are responsible for caring for children throughout this time of life. Examples include knowing when to offer complementary feedings, introducing meals in the correct order, and taking into account how foods vary in consistency as a child's nervous system develops. Quantities for each meal, poor complementary feeding techniques, myth

Keywords

Complementary feeding, Breastfeeding practices, Healthy infants, Guidelines

Complementary feeding articles; Breastfeeding practices articles; Healthy infants articles; Guidelines articles

Complementary feeding articles Complementary feeding Research articles Complementary feeding review articles Complementary feeding PubMed articles Complementary feeding PubMed Central articles Complementary feeding 2023 articles Complementary feeding 2024 articles Complementary feeding Scopus articles Complementary feeding impact factor journals Complementary feeding Scopus journals Complementary feeding PubMed journals Complementary feeding medical journals Complementary feeding free journals Complementary feeding best journals Complementary feeding top journals Complementary feeding free medical journals Complementary feeding famous journals Complementary feeding Google Scholar indexed journals Breastfeeding practices articles Breastfeeding practices Research articles Breastfeeding practices review articles Breastfeeding practices PubMed articles Breastfeeding practices PubMed Central articles Breastfeeding practices 2023 articles Breastfeeding practices 2024 articles Breastfeeding practices Scopus articles Breastfeeding practices impact factor journals Breastfeeding practices Scopus journals Breastfeeding practices PubMed journals Breastfeeding practices medical journals Breastfeeding practices free journals Breastfeeding practices best journals Breastfeeding practices top journals Breastfeeding practices free medical journals Breastfeeding practices famous journals Breastfeeding practices Google Scholar indexed journals Healthy infants articles Healthy infants Research articles Healthy infants review articles Healthy infants PubMed articles Healthy infants PubMed Central articles Healthy infants 2023 articles Healthy infants 2024 articles Healthy infants Scopus articles Healthy infants impact factor journals Healthy infants Scopus journals Healthy infants PubMed journals Healthy infants medical journals Healthy infants free journals Healthy infants best journals Healthy infants top journals Healthy infants free medical journals Healthy infants famous journals Healthy infants Google Scholar indexed journals Guidelines articles Guidelines Research articles Guidelines review articles Guidelines PubMed articles Guidelines PubMed Central articles Guidelines 2023 articles Guidelines 2024 articles Guidelines Scopus articles Guidelines impact factor journals Guidelines Scopus journals Guidelines PubMed journals Guidelines medical journals Guidelines free journals Guidelines best journals Guidelines top journals Guidelines free medical journals Guidelines famous journals Guidelines Google Scholar indexed journals undernutrition articles undernutrition Research articles undernutrition review articles undernutrition PubMed articles undernutrition PubMed Central articles undernutrition 2023 articles undernutrition 2024 articles undernutrition Scopus articles undernutrition impact factor journals undernutrition Scopus journals undernutrition PubMed journals undernutrition medical journals undernutrition free journals undernutrition best journals undernutrition top journals undernutrition free medical journals undernutrition famous journals undernutrition Google Scholar indexed journals food insecurity articles food insecurity Research articles food insecurity review articles food insecurity PubMed articles food insecurity PubMed Central articles food insecurity 2023 articles food insecurity 2024 articles food insecurity Scopus articles food insecurity impact factor journals food insecurity Scopus journals food insecurity PubMed journals food insecurity medical journals food insecurity free journals food insecurity best journals food insecurity top journals food insecurity free medical journals food insecurity famous journals food insecurity Google Scholar indexed journals nutrition status articles nutrition status Research articles nutrition status review articles nutrition status PubMed articles nutrition status PubMed Central articles nutrition status 2023 articles nutrition status 2024 articles nutrition status Scopus articles nutrition status impact factor journals nutrition status Scopus journals nutrition status PubMed journals nutrition status medical journals nutrition status free journals nutrition status best journals nutrition status top journals nutrition status free medical journals nutrition status famous journals nutrition status Google Scholar indexed journals micronutrient deficits articles micronutrient deficits Research articles micronutrient deficits review articles micronutrient deficits PubMed articles micronutrient deficits PubMed Central articles micronutrient deficits 2023 articles micronutrient deficits 2024 articles micronutrient deficits Scopus articles micronutrient deficits impact factor journals micronutrient deficits Scopus journals micronutrient deficits PubMed journals micronutrient deficits medical journals micronutrient deficits free journals micronutrient deficits best journals micronutrient deficits top journals micronutrient deficits free medical journals micronutrient deficits famous journals micronutrient deficits Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

Introduction

For 45% of all child fatalities, undernutrition, including stunting and inadequate breastfeeding, is to blame. According to estimates, 70% of the world's stunted children live in Asia, with Bangladesh having the second-highest rate of child undernutrition [1,2]. The WHO defines complementary feeding as "the process that starts when breast milk alone is no longer sufficient to fulfill the nutritional needs of neonates, and extra meals and liquids are thereafter required, in addition to breast milk" [3]. Therefore, the purpose of complementary feeding is to facilitate the gradual switch from family-wide ingestion of solid foods together with breastfeeding to exclusively breastfeeding for six to 24 months. Poor CFP has been linked to an increased risk of respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses as well as mortality [4,5]. Only 71% of Bangladeshi babies consume the recommended supplementary foods, and once CF develops, many of them "fall off the growth curve”, by the time they are 6 to 8 months old [6]. Therefore, it's imperative that the WHO's recommendations for treating CF are widely adopted [7]. For effective CF, caregivers must employ suitable nutritional knowledge and ensure that there is enough food available in the home [8]. While BF approaches have been the focus of several studies, CF has gotten less consideration. According to the 2010 WHO Infant and Young Children Feeding (IYCF) guidelines, a globally acknowledged framework put into practice in Bangladesh [9] infants should be breastfed exclusively throughout the first six months of life in order to achieve optimal growth, development, and health. Babies should thereafter be provided safe and nutritionally enough supplemental meals if breastfeeding is continued for an additional two years or longer. Undernutrition is particularly prevalent in low- and lower-middle-income countries and is to blame for more than one-third of all child mortality globally [1]. Poverty has continued to have a big impact on how poorly nourished children are in these places [3,4]. It has been cited as a cause of poor child nutrition status, which is linked to food insecurity [5,6], low maternal education [7,8], inconsistent access to healthcare [7,8], and the burden of sickness [8]. The financial disadvantage of caregivers may also have an impact on their poor feeding practices toward their young charges [9,10]. Poor feeding behaviors include eating infrequently, providing little diversity in the diet, and consuming too many calories [11-13]. Social problems such caregivers' lack of nutrition education and understanding of the diversity of foods accessible in their environment may be linked to poor eating habits [14]. Children may consume less food overall, less often, and with less diversity in their diets as a result of these factors. Caregiver nutrition education may improve their general awareness of nutrition and help debunk cultural and traditional myths [15]. Therefore, if patients are treated, given guidance on proper eating procedures, and have their progress periodically monitored, food habits may be improved [16]. Naturally, dieticians and nutritionists may offer this sort of guidance when they are available [17-19]. However, in many developing countries, there may not be sufficient medical practitioners with these specialized skills to offer routine care [20,21], therefore these services are instead provided by medical professionals with just a general grasp of nutrition. According to the evidence that is currently available, changing eating habits may help health practitioners who get nutrition training decrease child undernourishment. Prior randomized controlled trials (RCTs) among health professionals who had received nutrition training revealed higher levels of nutrition knowledge and counseling behavior [22,23]. Their understanding of nutrition also enhanced when caregivers often sought guidance from medical specialists who had received nutrition training [16]. Nutrition counseling also improved the understanding of caregivers on proper feeding procedures and food preparation [24,25]. Increases in feeding frequency [26], dietary diversity [19], protein consumption [24], and calorie intake [20] were also more common among caregivers. These feeding techniques must be used if we want to enhance children's nutritional status [21,27]. There may be potential for ongoing nutritional counseling within the present health care systems. While 88 percent of pregnant women globally received at least one prenatal visit in 2012, just 50% of new mothers attended a medical facility after giving birth [22]. These prospective options present opportunities for competent medical experts to offer nutritional advice. Only 57% of mothers had a skilled attendant present when their babies were delivered [28]. However, there is also a role for at-home dietary advice for these women from peers or local health professionals who have the required education and experience.

Complementary Feeding

The future of infants and children as well as the expansion of the society they live in depend on maintaining optimal growth and development [29]. As a result of poor feeding habits, such as the discontinuation of exclusive breastfeeding and the early introduction of weaning foods, children may experience malnutrition. Major contributing factors include poor nutrition later in infancy [27]. Studies have connected household food insecurity to the likelihood of stunting and underweight in preschoolers, as well as detrimental consequences on development and learning ability [27,28]. Security in the home's food supply has also been linked to children's greater development. 14 Children between the ages of 6 and 24 months are frequently the target of complementary/supplementary food therapy since young children are most likely to have developmental issues, micronutrient deficits, and infectious diseases [7]. The preschool years (ages 1-4) represent a period of significant and fast postnatal brain development (sometimes referred to as neural plasticity), as well as the formation of fundamental cognitive abilities (i.e., working memory, attention, and inhibitory control). Programs that concentrate on specific nutritional deficits might not be as effective or long-lasting as a food-based, all-encompassing strategy. Moms must make difficult choices regarding when and how to start supplementary feeding since there are numerous factors that might impact it. Understanding the decision-making process, social beliefs, knowledge, attitude, and supplementary feeding practices is essential before devising an intervention strategy to prevent childhood malnutrition. Poor eating habits, including breastfeeding and supplementary feeding, as well as a lot of infectious diseases are the main proximal causes of malnutrition in the first two years of life. A child's optimal IYCF protects them from both under- and over-nutrition as well as the long-term repercussions of either. Breastfeeding is a low-cost treatment for obesity, according to reviews of several research [19,20]. Breastfed infants had a lower risk of acquiring asthma, diabetes, heart disease, high cholesterol, and other cardiac risk factors compared to newborns who were artificially fed, as well as malignancies including childhood leukemia [16] and breast cancer later in life [17]. Given the significant link between poor food quality and obesity, effective supplemental feeding may help people stay underweight and obese by providing a variety of nutrient-dense meals. For nations that are going through a nutrition transition and are dealing with a double burden of malnutrition, it is even more important to make sure that investments are made in children under the age of two to lower the risk of stunting and obesity (both under and over-nutrition). Rapid weight increase during the first two years is necessary for neonates were previously underdeveloped in order to prevent long-term undernutrition and lower morbidity and death. Rapid weight growth in later childhood is not ideal if a kid is unable to catch up before the age of two since it considerably raises the risk of chronic illness. The worst-case scenario for chronic illnesses, such as cardiovascular and metabolic issues, is a low birth weight infant who is stunted and underweight throughout childhood and adulthood before becoming overweight.

Figure 1:

It is very much important for the baby to introduce the Complementary Feeding to meet the followings

Physiological & Nutritional Demand

- Breast milk is sufficient to promote growth and development only till 6 months of baby age [1]

- Energy and nutrient gap appears after 6 months and widens thereafter [2]

- Malnutrition is responsible, directly or indirectly, for over half of all childhood deaths [3]

- 45% of child deaths is associated with undernutrition.

Behavioral & Developmental Demand

- Holds objects and takes everything to mouth

- Chewing movements start

- Tendency to push solids out decreases

- Eruption of teeth and beginning of biting movements

- Opens mouth and shows interest when others eat

- Receives frequent breast feed but appears hungry soon

- Not gaining weight adequately

Beliefs regarding Complementary feeding

Previous research [21] shown that only 50% of mothers were aware that the best time to start complementary foods is when a baby is 6 months old. Contrarily, moms said that one-fourth of them thought that complementary foods should be offered before the baby is six months old. In Ethiopia, it was shown that 19.7% of moms began supplemental feeding before the child became six months old [4]. More than three-quarters of the mothers in the present study were aware of various supplemental meal types, in accordance with the findings of other studies [30]. All moms in Finland [21,22] agreed that supplementary meals are beneficial for kids. The important views that mothers hold about the advantages and disadvantages of introducing supplemental feeding, as well as the value of other people's opinions, are the elements that have the most effect on mothers' decisions about complementary feeding. According to a different study, mothers' decisions were significantly impacted by their perceptions of the advantages of supplemental feeding as well as those of their neighbors, family members, and health care providers [22]. The majority of mothers hold the opinion that complementary meals are beneficial for their children in a variety of ways, including by promoting brain development in infants and giving them extra nutrition for normal growth and development and better intelligence. This finding is at odds with that of an Australian study, which found that some mothers did not see the initiation of supplementary feeding as beneficial [30]. According to the most recent study, mothers who want to reduce the frequency of breastfeeding and feel free to work without worrying about their child's hunger add supplements to their children's meals. But practically all mothers said that their babies dislike eating anything. In line with studies showing that the majority of youngsters exclusively drank breast milk for nourishment [22,30]. Few mothers make an effort to play-feed their newborns, and more than half force-feed their kids. The mothers could not have been well educated, and it's possible that they were unaware of how to feed themselves or the dangers of forced eating. According to a study, moms have an inaccurate understanding about complementary feeding. For instance, many think that supplementary meals are to blame for their children's illnesses and avoid providing them to them [12]. The vast majority of the women sought advice from their family about supplementary feeding. This outcome is consistent with the findings of [21] study, which showed that fathers had an impact on infant and young child eating behaviors. However, other studies showed that women found information on their own from sources including friends, family, the neighborhood, radio, television, and medical facilities. The mothers of the children may have all been housewives and residents in slum neighborhoods, which may have been the reason. Consequently, it was difficult to step outside and approach the medical staff for advice.

Period of Complementary Feeding

Up to the age of six months, a child can only get its nutrition from breastmilk; after that point, supplementary feeding must begin. At five months, the jaw also begins to move in a biting action. At about 6-7 months, swallowing of solid foods begins. The tongue starts to move side to side between the ages of 8 and 12 months. The "sensitive phase" or best time to initiate supplementary feeding is about six months. Delayed supplementary feeding may lead the child to enter a "critical period," after which the child may constantly have difficulty chewing and may struggle to eat solids in the future.

Additional advantages of supplemental feeding at six months of age include the following:

- Child gains better neck/head control and hand-to-mouth coordination.

- The intestines are matured and ready to process grains and pulses. The child starts to enjoy biting and mouthing.

- The infant likes chewing and gumming semisolids because of gum hardening and tooth emergence.

- It's less likely to push food out of the mouth when it's solid.

The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that newborns nurse exclusively for the first six months, then continue to do so while consuming supplementary meals until they are two years old or older. The shift from family meals to nursing alone, also known as supplementary feeding.

- Typically, complementary feeding is provided to infants between the ages of 6 and 24 months.

- Despite the fact that nursing may continue until the age of two.

Appropriate complementary feeding

After six months, a baby's nutritional and energy requirements start to outpace those of breast milk, necessitating the consumption of supplemental meals. At this age, a baby is also developmentally prepared to eat other foods. Complementary feeding is the term used to describe this shift.

An infant's growth may stall if supplementary meals are not offered at the age of 6 months or if they are introduced improperly.

- When the requirement for energy and nutrients is more than what can be met by exclusive and frequent nursing, meals are introduced in a timely manner;

- Adequate in terms of calories, protein, and micronutrients to support the nutritional demands of a growing youngster;

- Safe means that food is hygienically produced, stored, and fed, and that clean utensils are used to feed instead of bottles and teats;

- When a kid is properly fed, meals are provided in accordance with their signals of hunger and fullness, and meal times and feeding techniques, such as actively encouraging them to use their fingers, a spoon, or self-feeding, are acceptable for their age.

|

Appropriate |

Avoidable |

|

Combination of cereals and pulses (Khichdi, Dal-rice, etc.), locally available staple foods such as idli, dosa, dhokla, ragi, chapati, roti, paratha with oil/ ghee, and some amount of sugar. |

Biscuits, breads, pastry, chocolates, cheese, softy, ice cream, doughnuts, cakes, etc. Tinned foods, packaged or stored foods, artificially cooked foods with preservatives or chemicals |

|

Mashed banana, other pulpy fruits (e.g., mango, papaya), sweet potato, and potato |

Fruit juices and fruit drink |

|

Milk-based cereals preparations |

Commercial breakfast cereals |

|

Sprouts, pulses, legumes, groundnuts, almonds, cashewnuts, raisins (Note: Any nut should be well grinded and mixed with food as solid pieces maycause choking in young children) |

Repeatedly fried foods containing trans-fatty-acids (which predispose to obesity, diabetes, atherosclerosis, cardiac, and neurological problems in future) |

Table 1: Categorizes the appropriateness of complementary foods for infants

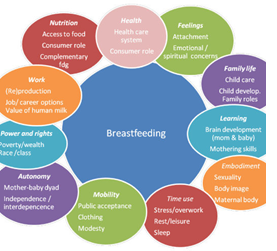

Breastfeeding practice

Due to its effect on morbidity and mortality, particularly in young children under 1-year-old, breastfeeding is a crucial component of a child's nutrition and has significant consequences for the welfare of human health. Over this, organizations concerned with infant health have come to understand the importance of breast milk as the child's preferred food during the first six months of life, and it is viewed as a crucial public health policy. The World Health Organization (WHO) advises exclusively nursing a newborn for the first six months of their life, beginning as soon as possible after birth [18]. The WHO has set the 2025 Global Nutrition Targets in order to enhance the nutrition of expectant mothers, newborns, and young children. Breastfeeding is prioritized in the fifth of these, "increase the percentage of exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months up to at least 50%." The three main sociodemographic factors that impact breastfeeding duration are age, marital status, and socioeconomic status. Younger women with low levels of education, unmarried women, and women with lesser incomes therefore had a decreased probability of effectively continuing nursing for a long period [12]. A recent study [13] found that factors with high effects included smoking, birth mode, parity, mother-child separation, maternal education, and maternal education on breastfeeding. For instance, breastfeeding rates at 6 months were much higher for women who had completed high school or other higher education programs, had access to breastfeeding information, began nursing right away after giving birth, and did not work. But among women who smoked and lived at home with their parents, the rate of breastfeeding for the first six months was much lower [29]. Teenagers breastfeed less often and for a shorter amount of time than adults [27]. and breastfeeding duration is strongly connected with maternal age. Adolescent mothers assert that the decision to breastfeed is decided prior to childbirth and that their partner's and family members' attitudes about the practice may affect when it starts. Several elements influence nursing, including its effects on social and personal connections, the availability of social support, the physical challenges of breastfeeding, comprehension of breastfeeding practices and their benefits, and the mother's degree of comfort with breastfeeding. [28]. If parents in this age group have a better prenatal attitude about starting breastfeeding and stronger confidence in pre and postnatal care, they are substantially more likely to continue nursing 4 weeks after giving birth [14]. In this way, nursing behavior is complicated. In addition to sociodemographic, clinical, and behavioral factors, each woman's decision to start breastfeeding and ability to do so are impacted by a range of social, psychological, and cultural factors as well. These effects work at several levels, from the individual to society.

All the variables that affect nursing practice's growth and the many levels that interact must be taken into account when creating a conceptual model of it. It is feasible to understand how several levels interact and affect a person's choice to breastfeed or not.

Vital source of energy (30-40%) and nutrients into 2nd year of life [1]

- Key source of-

- Good quality proteins & essential fatty acids

- Micronutrients:

- 45% of Vitamin A

- 40% of calcium & riboflavin

- 95% of Vitamin C

- Fluids and nutrients during infection

- Associated with greater linear growth

- Linked to lower risk of chronic diseases & obesity

Complementary feeding Practices in Bangladesh

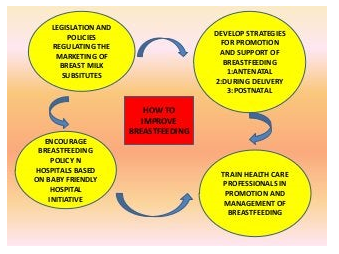

Bangladesh faces several challenges while trying to feed growing children nutritious food. Bangladesh must overcome a number of challenges to give growing children age-appropriate nutrition in order to prevent undernutrition throughout the early stages of development [11]. A kid should only be fed breast milk for the first six months to provide appropriate nourishment and the growth of a strong immune system. Parents are required to continue breastfeeding their children until they are two years old beyond this point and to start include some meals in their diets. This strategy [29], known as complementary feeding, facilitates the transition from exclusively nursing to family meals. It is necessary for giving a child the additional nutrition they require and covers the crucial 6-24-month period for their physical and mental development. Due to dietary deficiencies and illnesses, there are more cases of undernutrition among children under the age of five worldwide at this time. When it comes to adding food to their children's meals, many parents lack the fundamental understanding about the optimum times to start, how frequently, and the absolute minimum needs for nutritional diversity. There is food insecurity in the household for one-fourth of the population [31]. Families on tight finances may not always be able to afford proteins like beef and fish. In many areas of the country, especially urban slums, the rates of age-appropriate supplementary feeding are alarmingly low. In Bangladesh, mothers frequently choose for formula and may struggle to convince their husbands to buy meat and fish. In certain communities, it considered folklore to give children meat and fish. Although young children are frequently not given these items, they are occasionally easily available at home. Breastfeeding must start within an hour of delivery in order to guarantee that babies receive colostrum, often known as "first milk," which is rich in nutrients necessary for protecting newborns against common ailments including pneumonia and diarrhea. Few families practice this early starting and nursing for up to two years due to variances in geographic location and socioeconomic background. For instance, the early starting rate in Sylhet is 73.5% whereas it is 47.3% in Khulna Division [12]. Breastfeeding rates are lower for mothers from the poorest and richest quintiles, at 48.1 and 62.5 percent, respectively. Although Bangladesh has achieved the exclusive breastfeeding target set by the World Health Assembly, there has been a concerning decline in the practice. UNICEF works with the government to train medical staff members in counseling methods and to enhance their communication skills [5]. These community-based specialists demonstrate unique methods for making sure children, families, and caregivers are fed. The government also instructs medical personnel on how to properly breastfeed, how to preserve breastmilk, how to cure disorders of the breast, and how to handle apparent milk shortages. Additionally, evaluation and analysis of household habits are taught to health professionals, who then use the findings to develop efforts focused on change. UNICEF also works with medical facilities to compile monthly statistics on all district-level nutrition standards. UNICEF works with the government to create guidelines for supplementary foods for kids, including those for amount, variety, frequency depending on age, texture, and cleanliness. Some examples are boiled vegetables, animal protein, mashed cereals, and ripe fruits like papaya and mango. UNICEF is aggressively working to raise the proportion of mothers who receive nutrition advice as part of prenatal care. We are focusing on raising the proportion of caregivers who receive nutrition advice overall, along with improving the accessibility of vitamin A effort for children between the ages of 6 months and 5 years. As part of our efforts to address the expanding needs of women and children in urban areas, UNICEF promotes the rights of women and children in the workplace. By establishing the 7 minimum standards-breastfeeding areas and feeding breaks, child care accessibility, leave for expectant parents, financial and medical benefits, and employment protection-UNICEF encourages factories to have family-friendly policies for their employees as part of the Mothers Work initiative. In Bangladesh, breastfeeding is highly regarded. Nearly all (98%) infants who are still nursing at 20-23 months of age were breastfed at some time throughout their development. But there are many of places where feeding babies and young kids might be done far better. A typical delay in the start of breastfeeding is one hour after birth, when only 43% of neonates are nursed (BDHS, 2007). About 64% of infants less than six months breastfeed exclusively due to the early introduction of supplemental meals and other liquids (BDHS, 2011). Additionally, supplementary feeding can begin too late because only around 21% of neonates received it, as recommended. A project of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, the National Nutrition Services (NNS) of the Health, Population, Nutrition Sector Program (HPNSP) sought to train field-level staff in the health and family planning sectors to improve IYCF practices. There is now a three-day training program available.

Guideline for Complementary Food Practices

In order to adequately fulfill a child's nutritional needs, a variety of meals must be offered. This is referred to as dietary diversity. To meet daily nutrient and energy requirements, a minimum dietary diversity (MDD) of four or more of the seven food groups is required. This guarantees that the child will likely have at least one food from an animal source and one fruit or vegetable that day in addition to a basic meal (grain, root, or tuber).

|

Grains, roots, and tubers |

Rice, wheat, maize, jowar, ragi, potato, sweet-potato |

|

Legumes and nuts |

Pulses, nuts, oil-seeds, dry fruits |

|

Vitamin-A rich fruits and vegetables |

Orange/yellow/green vegetables or fruits such as mango, carrot, papaya, and tomato |

|

Other fruits and vegetables |

Locally available, fresh fruits and vegetables, preferably seasonal and inexpensive |

|

Dairy products |

Milk, curd, yogurt, butter, and paneer |

|

Eggs |

Eggs |

|

Flesh Foods |

Meat, fish, poultry, and organ meats |

Table 2: The various food groups for complementary food practices.

There are many different commercial meals available on the market for feeding neonates. They are expensive and frequently offer exaggerated health claims. Even if they are convenient, ready-to-eat food, fake food, and packaged food are frequently not the healthiest or best choices for feeding kids. Children's meals should be prepared as much as possible at home with readily available ingredients. Children's health organizations advise against marketing commercial meals for feeding infants and young children (under 2 years old).

Quality, Frequency and Amount of Complementary Food Practicing

Nutrition is important, especially during the first 1,000 crucial days, for a child to have optimal growth and development. Feeding practices that are satisfying and pleasant for both mother and infant are essential for the child's emotional development. The mother and family need to be motivated, encouraged, educated, and supported in regards to proper feeding practices. You may ensure that your child enjoys the experience by feeding them delicately. Every community has a staple food, such as wheat or rice, that is consumed on a daily basis in large quantities. The typical handmade meal must be mentioned by the parents. Families in rural locations could advocate producing food in a kitchen garden, gathering it, cooking it, and storing it whichever suits them. Urban inhabitants may be able to purchase the essential meals depending on their tastes and financial situation. Staple meals are easily cooked and are a great source of calories and protein. Through the following measures, the foods should be secure and hygienic:

- Keep things tidy to safeguard food.

- It is necessary to offer food that seems to be fresh and smells delicious.

- Perishable foods, such as meat, milk, and eggs, as well as cooked meals must be kept in a refrigerator.

- If there is no refrigerator available, properly cover the dish and serve it to the child within two hours.

If the food has been sitting out for a while, reheat it before eating to get rid of any hazardous bacteria. During the meal's preparation, rats, mice, cockroaches, flies, and dust should be avoided.

|

6-8 months |

Begin with mashed foods or thick porridges |

Daily 2–3 meals along with frequent breastfeeding |

In the beginning, 2–3 tablespoon-full |

|

9-11 months |

Mashed foods, finely chopped, and foods that can be picked up by baby |

Daily 3 meals with continued breastfeeding plus offer 1–2 additional snacks |

1/2 cup/bowl (125 mL) |

|

1-2 years |

Staple family foods, mashed or chopped (if required |

Daily 3–4 meals with |

3/4 to one cup/bowl (250 mL) |

Table 3: The following complementary food schedule can be followed

Discussion

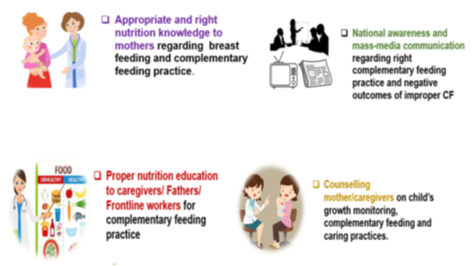

Thanks to the nutrition guidance of health experts, children between the ages of six months and two years benefit from higher calorie intake, more frequent feedings, and a wider variety of food. The following approach can be used to envision such a significant outcome: Health workers' knowledge of nutrition and food science may be updated or expanded via nutrition education. Indeed, two RCTs conducted in Brazil [16] and India [22] found that health workers with nutrition training had better nutritional knowledge. The knowledge of nutrition that health professionals possess may be updated through nutrition training, which may also educate them of new information that is pertinent to their working environment [20,24,25,28]. Addressing the causes of undernutrition in their local communities would enable them to communicate more effectively, offer counseling, and treat the condition [12,16,24,25]. When giving caretakers guidance when they visit medical facilities, knowledgeable health professionals may share nutritional information [17]. Similar to this, trained health professionals may get in touch with caregivers via outreach and home visits even in far-off places, and they might do this this manner [14,21]. The caregivers who sought guidance from medical experts who had received nutrition training showed improved nutrition knowledge and memory [25,28]. Change-makers might include the caregivers who got therapy. Parents who receive frequent counseling and have access to the latest nutrition knowledge can better feed their children [17,28]. Examples of such behaviors include eating frequently, properly mixing high-quality meals, consuming more energy, and altering one's diet. Children's growth might be improved by lowering their risk of undernutrition [21]. Furthermore, foodborne infections may be reduced, and food preparation hygiene might be increased [19]. These are other elements that have a role in undernutrition. It has been demonstrated that knowledgeable health professionals' guidance on nutrition is helpful even in areas with a shortage of food [18,21]. For instance, about a third of the households in the Bangladeshi RCT experienced food insecurity and poverty. Despite these obstacles, they were motivated by and changed their eating habits by the dietary advice given by knowledgeable health specialists. They could then serve their children meals that are properly balanced [31]. Parents who intend to undertake breastfeeding supplementary feeding should be aware of the following guidelines:

- After the 180-day mark has passed, begin supplementary feedings.

- Maintain breastfeeding for two more years while giving the appropriate supplementary nutrients.

- Prefer making your own meals;

- Dispense semisolid food (Avoid watery food such as soups, fruit juices, and animal milk); (clean, fresh, cheap, and easily available)

- Prefer balanced meals made with ingredients that are readily available locally (cereal, legumes, and veggies).

- Introduce one meal at a time; as soon as the child starts to accept it, go on to a next recipe.

In general, adding ghee, oil, oil-seed powder, and fats to food enhances its caloric content and flavor, with the exception of children who are overweight or obese. Never force a feeding. Give the child as much as they consume. Take note of the child's weight.

Figure 1: Right Measures to be taken for implementing the right complementary feeding practice in Bangladesh

Conclusion

A health practitioner who has taken nutrition training may alter the way that young newborns are fed. These habits include things like feeding frequency, caloric consumption, and dietary diversity. It is essential in locations where food supply is short to produce training materials based on the local context and to provide guidance on how to identify meals that are easily available, affordably priced, and deserving. A local community information source that is readily available and reliable may also be offered by trained health professionals. In this regard, a long-term strategy to improve the nutritional condition of young children may be greatly aided by training health professionals about nutrition. MNP delivery through standard health services, neighborhood outreach, market-based models, and other channels has the ability to raise knowledge of critical IYCF practices broadly speaking and enhance contact between carers and providers of IYCF counselling and support. This is so that it may capitalize on a policy climate that is hospitable and be supplemented by strategic, comprehensive BCC activities. With regular follow-up at the home level, the use of hands-on methods for educating caregivers on how to prepare meals and serve them to their young children, and the use of new resources, MNP treatments have the potential to give present IYCF programs a new focus and focus. This may be achieved, however, only if MNP intervention design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation activities are fully integrated into IYCF programming. Sustainable development initiatives that are centered on food have had a hard time getting off the ground. Organizations with a focus on the community and public health have shunned these tactics in favor of initiatives that have produced tangible outcomes quickly. It has been demonstrated by several developing nations, international agencies, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that food-based strategies offer a workable, inexpensive, and locally durable solution to micronutrient shortages.

References

- Oldewage-Theron WH, Dicks EG, Napier CE. Poverty, household food insecurity and nutrition: coping strategies in an informal settlement in the Vaal Triangle, South Africa. Public Health 120 (2006): 795-804

- Zezza A, Tasciotti L. Urban agriculture, poverty, and food security: empirical evidence from sample of developing countries. 2010, Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization

- Lo YT, Chang YH, Lee MS, et al. Dietary diversity and food expenditure as indicators of food security in older Taiwanese. Appetite 58 (2012): 180-187.

- Blumberg S, Bialostosky K, Hamilton W, et al. The effectiveness of a short form of the household food security scale. Am J Public Health 89 (1999): 1231-1234.

- Bhandari N, Mazumder S, Bahl R, et al. Use of multiple opportunities for improving feeding practices in under-twos within child health programs. Health Policy Plan 20 (2005): 328-336.

- Stang J, Rehorst J, Golicic M. Parental feeding practices and risk of childhood overweight in girls: implications for dietetics practice. J Am Diet Assoc 104 (2004): 1076-1079.

- Dussault G, Franceschini MC. Not enough there, too many here: understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce. Hum Resour Health 4 (2006): 12-19.

- Meijers JM, Halfens RJ, Dassen T, et al. Malnutrition in Dutch health care: prevalence, prevention, treatment, and quality indicators. Nutrition 25 (2009): 512-519

- Valle NJ, Santos I, Gigante DP, et al. Household trials with very small samples predict responses to nutrition counseling intervention. Food Nutr Bull 24 (2003): 343-349.

- Aboud FE, Moore AC, Akhter S. Effectiveness of a community-based responsive feeding programme in rural Bangladesh: a cluster randomized field trial. Matern Child Nutr 4 (2008): 275-286

- Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 371 (2008): 243-260

- State of the World's children 2008. 2007, New York, USA: United Nations Children's Fund.

- Palwala M, Sharma S, Udipi SA, et al. Nutritional quality of diets fed to young children in urban slums can be improved by intensive nutrition education. Food Nutr Bull 30 (2009): 317-326.

- Building a future for women and children. The 2012 report. 2012, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2012).

- Ahmed F. Micronutrient deficiencies among children and women in Bangladesh: progress and challenges. Journal of Nutritional Science 5 (2016): 1-12.

- Eneroth H. Maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation has limited impact on micronutrient status of Bangladeshi infants compared with standard iron folic acid supplementation. Journal of Nutrition 140 (2010): 618.

- Dewey KG, Adu-Afarwuah S. Systematic review of the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. Matern Child Nutr 4 (2008): 24-85.

- Merrill RD. High prevalence of anemia with lack of iron deficiency among women in rural Bangladesh: a role for thalassemia and iron in groundwater. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 21 (2012): 416-422.

- Penland JG, Sandstead HH, Alcock NW et al. A preliminary report: effects of zinc and micronutrient repletion on growth and neuropsychological function of urban Chinese children (2011).

- Bangladesh National Nutrition Survey 1995-96. Institute of Nutrition and Food Science, University of Dhaka (1998).

- Bhutta ZA. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost. Lancet 382 (2013): 452-477.

- Assessment of study quality. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 426. Edited by: Higgins J, Green S, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons LTD (2009): 79-87.

- Santos I, Victora CG, Martines J, et al. Nutrition counseling increases weight gain among Brazilian children. J Nutr 131 (2011): 2866-2873.

- Guldan GS, Fan HC, Ma X, et al. Culturally appropriate nutrition education improves infant feeding and growth in rural Sichuan, China. J Nutr 130 (2000): 1204-1211.

- Saloojee H, De Maayer T, Garenne M, et al. What's new? Investigating risk factors for severe childhood malnutrition in a high HIV prevalence South African setting. Scand J Public Health Suppl 69 (2007): 96-106.

- Xiao QG, Xi W, Xin YW, et al. Effects of different feeding frequencies on the growth, plasma biochemical parameters, stress status, and gastric evacuation of juvenile tiger puffer fish (Takifugu rubripes), Aquaculture (2022).

- Vitolo MR, Rauber F, Campagnolo PD, et al. Maternal dietary counseling in the first year of life is associated with a higher healthy eating index in childhood. J Nutr 140 (2010): 2002-2007

- Sunguya B, Koola J, Atkinson S. Infections associated with severe malnutrition among hospitalized children in East Africa. Tanzan Health Res Bull 8 (2006): 189-192.

- Roy SK, Fuchs GJ, Mahmud Z, et al. Intensive nutrition education with or without supplementary feeding improves the nutritional status of moderately-malnourished children in Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr 23 (2005): 320-330.

- Akl EA, Kennedy C, Konda K, et al. Using GRADE methodology for the development of public health guidelines for the prevention and treatment of HIV and other STIs among men who have sex with men and transgender people. BMC Publ Health 12 (2012): 386

- Shi L, Zhang J. Recent evidence of the effectiveness of educational interventions for improving complementary feeding practices in developing countries. J Trop Pediatr 57 (2011): 91-98