Patient and Caregiver Perspectives on the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale and the Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics-Short Form

Article Information

Maud Beillat1, T. Michelle Brown2*, Dana B. DiBenedetti2, Dieter Naber3

1HE and HTA Management Department, Lundbeck SAS, Quai du President Roosevelt 37-45, Issy-les-Moulineaux 92445, France

2Patient-Centered Outcomes Assessment, RTI Health Solutions, 200 Park Offices Drive, Research Triangle Park, NC, 27709, United States

3Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Medical Center, Hamburg Eppendorf, Martinistreet 52, Building 37, Hamburg 20246, Germany

*Corresponding Author: Michelle Brown T, RTI Health Solutions, 3040 Cornwallis Road, Post Office Box 12194, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709, North Carolina, United States

Received: 25 April 2017; Accepted: 03 May 2017; Published: 08 May 2017

Share at FacebookAbstract

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and functioning are associated with outcomes in schizophrenia; however, there is heterogeneity in measured HRQOL and functioning concepts and incongruence among raters (patients, caregivers, and physicians). This study aimed to explore the meaning and relevance to patients and caregivers of the concepts measured in two commonly used measures of HRQOL and functioning in schizophrenia: the clinician-administered Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (QLS) and the patient-rated Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form (SWN-S). Interviews with adults with schizophrenia (n=12) and focus groups with caregivers (n=17) were conducted to assess the meaning and importance of concepts from these measures. For both patients and caregivers, the Intrapsychic Foundations domain of the QLS and the Mental Functioning domain of the SWN-S were identified as the most important contributors to patient HRQOL and functioning. General congruence was observed in patients’ and caregivers’ interpretations of the concepts on both measures.

Keywords

Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale; Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form; Schizophrenia; Patient-reported outcome

Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale articles Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale Research articles Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale review articles Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale PubMed articles Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale PubMed Central articles Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale 2023 articles Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale 2024 articles Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale Scopus articles Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale impact factor journals Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale Scopus journals Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale PubMed journals Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale medical journals Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale free journals Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale best journals Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale top journals Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale free medical journals Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale famous journals Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale Google Scholar indexed journals Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form articles Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form Research articles Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form review articles Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form PubMed articles Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form PubMed Central articles Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form 2023 articles Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form 2024 articles Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form Scopus articles Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form impact factor journals Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form Scopus journals Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form PubMed journals Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form medical journals Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form free journals Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form best journals Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form top journals Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form free medical journals Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form famous journals Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics–Short Form Google Scholar indexed journals Schizophrenia articles Schizophrenia Research articles Schizophrenia review articles Schizophrenia PubMed articles Schizophrenia PubMed Central articles Schizophrenia 2023 articles Schizophrenia 2024 articles Schizophrenia Scopus articles Schizophrenia impact factor journals Schizophrenia Scopus journals Schizophrenia PubMed journals Schizophrenia medical journals Schizophrenia free journals Schizophrenia best journals Schizophrenia top journals Schizophrenia free medical journals Schizophrenia famous journals Schizophrenia Google Scholar indexed journals Patient-reported outcome articles Patient-reported outcome Research articles Patient-reported outcome review articles Patient-reported outcome PubMed articles Patient-reported outcome PubMed Central articles Patient-reported outcome 2023 articles Patient-reported outcome 2024 articles Patient-reported outcome Scopus articles Patient-reported outcome impact factor journals Patient-reported outcome Scopus journals Patient-reported outcome PubMed journals Patient-reported outcome medical journals Patient-reported outcome free journals Patient-reported outcome best journals Patient-reported outcome top journals Patient-reported outcome free medical journals Patient-reported outcome famous journals Patient-reported outcome Google Scholar indexed journals delusions articles delusions Research articles delusions review articles delusions PubMed articles delusions PubMed Central articles delusions 2023 articles delusions 2024 articles delusions Scopus articles delusions impact factor journals delusions Scopus journals delusions PubMed journals delusions medical journals delusions free journals delusions best journals delusions top journals delusions free medical journals delusions famous journals delusions Google Scholar indexed journals hallucinations articles hallucinations Research articles hallucinations review articles hallucinations PubMed articles hallucinations PubMed Central articles hallucinations 2023 articles hallucinations 2024 articles hallucinations Scopus articles hallucinations impact factor journals hallucinations Scopus journals hallucinations PubMed journals hallucinations medical journals hallucinations free journals hallucinations best journals hallucinations top journals hallucinations free medical journals hallucinations famous journals hallucinations Google Scholar indexed journals heterogeneity articles heterogeneity Research articles heterogeneity review articles heterogeneity PubMed articles heterogeneity PubMed Central articles heterogeneity 2023 articles heterogeneity 2024 articles heterogeneity Scopus articles heterogeneity impact factor journals heterogeneity Scopus journals heterogeneity PubMed journals heterogeneity medical journals heterogeneity free journals heterogeneity best journals heterogeneity top journals heterogeneity free medical journals heterogeneity famous journals heterogeneity Google Scholar indexed journals physicians articles physicians Research articles physicians review articles physicians PubMed articles physicians PubMed Central articles physicians 2023 articles physicians 2024 articles physicians Scopus articles physicians impact factor journals physicians Scopus journals physicians PubMed journals physicians medical journals physicians free journals physicians best journals physicians top journals physicians free medical journals physicians famous journals physicians Google Scholar indexed journals Intrapsychic Foundations articles Intrapsychic Foundations Research articles Intrapsychic Foundations review articles Intrapsychic Foundations PubMed articles Intrapsychic Foundations PubMed Central articles Intrapsychic Foundations 2023 articles Intrapsychic Foundations 2024 articles Intrapsychic Foundations Scopus articles Intrapsychic Foundations impact factor journals Intrapsychic Foundations Scopus journals Intrapsychic Foundations PubMed journals Intrapsychic Foundations medical journals Intrapsychic Foundations free journals Intrapsychic Foundations best journals Intrapsychic Foundations top journals Intrapsychic Foundations free medical journals Intrapsychic Foundations famous journals Intrapsychic Foundations Google Scholar indexed journals psychosurgery articles psychosurgery Research articles psychosurgery review articles psychosurgery PubMed articles psychosurgery PubMed Central articles psychosurgery 2023 articles psychosurgery 2024 articles psychosurgery Scopus articles psychosurgery impact factor journals psychosurgery Scopus journals psychosurgery PubMed journals psychosurgery medical journals psychosurgery free journals psychosurgery best journals psychosurgery top journals psychosurgery free medical journals psychosurgery famous journals psychosurgery Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

1. Introduction

Symptoms of schizophrenia include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech and behavior, and negative symptoms (e.g., diminished emotional expression, apathy) [1]. Patients with schizophrenia may have deficits in social and occupational functioning, self-care abilities, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [1-3]. Patients with higher levels of HRQOL and functioning are less likely to relapse and are more likely to be adherent with treatment, and early HRQOL improvements with treatment are associated with symptomatic remission and better long-term outcomes [2, 4]. As such, better understanding of the importance and role of HRQOL and functioning in patients with schizophrenia is critical to successful long-term treatment.

Despite studies demonstrating that treatment is associated with better outcomes relating to higher levels of HRQOL and functioning in patients with schizophrenia, there remains considerable heterogeneity in these concepts as they relate to schizophrenia [5]. A recent review, which found that 35 different generic or disease-specific HRQOL measures had been used in studies in schizophrenia, noted a lack of consensus on the underlying concept of HRQOL in schizophrenia [2]. Moreover, incongruence has been observed in HRQOL and functioning ratings provided by patients, clinicians, and caregivers. For example, differences in HRQOL scores and functioning outcomes have been reported depending on whether patients or clinicians complete the measures, with clinicians generally providing lower ratings than patients [6-8]. In addition, although caregivers are increasingly involved in decisions relating to patient care and treatment, congruence between HRQOL ratings provided by caregivers and patients [9], as well as those between caregivers and clinicians [10], has been inconsistent. In general, HRQOL and functioning ratings provided by proxies are often lower than ratings provided by patients with schizophrenia.

The objective of this study was to further explore patients′ and caregivers′ perceptions of the meaning and relevance of concepts measured in two commonly used measures in schizophrenia, the clinician-administered Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (QLS) and the patient-rated Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics?Short Form (SWN-S). Specifically, we aimed to gain a better understanding of which concepts relating to patient HRQOL and daily functioning were most important to patients and caregivers. Additionally, we wanted to better understand the congruence between patients and caregivers on the meaning and importance of concepts associated with HRQOL and functioning.

2. Material and Methods

Individual interviews with patients with schizophrenia and focus groups with caregivers of patients with schizophrenia were conducted in the United States (US). Medical recruiters from two US-based qualitative research facilities (in Fort Lee, NJ, and Dallas, TX) recruited and screened individuals from their database of potential participants. Patients meeting the inclusion criteria (aged 18 years or older; community dwelling; clinician-administered diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; current use of one or more atypical antipsychotic medications) per self-report were eligible to participate in the individual interviews. Caregivers meeting the inclusion criteria (aged 18 years or older; informal caregiver [e.g., family, friend] of a patient with a clinician-administered diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; provided 5 hours or more per week of direct contact to a patient with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder) per self-report were eligible to participate in the focus groups. The study was reviewed and approved by an institutional review board before any recruitment activities began. Both patients and caregivers provided written, informed consent before participating in the interviews or focus groups, respectively. To ensure that patients fully understood the nature and content of the interview procedure, prior to written consent, patients were asked to verbalize their understanding of the interview purpose and process in their own words. The two PhD level psychologists conducting the interviews gauged each patient′s level of understanding and functioning and determined their appropriateness to continue study participation.

The interviews and focus groups assessed concepts (domains and items) from the QLS and SWN-S. The QLS, a clinician-administered semi-structured interview, assesses the intrapsychic, social, and negative symptoms of schizophrenia and their potential consequences on patient functioning [11]. It includes 21 concepts (including two that are based solely on clinician observation and were not included in this study: "functioning at full potential" and the "ability to engage and communicate with another person") across four domains (Interpersonal Relations, Instrumental Role, Intrapsychic Foundations, and Common Objects and Activities). Each QLS concept is scored from 0 (severe impairment) to 6 (normal or unimpaired functioning). Mean scores are calculated for each domain, and the total score for all concepts ranges from 0 to 126; higher scores indicate normal or unimpaired functioning. For the purposes of the patient interviews and caregiver focus groups, the domain names and example questions (provided to the clinician administering the interview) were modified from their original form and summarized to foster participant understanding and feedback (see Table 1). Table 1: QLS Domain and Concept Summary.

Domain and Conceptsa |

Patients (n = 12) |

Caregivers (n = 17) |

||||

|

|

Clearb |

More/Less Importantc |

More/Less Likely to Changed |

Clearb |

More/Less Importantc |

More/Less Likely to Changed |

|

Interpersonal Relations |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

(Relationships and Social Activities) |

||||||

|

Relationships with family and friends |

? |

? |

|

? |

? |

|

|

Acquaintances/?people you know, not close with |

? |

? |

|

? |

? |

|

|

Involvement in social activity with other people |

? |

|

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

Concern/?interest from other people in well-being |

? |

|

|

? |

|

|

|

Planning a social activity with someone |

? |

? |

|

? |

|

|

|

Avoiding other people, being withdrawn |

? |

|

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

Romantic relationships |

? |

? |

|

? |

? |

|

|

Instrumental Role |

? |

|

? |

? |

|

? |

|

(Daily Responsibilities) |

||||||

|

Work/school; take care of home/family |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

Being successful with work/school, etc. |

? |

? |

|

? |

? |

|

|

Feeling satisfied with work, job, school, etc. |

? |

? |

|

? |

? |

|

|

Intrapsychic Foundations |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

(Feelings and Life Satisfaction) |

||||||

|

Life goals |

? |

? |

|

? |

|

|

|

Motivation |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

Interest in your surroundings |

? |

|

|

? |

|

|

|

Feeling happy or being able to enjoy things |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

Time spent doing nothing |

? |

|

|

? |

? |

|

|

Appreciation/?interest in others′ beliefs/?opinions |

|

? |

|

|

? |

|

|

Common Objects and Activities |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

? |

|

(Important Things You Have and Do) |

||||||

|

Things to have |

|

|

? |

|

? |

? |

|

Things to do |

|

|

? |

|

? |

? |

QLS = Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale.

aThe domain and concept (i.e., example questions) were modified from their original form (shown in italics) and summarized to facilitate participant understanding and feedback; bThe domain or concept was generally clear (?) or not clear (?) to patients or caregivers. The absence of a symbol indicates that patients and caregivers did not identify the domain or concept as being especially clear or unclear; cThe domain or concept was especially important (?) or not important or relevant (?) to patients or caregivers. The absence of a symbol indicates that patients and caregivers did not identify the domain or concept as being especially important or unimportant; dPatients or caregivers found the domain or concept especially likely or prone to change (?) or not likely or prone to change (?) based on fluctuations in patients′ level of functioning or symptoms. The absence of a symbol indicates that patients and caregivers did not identify the domain or concept as being especially likely or unlikely to change.

Note: Underlined symbols (?, ?) denote a discrepancy in feedback between the patients and caregivers.

The 20-item SWN-S is a patient-rated scale designed to investigate the subjective effects of antipsychotics on psychopathology, well-being, and adherence [12]. It includes five domains (Mental Functioning, Self-control, Emotional Regulation, Physical Functioning, and Social Integration), each including four items with two negative and two positive statements. Each item is scored from 1 (not at all) to 6 (very much). Scores are calculated for each domain, with total scores ranging from 20 to 120 points; higher scores indicate better well-being.

The interviews and focus groups were conducted according to a semi-structured interview guide. Adjusted for each participant′s level of functioning, questions were asked about the meaning and clarity of the QLS and SWN-S domains, concepts, and/or items (e.g., What does the domain/concept/item mean to you?). Participants were also asked about the likelihood or tendency of each domain and concept to change based on fluctuations in the patients′ level of functioning and/or degree of symptoms (e.g., Can this domain/concept improve? Does it change from day to day, and how so?). In addition, participants were asked to identify the concepts within each QLS domain that were most important to the overall domain, as well as any that were least important or not relevant to them (e.g., Is this an important concept, and how so?). Due to the nature of the items in each SWN-S domain (i.e., containing both positively and negatively worded items assessing a similar concept), participants were not asked to provide feedback on the importance and change for each individual item; instead, they were asked more generally about the item concepts within each domain.

Participants were then asked to rank-order the four (QLS) or five (SWN-S) domains of each measure according to their perceptions of importance to them (or to the patients with schizophrenia for whom they provide care) and contribution to HRQOL and functioning (e.g., 1 = most important, 2 = next most important). Handouts including the instrument domain names and concepts or items were provided to each patient and caregiver to ease discussion, feedback, and the ranking exercise related to each scale. (Measure domains and concepts/items are shown in Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2: SWN-S Domain and Item/Concept Summary.

Domains and Items |

Patients (n = 12) |

Caregivers (n = 17) |

||||

|

Cleara |

More/Less Importantb |

More/Less Likely to Changec |

Cleara |

More/Less Importantb |

More/Less Likely to Changec |

|

|

Mental Functioning |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

• I find it easy to think. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• I am imaginative and full of ideas. |

||||||

|

• My thinking is difficult and slow. |

||||||

|

• My thoughts are flighty and undirected. I find it difficult to think clearly. |

||||||

|

Self-control |

? |

|

? |

? |

|

? |

|

• I feel powerless and not in control of myself. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• My feelings and behavior are inappropriate to situations. I get upset about small things. Important things hardly affect me at all. |

||||||

|

• I find it easy to draw a line between myself and others.d |

||||||

|

• My feelings and behavior are appropriate to situations. |

||||||

|

Emotional Regulation |

? |

|

? |

? |

|

|

|

• I have no hope for the future. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• My thoughts and emotions are numb. Nothing matters to me. |

||||||

|

• I take interest in what is happening around me, and it is important to me. |

||||||

|

• I am full of confidence. Everything will be alright.d |

||||||

|

Physical Functioning |

? |

|

? |

? |

|

? |

|

• I feel very comfortable with my body. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• My body feels familiar, like it belongs to me.d |

||||||

|

• I feel drained and exhausted. |

||||||

|

• My body is a burden to me.d |

||||||

|

Social Integration |

? |

|

? |

? |

|

? |

|

• I am very shy about approaching people and making social contact. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• My environment seems friendly and familiar to me. |

||||||

|

• I find it easy to interact with people around me. |

||||||

|

• I perceive my environment as being changed, strange, and threatening.d |

||||||

SWN-S = Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics-Short Version.

aThe overall domain was generally clear (?) or not clear (?) to patients or caregivers. The absence of a symbol indicates that patients and caregivers did not identify the domain as being especially clear or unclear; bThe domain or concept was especially important (?) or not important or relevant (?) to patients or caregivers. The absence of a symbol indicates that patients and caregivers did not identify the domain as being especially important or unimportant; cPatients or caregivers found the domain especially likely or prone to change (?) or not likely or prone to change (?) based on fluctuations in patients′ level of functioning or symptoms. The absence of a symbol indicates that patients and caregivers did not identify the domain or concept as being especially likely or unlikely to change; dThis individual concept within the domain was not clear to patients or caregivers.

Note: Underlined symbols (?, ?) denote a discrepancy in feedback between the patients and caregivers.

3. Results

3.1 Participants

A total of 12 interviews with patients and four focus groups with caregivers (n = 17) were conducted. Among the 12 patients, the mean time since diagnosis of schizophrenia was 16.3 years (range, 2-47 years). Patients′ living situation varied: 41.7% were living alone, 25.0% were living with spouse or a partner, and 33.3% were living with other family members. Most caregivers (12 of 17, or 70.6%) were female, and the mean age of caregivers (46.3 years) was slightly older than that of patients (42.3 years). Table 3 presents the patient and caregiver characteristics.

Table 3: Patient and Caregiver Characteristics.

|

Characteristic |

Patients |

Caregivers |

|

Sex, n (%) |

||

|

Male |

7 (58.3) |

5 (29.4) |

|

Female |

5 (41.7) |

12 (70.6) |

|

Age, years |

||

|

Mean (range) |

42.3 (25-62) |

46.3 (24-70) |

|

Race/ethnicity, n (%) |

||

|

White |

5 (41.7) |

8 (47.1) |

|

African American |

4 (33.3) |

5 (29.4) |

|

Asian |

1 (8.3) |

1 (5.9) |

|

Hispanic/Latino |

1 (8.3) |

2 (11.8) |

|

Other |

1 (8.3) |

1 (5.9) |

|

Patients′ current atypical antipsychotic medication,a n (%) |

||

|

Aripiprazole |

4 (33.3) |

- |

|

Risperidone |

4 (33.3) |

- |

|

Paliperidone |

3 (25.0) |

- |

|

Ziprasidone |

1 (8.3) |

- |

|

Clozapine |

2 (16.7) |

- |

|

Quetiapine |

2 (16.7) |

- |

aTotal percentage may exceed 100%, as participants could report more than one atypical antipsychotic medication.

3.1 Domains and concepts3.2.1 Heinrichs-Carpenter quality of life scale (QLS): ?Table 3 summarizes patient and caregiver feedback related to the QLS domains and concepts, specifically participants′ interpretation of the QLS domains and concepts, the domains and concepts that were especially important or relevant (as well as those that were not relevant), and the domains and concepts that were most or least likely to change with variations in patients′ day-to-day functioning or symptomatology. Overall, both patients and caregivers found most of the QLS domains and concepts to be clear and understandable. However, patients′ and caregivers′ impressions regarding the importance of some domains and concepts varied. For example, caregivers considered the Common Objects and Activities domain to be more important than patients did; in addition, caregivers found concepts surrounding patients′ social activities and interactions more important than patients did. Overall, both patients and caregivers found most concepts in this domain to be prone to change with day-to-day variations in functioning. The following sections provide details regarding patients′ and caregivers′ feedback on each QLS domain and the concepts within each.

3.2.1.1 Interpersonal Relations: Patients and caregivers understood the Interpersonal Relations (referred to as "Relationships and Social Activities" for clarity) domain of the QLS to include relationships with family and friends and activities with these individuals. The concepts in this domain that were most important to patients and caregivers related to family and household relationships, followed by relationships with friends. However, compared with patients, caregivers placed additional emphasis on the patients′ social interactions and activities?perceiving social interactions and the interaction with others (i.e., not being withdrawn) as not only highly likely to change but two of the most important concepts within this domain. Many caregivers believed that patients who engage in and maintain close relationships with others and interact socially may be less impaired or affected by their disease, and some caregivers expressed the belief that relationships and social interaction could minimize the symptoms of schizophrenia. Most patients considered the concepts relating to romantic relationships and planning social activities to be irrelevant to them or their functioning. When asked about which concepts tended to change or vary the most based on their day-to-day functioning, many patients commented on being less social and avoiding others, both within and outside the home, when they were not functioning as well. A concept in this domain that was less clear to patients related to more distant relationships (i.e., acquaintances)-patients were unsure how to define their relationships with individuals who were neither friends nor family.

3.2.1.2 Instrumental Role: Patients and caregivers understood the Instrumental Role (referred to as "Daily Responsibilities" for clarity) domain of the QLS to relate to daily activities such as household chores, caring for family members, working, aspects of self-care, volunteer work, or activities at treatment centers. Caregivers believed that the Instrumental Role domain was generally important to patients′ functioning. The concepts in this domain that patients considered most important related to being able to work (regardless of whether they actually did work) and taking care of one′s family and home. Both patients and caregivers placed less importance on success or satisfaction with work and more importance on patients′ ability to work, feel productive and purposeful, and fulfill daily responsibilities. In fact, caregivers considered patients′ ability to work and maintain other responsibilities to be central to patients′ well-being and happiness. When asked about which concepts tended to change or vary the most based on their day-to-day functioning, many patients referenced their activities and chores at home and how they may vary based on their level of motivation to get things done.

3.2.1.3 Intrapsychic Foundations: Patients and caregivers generally understood the Intrapsychic Foundations (referred to as "Feelings and Life Satisfaction" for clarity) domain of the QLS to relate to their feelings about their life and future aspirations. This domain resonated strongly with both patients and caregivers, especially patients′ mood and motivation from day to day, the concepts participants considered most important in this domain. Patients, more than caregivers, also considered life goals to be important, as most patients expressed their aspirations and goals for the future (e.g., to live independently or get a job). Patients generally interpreted the concept about time spent doing nothing as positive, relating to time spent relaxing or not doing anything in particular (e.g., "down time"), whereas many caregivers interpreted time spent doing nothing as time being wasted. A less important concept to both patients and caregivers was appreciation or interest in other people′s beliefs or opinions. Many patients, especially those struggling with paranoia or depressed mood, believed that they needed to focus instead on themselves rather than what others thought about them. Patients and caregivers also noted that this domain as a whole and most of the concepts within it?especially mood and motivation?were prone to change with variations in functioning, and many caregivers had observed broad variability in patients′ motivation and mood. Most patients also expressed the need for improvement in this domain.

3.2.1.4 Common Objects and Activities: Patients and caregivers interpreted the Common Objects and Activities (referred to as "Important Things to Have and Do" for clarity) domain of the QLS as having important possessions and responsibilities. Many patients did not transfer this understanding to being a functional member in society, but they liked owning selected items and having responsibilities that did not cause undue stress. Although patients did not find either concept in this domain especially important, caregivers acknowledged the relevance of both concepts in this domain. Neither patients nor caregivers felt that this domain would change from day to day based on patients′ level of functioning.

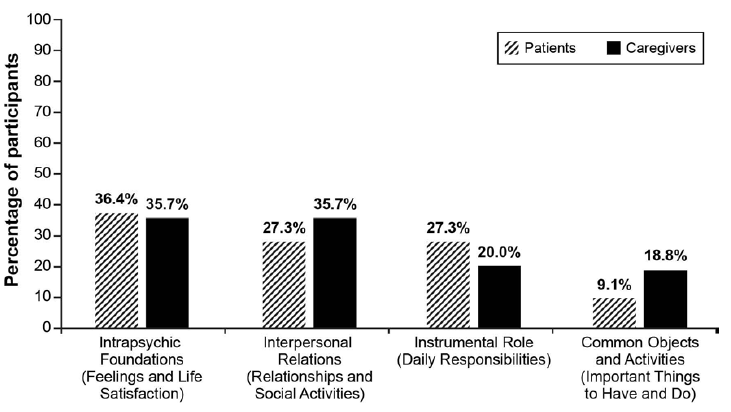

3.2.1.5 Relative Domain Importance: Figure 1 presents the proportion of patients and caregivers identifying each of the QLS domains as most important. The Intrapsychic Foundations domain was one of the most important domains to both patients and caregivers in defining and contributing to patient HRQOL and functioning. For patients, this domain was more important than any of the other QLS domains, whereas caregivers placed equal importance on the Intrapsychic Foundations and Interpersonal Relations domains. For patients, the Common Objects and Activities domain was found to be less important than any of the other three domains.

Figure 1: Proportion of patients and caregivers ranking each QLS domain as most important.

Note: One patient was not asked to provide importance rankings across the four QLS domains due to limited cognitive functioning. Thus, the patient sample size was 11, rather than 12, for this ranking task. In addition, 1 to 3 caregivers did not provide importance rankings for some of the four QLS domains; thus, the caregiver sample size varied across the domains from 14 to 16.

3.2.2 Subjective Well-being Under Neuroleptics?Short Form (SWN-S): ?Table 1 summarizes patient and caregiver feedback related to the SWN-S domains and concepts, specifically participants′ impressions of the clarity of the SWN-S domains and concepts, the domains and concepts that were especially important or relevant (as well as those that were not relevant), and the domains and concepts that were most or least likely to change with variations in patients′ day-to-day functioning or symptomatology. Patients and caregivers generally found most of the SWN-S domains and concepts to be clear, although several items were unclear or confusing to both patients and caregivers. For both patients and caregivers, the domains of Mental Functioning, Emotional Regulation, and Social Integration were thought to be highly likely to change and Physical Functioning less likely to change. Unlike caregivers, patients believed that concepts within the Self-control domain were less likely to change. The following sections provide details regarding patients′ and caregivers′ feedback on the SWN-S domains and the concepts within each.

3.2.2.1 Mental Functioning: Patients and caregivers found this domain and all concepts in it to be clear, and both patients and caregivers noted the importance of this domain. Patients could relate, based on their current or past functioning, to difficulties with cognitive processes (and how they think). In interpreting these items, caregivers referred to patients′ behavior ranging from blank stares to the ability to engage and converse in a meaningful manner. Both patients and caregivers noted the potential for variability in this domain based on level of functioning; most caregivers indicated that they generally were able to communicate effectively with their loved ones on most days, and that only on "bad" days was the individual′s thinking too clouded to converse clearly.

3.2.2.2 Self-control: Patients and caregivers generally understood this domain and most concepts within it. When discussing this domain, patients often referred to their ability (or lack thereof) to control their feelings and behaviors as well as the appropriateness of them. Whereas some patients understood the item referring to "drawing a line between myself and others" and interpreted this item to pertain to what they considered to be appropriate boundaries, many patients, as well as several caregivers, found this item confusing. For example, one patient described this item as how she tended to separate herself from others with an unhealthy level of emotional and physical isolation; another patient was unsure of its meaning and attempted to reference an actual line between himself and others. With regard to the item about feeling "powerless," some caregivers were uncertain about whether the individual for whom they provide care might feel this way but believed that this concept was probably true for many individual patients. Although many patients did not perceive much variability for themselves for this domain or many of its concepts, a few patients remarked on their current inability to control their feelings and behaviors and that improvement was needed in this area. Other patients noted the improvements they had experienced in this domain compared with when their schizophrenia was first diagnosed. In contrast, most caregivers believed that this domain changed considerably from day to day for their patient, whereas a few believed that their patient′s self-control was generally stable.

3.2.2.3 Emotional Regulation: Patients and caregivers expressed their understanding of this domain and the concepts within it. Patients′ interpretation of this domain largely included their overall feelings related to their hope and interest in their surroundings and future. The one item to which most patients could not fully relate and found difficult to answer was that related to feeling "full of confidence" and that "everything would be alright." Many patients commented that this item was too positive and even "grandiose," and some patients said that they would respond differently to each of the two concepts included in this single item. Similarly, caregivers felt that this item was unrealistic and overly positive. Many caregivers said that the behavior of their loved one with schizophrenia generally did not tend to vary as it related to this domain, noting that although the individuals′ mood may change (including emotional volatility), their feelings of hope and confidence were generally less variable. In contrast, many patients commented that they definitely had room for improvement relating to their emotions and hope for the future. In general, these patients were referring to their interest in their surroundings, level of confidence, and general happiness.

3.2.2.4 Physical Functioning: Both patients and caregivers interpreted this domain as relating to body image. Upon reading the domain name and first item ("I feel very comfortable with my body"), patients immediately expressed understanding for this domain as it related to perceptions of their body. Two of the items in this domain were unclear to some patients and some caregivers: "My body feels familiar, like it belongs to me" and "My body is a burden to me." Patients sometimes interpreted the former item literally, with responses such as "yes, of course, it does feel familiar, it′s mine." Some participants?both patients and caregivers?were unsure how to interpret the latter item. Participants generally understood the other two concepts in this domain, and some patients responded affirmatively to the item about feeling drained or exhausted. When asked about another way to interpret physical functioning (other than body image), a few patients provided examples, based on past delusional thoughts, such as seeing their body from a distance or feeling their body rise or move without intention. Based on an interpretation related to body image, neither patients nor caregivers believed that this domain was prone to frequent or large fluctuations based on their level of functioning.

3.2.2.5 Social Integration: Patients were able to describe and respond easily to most of the concepts in this domain, generally referring to their comfort being around and interacting with others in social settings. In addition, many caregivers noted that emotional volatility and hostility relating to this domain caused great challenges and limitations to the individuals′ social integration. The meaning of one of the items, "I perceive my environment as being changed, strange, and threatening," was not clear for some of the patients, making this item difficult to answer. Specifically, some patients were unsure about one or more of the three concepts included in this single item. For example, one patient could relate to his environment as being changed and strange but not threatening, whereas another patient could relate only to the word "threatening." Some caregivers also found the wording of this item to be confusing. Many patients believed that their overall functioning in this domain changed from time to time based on variations in their functioning and that this domain had room for improvement. Specifically, patients believed that they were more or less social at different times and that they could potentially be more engaged with others and their surroundings. For caregivers, this domain tended to change a great deal from day to day based on the individuals′ level of functioning.

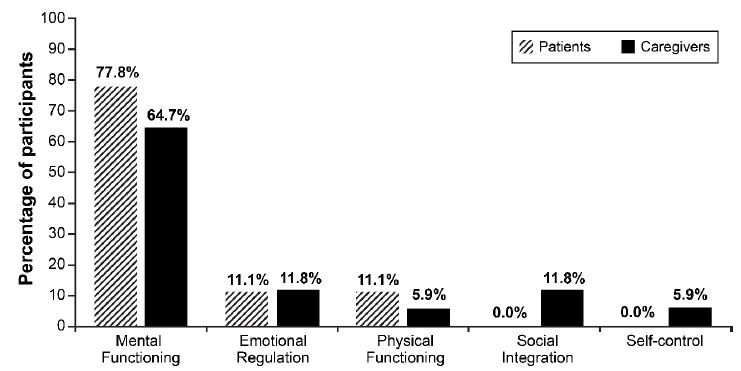

3.2.2.6 Relative Domain Importance: Figure 2 presents the proportion of patients and caregivers identifying each of the SWN-S domains as most important. To a considerable majority of both patients and caregivers, Mental Functioning was the most important domain in defining and contributing to patient HRQOL and functioning. Relatively small proportions of each sample identified the other SWN S domains as most important, and no patients identified Social Integration or Self-control as the most important domain.

Figure 2: Proportion of patients and caregivers ranking each SWN-S domain as most important.

Note: Three patients were not asked to provide importance rankings across the five SWN-S domains due to limited cognitive functioning and/or emotional distress. Thus, the patient sample size was 9, rather than 12, for this task.

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to explore and better understand patient and caregiver perspectives on some concepts associated with HRQOL and functioning as measured by the QLS and SWN-S. Overall, findings for the QLS suggest that mood, sense of purpose, motivation, and family and social relationships may be strong drivers of overall HRQOL and functioning (Intrapsychic Foundations and Interpersonal Relations domains). Findings for the SWN-S suggest that better mental or cognitive functioning (Mental Functioning domain), such as the ability to think clearly, may be most associated with overall HRQOL and functioning. However, although the English version of the SWN-S has been used in US populations of individuals with schizophrenia and is believed to include relevant content pertaining to patient functioning and HRQOL, in this study the measure was found to have some potential limitations, as some items were found to be unclear and confusing to both patients and caregivers. In general, congruence between patients and caregivers was observed in how they defined and described the concepts on both the QLS and SWN-S, as well as the relative importance of the domains on each measure. Patients and caregivers were also in general agreement on which domains were most likely to change (Intrapsychic Foundations and Interpersonal Relations from the QLS; Mental Functioning and Social Interaction from the SWN-S).

In generalizing across the QLS and SWN-S as these measures relate to HRQOL and functioning, patients and caregivers appeared to place the most importance on patients′ ability to think clearly (Mental Functioning, SWN-S), which in turn was believed to influence patients′ mood and motivation. Patients believed that their mood and motivation directly affected their comfort and their ability to engage socially. Moreover, these findings suggest that individuals with schizophrenia may very well be the most appropriate assessors of their current emotional state, level of motivation, or comfort with social interactions, even during periods of active symptoms and/or low insight. However, it must be noted that not all patients can accurately rate their level of mental functioning, even on "good" or high-functioning days. For instance, among the 12 patients interviewed in this study, 2 patients denied problems with their thinking when the interviewers suspected otherwise.

Although studies have evaluated HRQOL and functioning among patients with schizophrenia either subjectively or through a caregiver or clinician proxy and found disparate results [6, 7, 9, 10], incorporating both subjective and objective measurement as complementary assessments has been recommended [13]. The head to-head QUALIFY study incorporated both subjective and objective measures, employing both the QLS and the SWN-S to evaluate changes in HRQOL and functioning across 28 weeks of treatment with aripiprazole once monthly 400 mg (AOM 400) or paliperidone palmitate (PP) [14, 15]. In this study, both the QLS and SWN-S were found to be responsive measures, with patients showing improvements from baseline. The results from the QUALIFY study also support the findings of the current study: there was support for the sensitivity of the QLS Intrapsychic Foundations domain, with a significant difference between treatments at 28 weeks, favoring AOM 400 in comparison to PP [14].

The ability to evaluate domains on any given subjective measure and in comparison with caregiver ratings or, as in QUALIFY, clinician ratings is valuable. Patients are likely in the best position to evaluate their own mood state (e.g., if they say they are happy, then they are happy), whereas clinicians and caregivers may be best suited to evaluate the appropriateness of the patients′ expression of emotion and behavior, thus, their level of functioning from day to day. Furthermore, patients′ abilities to self-assess various aspects of their functioning, such as their cognitive function or their ability to form close relationships, may be hampered by limited and fluctuating levels of insight.

Some limitations must be considered when interpreting the results of this study. Qualitative methods such as those used in this study are often conducted for exploration and hypothesis generation. The small convenience samples included in the current study may not be representative of the larger population of patients with schizophrenia or their caregivers. As such, results from this study should be interpreted as directional and with caution in making broader generalizations. Moreover, participants were all residents of the US, and these results may not be generalizable to other countries or regions. Although cultural differences associated with mental illness do exist in many areas, it is unlikely that patient functioning levels vary significantly across culture, as the disease symptoms generally do not. Finally, the current study did not directly explore the relationship between patients′ HRQOL and functioning. Future research is needed to gain a better understanding and definition of the concepts that specifically contribute to patients′ HRQOL, as well as those related to the impact of HRQOL on patients′ real-world functioning. For example, understanding the relative importance and relationship among cognitive and emotional function, and how these specifically relate to motivation and social/familial interaction, could further assist in understanding the relationship between HRQOL and function. Gaining knowledge in this area could further assist in identifying the best instruments for measurement of these concepts and who is best (patients, clinicians, and/or caregivers) to complete them. Additionally, this knowledge could assist in the identification of HRQOL and functioning concepts that are most associated with treatment adherence and relapse.

5. Conclusions

The measurement of patient HRQOL and functioning and obtaining the patient perspective as it relates to subjective well-being is important in schizophrenia. The assessment of some types of patient functioning, however, may be best suited for clinician or caregiver evaluation. More research is needed to better understand the impact of patient HRQOL on daily functioning.

6. Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored by Lundbeck SAS and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and was performed under a research contract between Lundbeck SAS and RTI Health Solutions. Kate Lothman of RTI Health Solutions provided medical writing services, which were funded by Lundbeck SAS.

7. Conflicts of Interest

Maud Beillat is an employee of Lundbeck SAS. T. Michelle Brown and Dana B. DiBenedetti are employees of RTI Health Solutions. Dieter Naber is a paid consultant for Lundbeck SAS

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Washington: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

- Karow A, Wittmann L, et al. The assessment of quality of life in clinical practice in patients with schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 16 (2014): 185-195.

- Patel KR, Cherian J, et al. Schizophrenia: overview and treatment options. PT 39 (2014): 638-645.

- Boyer L, Millier A, et al. Quality of life is predictive of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 13 (2013): 15.

- Awad AG, Voruganti LN. Measuring quality of life in patients with schizophrenia: an update. Pharmacoeconomics 30 (2012): 183-195.

- Caqueo-Urizar A, Boyer L, et al. Subjective perceptions of cognitive deficits and their influences on quality of life among patients with schizophrenia. Qual Life Res 24 (2015): 2753-2760.

- Fervaha G, Takeuchi H, et al Determinants of patient-rated and clinician-rated illness severity in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 76 (2015): 924-930.

- Hayhurst KP, Massie JA, et al. Validity of subjective versus objective quality of life assessment in people with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 14 (2014): 365.

- Awadalla AW, Ohaeri JU, et al. Subjective quality of life of community living Sudanese psychiatric patients: comparison with family caregivers′ impressions and control group. Qual Life Res 14 (2005): 1855-1867.

- Crocker TF, Smith JK, et al. Family and professionals underestimate quality of life across diverse cultures and health conditions: systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 68 (2015): 584-595.

- Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, et al. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull 10 (1984): 388-398.

- Naber D. A self-rating to measure subjective effects of neuroleptic drugs, relationships to objective psychopathology, quality of life, compliance and other clinical variables. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 10 Suppl 3 (1995): 133-138.

- Tomotake M. Quality of life and its predictors in people with schizophrenia. J Med Invest 58 (2011): 167-174.

- Naber D, Hansen K, et al. QUALIFY: a randomized head-to-head study of aripiprazole once-monthly and paliperidone palmitate in the treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 168 (2015): 498-504.

- Naber D, Hansen K, et al. Improvement on secondary effectiveness measures with aripiprazole once-monthly versus paliperidone palmitate in QUALIFY, a head-to-head study. Abstract presented to the 28th ECNP Congress; 29 August-1 September 2015; Amsterdam.