National Trends in Utilization of Episiotomy and Factors Associated with High-Utilization Centers in the United States

Article Information

Ava D Mandelbaum1, Sarah E Rudasil1, Esteban Aguayo1, Elaine Chan1, Yas Sanaiha1, 2, Joshua G Cohen3, Peyman Benharash1, 2*

1Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Laboratories, Division of Cardiac Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, United States

2Division of General Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, United States

3Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, United States

*Corresponding author: Peyman Benharash, Division of Cardiac Surgery, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, CHS 62-249, 10833 Le Conte Ave, Los Angeles, CA, 90095, United States

Received: 19 June 2021; Accepted: 28 June 2021; Published: 16 July 2021

Citation:

Ava D Mandelbaum, Sarah E Rudasil, Esteban Aguayo, Elaine Chan, Yas Sanaiha, Joshua G Cohen, Peyman Benharash. National Trends in Utilization of Episiotomy and Factors Associated with High-Utilization Centers in the United States. Journal of Women’s Health and Development 4 (2021): 082-094.

Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Restrictive use of episiotomy has been recommended given potential risks of routine use. However, recent trends in episiotomy utilization and disparities in its use have not been examined at the national level in the United States. The present study aimed to characterize trends in episiotomy use and examine factors associated with high utilization.

Methods: The National Inpatient Sample database was queried to identify vaginal deliveries between 2005 and 2016. Patients were stratified based on ICD codes specifying episiotomy. Hospitals were classified as low, medium, and high utilization centers based on the annual number of episiotomies per delivery. Multivariable regressions were used to assess factors associated with episiotomy and high utilization centers.

Results: Of 32,975,144 vaginal delivery related hospitalizations, 12.9% underwent an episiotomy. Rates of episiotomy decreased from 19.5% in 2005 to 5.3% in 2016 (P<0.001). Episiotomy was associated with younger age (AOR= 0.96, P<0.001), lower Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (AOR= 0.79, P<0.001), Asian race (AOR= 1.81, P<0.001), private insurance (AOR= 1.32, P<0.001), highest income quartile (AOR= 1.15, P<0.001), as well as third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations (AOR= 2.10, P<0.001). High utilization centers were more likely to be urban, non-teaching institutions (AOR=3.54, P<0.001) with high-delivery volume (AOR=13.52, P<0.001) and large bed capacity (AOR=1.24, P<0.001).

Conclusions: National rates of episiotomy decreased significantly between 2005 and 2016. Several sociodemographic and hospital-level factors were associated with variation in utilization. Further study of targeted interventions through educational programs and quality benchmarks are needed to better define when episiotomy should be used in obstetrics.

Keywords

Episiotomy, Obstetric Surgical Procedure, National Inpatient Sample, NIS, Operative Delivery

Episiotomy articles Episiotomy Research articles Episiotomy review articles Episiotomy PubMed articles Episiotomy PubMed Central articles Episiotomy 2023 articles Episiotomy 2024 articles Episiotomy Scopus articles Episiotomy impact factor journals Episiotomy Scopus journals Episiotomy PubMed journals Episiotomy medical journals Episiotomy free journals Episiotomy best journals Episiotomy top journals Episiotomy free medical journals Episiotomy famous journals Episiotomy Google Scholar indexed journals Obstetric Surgical Procedure articles Obstetric Surgical Procedure Research articles Obstetric Surgical Procedure review articles Obstetric Surgical Procedure PubMed articles Obstetric Surgical Procedure PubMed Central articles Obstetric Surgical Procedure 2023 articles Obstetric Surgical Procedure 2024 articles Obstetric Surgical Procedure Scopus articles Obstetric Surgical Procedure impact factor journals Obstetric Surgical Procedure Scopus journals Obstetric Surgical Procedure PubMed journals Obstetric Surgical Procedure medical journals Obstetric Surgical Procedure free journals Obstetric Surgical Procedure best journals Obstetric Surgical Procedure top journals Obstetric Surgical Procedure free medical journals Obstetric Surgical Procedure famous journals Obstetric Surgical Procedure Google Scholar indexed journals National Inpatient Sample articles National Inpatient Sample Research articles National Inpatient Sample review articles National Inpatient Sample PubMed articles National Inpatient Sample PubMed Central articles National Inpatient Sample 2023 articles National Inpatient Sample 2024 articles National Inpatient Sample Scopus articles National Inpatient Sample impact factor journals National Inpatient Sample Scopus journals National Inpatient Sample PubMed journals National Inpatient Sample medical journals National Inpatient Sample free journals National Inpatient Sample best journals National Inpatient Sample top journals National Inpatient Sample free medical journals National Inpatient Sample famous journals National Inpatient Sample Google Scholar indexed journals NIS articles NIS Research articles NIS review articles NIS PubMed articles NIS PubMed Central articles NIS 2023 articles NIS 2024 articles NIS Scopus articles NIS impact factor journals NIS Scopus journals NIS PubMed journals NIS medical journals NIS free journals NIS best journals NIS top journals NIS free medical journals NIS famous journals NIS Google Scholar indexed journals Operative Delivery articles Operative Delivery Research articles Operative Delivery review articles Operative Delivery PubMed articles Operative Delivery PubMed Central articles Operative Delivery 2023 articles Operative Delivery 2024 articles Operative Delivery Scopus articles Operative Delivery impact factor journals Operative Delivery Scopus journals Operative Delivery PubMed journals Operative Delivery medical journals Operative Delivery free journals Operative Delivery best journals Operative Delivery top journals Operative Delivery free medical journals Operative Delivery famous journals Operative Delivery Google Scholar indexed journals Gynecologists articles Gynecologists Research articles Gynecologists review articles Gynecologists PubMed articles Gynecologists PubMed Central articles Gynecologists 2023 articles Gynecologists 2024 articles Gynecologists Scopus articles Gynecologists impact factor journals Gynecologists Scopus journals Gynecologists PubMed journals Gynecologists medical journals Gynecologists free journals Gynecologists best journals Gynecologists top journals Gynecologists free medical journals Gynecologists famous journals Gynecologists Google Scholar indexed journals Obstetricians articles Obstetricians Research articles Obstetricians review articles Obstetricians PubMed articles Obstetricians PubMed Central articles Obstetricians 2023 articles Obstetricians 2024 articles Obstetricians Scopus articles Obstetricians impact factor journals Obstetricians Scopus journals Obstetricians PubMed journals Obstetricians medical journals Obstetricians free journals Obstetricians best journals Obstetricians top journals Obstetricians free medical journals Obstetricians famous journals Obstetricians Google Scholar indexed journals Diagnoses articles Diagnoses Research articles Diagnoses review articles Diagnoses PubMed articles Diagnoses PubMed Central articles Diagnoses 2023 articles Diagnoses 2024 articles Diagnoses Scopus articles Diagnoses impact factor journals Diagnoses Scopus journals Diagnoses PubMed journals Diagnoses medical journals Diagnoses free journals Diagnoses best journals Diagnoses top journals Diagnoses free medical journals Diagnoses famous journals Diagnoses Google Scholar indexed journals geographic articles geographic Research articles geographic review articles geographic PubMed articles geographic PubMed Central articles geographic 2023 articles geographic 2024 articles geographic Scopus articles geographic impact factor journals geographic Scopus journals geographic PubMed journals geographic medical journals geographic free journals geographic best journals geographic top journals geographic free medical journals geographic famous journals geographic Google Scholar indexed journals obstetric practice articles obstetric practice Research articles obstetric practice review articles obstetric practice PubMed articles obstetric practice PubMed Central articles obstetric practice 2023 articles obstetric practice 2024 articles obstetric practice Scopus articles obstetric practice impact factor journals obstetric practice Scopus journals obstetric practice PubMed journals obstetric practice medical journals obstetric practice free journals obstetric practice best journals obstetric practice top journals obstetric practice free medical journals obstetric practice famous journals obstetric practice Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

1. Introduction

Episiotomy was historically recommended to facilitate delivery and improve maternal and neonatal outcomes alike. Despite absence of clear evidence supporting its use [1, 2], episiotomy was widely utilized in clinical practice to aid in vaginal deliveries. By 1979, approximately 61% of women who had a vaginal delivery underwent an episiotomy in the United States [3]. Over the past three decades, however, new evidence emerged on the adverse consequences of episiotomy. Several reports have challenged the role of episiotomy in vaginal deliveries, describing inferior maternal outcomes [1, 3-7]. Specifically, this technique has been associated with greater risks of perineal laceration, anal sphincter injury, pain, incontinence, and sexual dysfunction [1, 3, 8, 9]. In 2006, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published a practice bulletin advising against routine use of the procedure [2]. In 2018, ACOG reaffirmed restrictive over routine use of episiotomy for obstetric indications [10]. Subsequent reports have revealed a steady decline in the utilization of episiotomy following the initial publication of the ACOG recommendations on this topic in 2006 [2]. Although rates of episiotomy have decreased from 20.3% in 2003 to 9.4% in 2011 [11], significant hospital-level variations in the use of this procedure have been reported [5]. Recent trends in the utilization of episiotomy and disparities in its use have not been examined at the national level in the United States. The present study aimed to characterize temporal trends in the use of episiotomy across the United States. We further identified factors associated with high utilization of episiotomy.

2. Methods

2.1 Study design and population

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database was used to identify obstetric deliveries between 2005 and 2016. As part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), the NIS is an all-payer, inpatient database containing data on more than 7 million annual hospitalizations and is sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) [12]. NIS data are generated from hospital discharge abstracts via extracting diagnosis and procedure codes, as well as data on hospital bed size, urban versus rural location, teaching status, and region. Accurate discharge weights to estimate 97% of all US hospitalizations are obtained from an approximately 20% sample of all inpatient discharges. The study was deemed exempt from full review by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Los Angeles. Using previously validated ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic codes (Supplementary Table 1) [13], we identified deliveries from 2005 to 2016 in the NIS. Women who underwent a cesarean section were excluded from further sample.

Patients were stratified into two separate cohorts: 1) Episiotomy included delivery cohort (EIDC) and 2) No episiotomy included delivery cohort (nEIDC) based on whether episiotomy was used during vaginal delivery. Episiotomy was characterized as a binary variable and identified using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes (Supplementary Table 1). The type of episiotomy, such as midline versus mediolateral episiotomy, could not be identified in the NIS. Operative vaginal deliveries were distinguished using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes identifying forceps and vacuum-assisted procedures and dichotomized into EIDC or nEIDC. The presence of diagnoses codes for shoulder dystocia, fetal heart-rate abnormalities or fetal intolerance of labor was considered potential indications for episiotomy. Diagnoses of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations were identified in both cohorts to quantify the relationship between episiotomy and perineal injury.

Patient characteristics included maternal age, race, primary insurance status, and median household income quartile in the NIS. The Elixhauser Comorbidity Index was used to assess maternal burden of chronic conditions based upon 30 categories of comorbidity-based diagnosis codes [14]. Hospital characteristics were defined using the HCUP data dictionary and included location/teaching status (rural, urban/non-teaching, urban/teaching), geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), and bed size (small, medium, large) [12]. Hospital delivery volume was calculated as a continuous variable while volume tertiles (cut offs at 33rd and 66th percentiles) were created for each study year using the annual vaginal delivery caseload. The high-volume tertile had a median of 3,414 deliveries/year, while the low-volume tertile had median of 658 deliveries/year. Using a unique hospital identification number, hospital-level utilization was calculated as number of episiotomies per delivery for each year in each facility. Institutions were then characterized as low, medium, and high-utilization centers according to tertiles of normalized annual episiotomy utilization rate. The primary outcomes of this study were to examine trends in utilization and variables associated with use of episiotomy. Secondary outcomes included identification of factors associated with health centers noted to have higher utilization of episiotomy.

2.2 Statistical analysis

All sample sizes used in this study are national estimates given by Stata’s SVY command to account for the stratified cluster design of NIS and individual hospital’s discharge-level weights [12]. Patients with missing age, sex, mortality data, and costs were excluded from analysis. Due to the transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 coding in October 2015, the annual delivery and obstetric volume for 2015 was extrapolated linearly based on the first three quarters of the year. Univariate analysis comparing baseline demographics and outcomes were calculated using the Adjusted Wald or Kruskal-Wallis tests as appropriate. Temporal trends were assessed using Cuzick’s non-parametric test for trend [15]. Multivariable logistic regression models were developed to adjust for clinically relevant patient and hospital factors. Following a stepwise backward elimination, additional covariates were added based on clinical significance. Model selection was based on optimization of receiver operating curve (ROC) and Akaike’s and Bayesian Information Criteria. Regression models were reported with adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and with 95% confidence intervals. A P-value less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata software (Version 16.1, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

3. Results

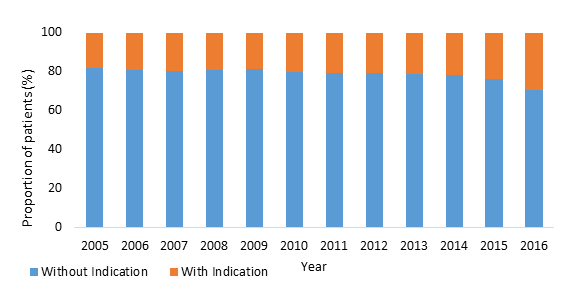

Of an estimated 32,975,144 vaginal delivery related hospitalizations during the study period, 4,240,933 (12.9%) underwent an episiotomy. The rate of episiotomy decreased significantly from 19.5% in 2005 to 5.3% in 2016 (P<0.001) (Figure 1). Diagnoses of shoulder dystocia, fetal intolerance of labor, and fetal heart rate abnormality was identified in 21.2% of women in the EIDC (Table 1). The proportion of women in the EIDC with these diagnoses increased from 18.2% in 2005 to 29.4% in 2016 (P<0.001). Fetal intolerance of labor and heart rate abnormalities were the most common diagnoses associated with an episiotomy (17.9%). In the EIDC, 21.3% underwent operative vaginal delivery, including either forceps (3.8%) or vacuum-assisted (17.6%) delivery. Univariate analysis of patient and hospital characteristics are shown in Table 1. On average, women in the EIDC were younger (26.8 years vs 27.5 years, P<0.001) and had a lower Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (0.12 vs 0.19, P<0.001) compared to women in the nEIDC. A higher proportion of women who underwent episiotomy were White (56.7% vs 52.2%, P<0.001), had private insurance (57.0% vs 48.4%, P<0.001), and belonged to the highest income quartile (25.6% vs 21.6%, P<0.001). Patients in the EIDC were more likely to be treated at urban, non-teaching (46.9% vs. 35.7%, P<0.001) and large bed size (60.2% vs 57.8%, P<0.001) centers compared to their nEIDC counterparts.

3.1 Sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with episiotomy

Multivariable logistic regression was used to account for differences in patient and hospital characteristics and to identify factors associated with episiotomy utilization in patients without codes for fetal complications (Table 2). After adjustment, younger age (AOR per year: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.95-0.97, P<0.001) and those with lower Elixhauser Comorbidity Index scores (AOR per year: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.78-0.81, P<0.001) remained significantly associated with increased likelihood of episiotomy utilization. Compared to White women, Black women had decreased odds (AOR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.54-0.59, P<0.001) of undergoing episiotomy, while Asian women had an increased risk of episiotomy (AOR: 1.81, 95% CI: 1.65-1.98, P<0.001). Private insurance (AOR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.18-1.48, P<0.001) and being in the highest income quartile (AOR: 1.15, 95% CI: 1.09-1.22, P<0.001) remained associated with episiotomy. The likelihood of receiving episiotomy decreased annually after 2005 (AOR: 0.65 relative to 2005, 95% CI: 0.56-0.69, P<0.001) (Figure 2). Episiotomy utilization was strongly associated with third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations (AOR: 2.10, 95% CI: 2.02-2.17, P<0.001) compared to women without perineal injury complications. Operative vaginal deliveries, including forceps (AOR: 6.11, 95% CI: 5.68-6.57, P<0.001) and vacuum-assisted (AOR: 4.75, 95% CI: 4.61-4.89, P<0.001) procedures, were significantly associated with performance of episiotomy.

3.2 Hospital level variations

To adjust for baseline patient and hospital differences, multivariable analysis was used to examine hospital-level variables associated with more frequent use of episiotomy at health centers (Table 3). Compared to urban teaching centers, high-utilization centers were more likely to be urban non-teaching institutions (AOR: 3.54, 95% CI: 2.68-4.67, P<0.001). Medical centers with large bed capacity (AOR: 1.24, 95% CI: 0.96-1.60, P<0.001) and high-delivery volume (AOR: 13.52, 95% CI: 10.63-15.98, P<0.001) were significantly associated with high-utilization centers. In addition, compared to the Midwestern region, hospitals located in the Northeast (AOR: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.06-2.02, P=0.021) and South (AOR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.00-1.78, P=0.057) were associated with high utilization.

Figure 1: National utilization of episiotomy in the United States between 2005 and 2016.

|

nEIDC (N=28, 734, 211) |

EIDC (N=4, 240, 933) |

P-value |

|

|

Age (years ± SD) |

27.8 ± 5.7 |

26.7 ± 6.1 |

<0.001 |

|

Elixhauser Index (score ± SD) |

0.19 ± 0.44 |

0.12 ± 0.35 |

<0.001 |

|

Indication of Episiotomy (%) |

13.9 |

21.2 |

<0.001 |

|

Shoulder Dystocia |

1.9 |

3.3 |

|

|

Fetal Complications |

12.0 |

17.9 |

|

|

Operative Delivery (%) |

<0.001 |

||

|

Vacuum |

4.2 |

17.6 |

|

|

Forceps |

0.7 |

3.8 |

|

|

Perineal Laceration |

<0.001 |

||

|

3rd degree |

1.9 |

5.4 |

|

|

4th degree |

0.4 |

2.1 |

|

|

Age Range (%) |

<0.001 |

||

|

<21 |

12.7 |

18.2 |

|

|

21-25 |

25.9 |

25.3 |

|

|

26-30 |

29.0 |

28.0 |

|

|

31-35 |

22.1 |

19.9 |

|

|

>35 |

10.3 |

8.6 |

|

|

Elixhauser Range (%) |

<0.001 |

||

|

<1 |

84.7 |

89.4 |

|

|

1-2 |

12.8 |

9.4 |

|

|

2-3 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

|

|

>3 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

|

|

Race (%) |

<0.001 |

||

|

White |

52.2 |

56.7 |

|

|

Black |

14.2 |

8.1 |

|

|

Hispanic |

23.0 |

21.0 |

|

|

Asian |

57.0 |

8.4 |

|

|

Other * |

5.6 |

5.8 |

|

|

Insurance Coverage (%) |

<0.001 |

||

|

Medicare |

0.6 |

0.5 |

|

|

Medicaid |

44.8 |

36.7 |

|

|

Private |

48.4 |

57.0 |

|

|

Other † |

3.2 |

6.0 |

|

|

Income Quartile (%) |

<0.001 |

||

|

<25th |

28.2 |

24.1 |

|

|

25th-50th |

25.5 |

24.6 |

|

|

50th-75th |

24.7 |

25.8 |

|

|

>75th |

21.6 |

25.6 |

|

|

Hospital Region (%) |

<0.001 |

||

|

Northeast |

15.9 |

16.7 |

|

|

Midwest |

22.1 |

21.6 |

|

|

South |

36.8 |

37.5 |

|

|

West |

25.2 |

24.2 |

|

|

Teaching Status (%) |

<0.001 |

||

|

Rural, non-teaching |

11.0 |

10.8 |

|

|

Urban, non-teaching |

35.7 |

46.9 |

|

|

Urban, teaching |

53.3 |

42.2 |

|

|

Hospital Bed Size (%) |

<0.001 |

||

|

Small |

14.3 |

11.9 |

|

|

Medium |

27.9 |

28.1 |

|

|

Large |

57.8 |

60.2 |

|

* indicates a combined group of Asian, Native American, and other races as defined by NIS

† indicates a combined insurance status including self-pay, uninsured, and other

Table 1: Comparison of patient and hospital characteristics for the episiotomy (EIDC) and no episiotomy delivery (nEIDC) cohorts.

|

AOR |

95% CI |

P-value |

|

|

Age (per year) |

0.96 |

0.95-0.97 |

<0.001 |

|

Elixhauser Index (per unit increase) |

0.79 |

0.78-0.81 |

<0.001 |

|

Race |

|||

|

White |

Reference |

||

|

Black |

0.56 |

0.54-0.59 |

<0.001 |

|

Hispanic |

0.93 |

0.87-0.98 |

0.017 |

|

Asian |

1.81 |

1.65-1.98 |

<0.001 |

|

Insurance Coverage |

|||

|

Medicare |

Reference |

||

|

Medicaid |

0.92 |

0.81-1.02 |

0.135 |

|

Private |

1.32 |

1.18-1.48 |

<0.001 |

|

Income Quartile |

|||

|

<25th |

Reference |

||

|

25th-50th |

1.02 |

0.98-1.06 |

0.262 |

|

50th-75th |

1.09 |

1.03-1.14 |

0.002 |

|

>75th |

1.15 |

1.09-1.22 |

<0.001 |

|

Hospital Region |

|||

|

Midwest |

Reference |

||

|

Northeast |

1.31 |

1.18-1.43 |

<0.001 |

|

South |

1.25 |

1.16-1.35 |

<0.001 |

|

West |

0.99 |

0.89-1.09 |

0.823 |

|

Teaching Status |

|||

|

Urban, teaching |

Reference |

||

|

Urban, non-teaching |

1.53 |

1.40-1.68 |

<0.001 |

|

Rural, non-teaching |

1.10 |

0.99-1.23 |

0.067 |

|

Bed size |

|||

|

Small |

Reference |

||

|

Medium |

1.07 |

0.98-1.18 |

0.127 |

|

Large |

1.06 |

0.97-1.16 |

0.160 |

|

Delivery Volume |

|||

|

Low |

Reference |

||

|

Medium |

1.02 |

0.89-1.12 |

0.959 |

|

High |

1.04 |

0.94-1.16 |

0.423 |

|

Operative Vaginal Delivery |

|||

|

Forceps |

6.11 |

5.68-6.57 |

<0.001 |

|

Vacuum |

4.75 |

4.61-4.89 |

<0.001 |

|

Perineal Laceration |

|||

|

3rd/4th Degree Tear |

2.10 |

2.02-2.17 |

<0.001 |

|

Year of Delivery |

|||

|

2005 |

Reference |

||

|

After 2005 (per year) |

0.65 |

0.56-0.69 |

<0.001 |

Table 2: Factors associated with episiotomy performed without documented indication on multivariable analysis.

Figure 2: Adjusted odds ratios of factors associated with episiotomy.

|

AOR |

95% CI |

P-value |

|

|

Hospital Region |

|||

|

Midwest |

Reference |

||

|

Northeast |

1.46 |

1.06-2.02 |

0.021 |

|

South |

1.33 |

1.00-1.78 |

0.057 |

|

West |

0.65 |

0.48-0.88 |

0.005 |

|

Teaching Status |

|||

|

Urban, teaching |

Reference |

||

|

Urban, non-teaching |

3.54 |

2.68-4.67 |

<0.001 |

|

Rural, non-teaching |

0.59 |

0.42-0.83 |

<0.001 |

|

Bed-size |

|||

|

Small |

Reference |

||

|

Medium |

1.22 |

0.95-1.58 |

0.123 |

|

Large |

1.24 |

0.96-1.60 |

<0.001 |

|

Delivery Volume |

|||

|

Low |

Reference |

||

|

Medium |

5.03 |

3.98-6.35 |

<0.001 |

|

High |

13.52 |

10.63-15.98 |

<0.001 |

|

Year of Delivery |

|||

|

2005 |

Reference |

||

|

After 2005 (per year) |

1.17 |

0.87-1.57 |

0.196 |

Table 3: Factors associated with high-utilization hospitals on multivariable analysis.

4. Discussion

While routine episiotomy has been historically utilized in obstetric practice, current evidence demonstrates no clear benefits in women who undergo the procedure without a clinical indication [1, 3]. In this study, we aimed to evaluate recent trends in utilization and factors associated with episiotomy in the United States. We further aimed to identify hospital-level factors associated with high utilization. With analysis of the NIS, we found that the rate of episiotomy continued to decline significantly over the decade long study period. In 2016, approximately 5% of women undergoing vaginal deliveries received an episiotomy, down from 20% in 2005. Performance of episiotomy varied across sociodemographic groups and hospital-level variables. High-utilization centers in the United States were more likely to be urban, non-teaching institutions with high-delivery volume and large bed capacity. Prior literature has reported a significant decline in use of routine episiotomy [3-5, 11, 16].

Our results are consistent with these studies and demonstrate the continued decline in use of episiotomy at a national level in the United States. This decrease may reflect widespread adoption of clinical practice recommendations, first published in 2006 by ACOG [2]. Among women who underwent an episiotomy, 86% of these patients did not have an associated diagnosis of shoulder dystocia, fetal intole-rance of labor, or fetal heart rate abnormalities. While this observation may reflect inaccurate coding practices, slow diffusion of guidelines or resistance to change among established obstetricians may be present [3].

Several patient characteristics, including age, race, insurance status, and income level, were found to be associated with episiotomy utilization. Consistent with prior work, younger age, lower Elixhauser comorbidity scores, White and Asian race, private insurance, and high-income levels were significantly associated with increased use of episiotomy [17-24]. While the mean difference in maternal age between cohorts may lack clinical significance, younger maternal age remained clearly associated with episiotomy utilization after adjustment for patient and hospital characteristics. Younger women with fewer comorbidities are generally more likely to be nulliparous and thus may be at higher risk for episiotomy utilization [17].

Furthermore, racial variability has been reported with higher incidences of episiotomy in women of non-Black race, particularly Asian women [18-20]. Grobman et al. found both higher rates of episiotomy and more severe perineal laceration grades in Asian women compared to other races [20]. Physicians may be more likely to consider an episiotomy necessary for certain racial groups given perception of increased risk of perineal trauma for that population. Furthermore, a prior study found private insurance coverage was associated with higher rates of several obstetric interventions, including episiotomy [23]. These findings have important implications in shaping healthcare policies and guiding appropriate patient-centered decisions in maternal care. To begin targeted reductions in routine episiotomy, it is necessary to understand the patient population at risk of receiving an episiotomy without a clinical indication.

Prior literature has identified several adverse outcomes associated with performance of episiotomy [1, 24, 25]. This analysis found episiotomy was overall associated with a significant increase in the incidence of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations. Several reports have observed similar or even higher rates of severe perineal trauma [25-29]. Using a multi-institutional database, Landy et al. reported more than 62% of women who had third- and fourth-degree lacerations received episiotomies [26]. However, recent evidence has also emerged on the protective association between mediolateral episiotomy and obstetric anal sphincter injury in operative vaginal deliveries [30]. While our findings provide further support for a general restricted use of episiotomy in national obstetric practice, future prospective studies are needed to explore more specific guidelines for episiotomy utilization among various types of delivery.

Although previous studies have reported hospital-level factors associated with increased episiotomy utilization, this analysis includes data on a national level in the United States [4, 11]. We utilized a measure that involved calculation of the ratio of total episiotomies to total deliveries per year to more accurately assess utilization across hospitals [31, 32]. Using this measure, we found urban non-teaching designation, high-delivery volume, and large hospital size were significantly associated with high-utilization centers. Kozhimannil and colleagues similarly found urban nonteaching status to be a strong predictor of episiotomy following the issuance of the ACOG recommendations [11]. Access to emerging research, available resources, differences in hospital culture, and provider experience levels likely contribute to the disparity in episiotomy use between teaching and nonteaching centers. Several studies have also attributed variation in episiotomy utilization to differences in physician decision-making practices and number of years in practice [33, 34]. It is plausible that episiotomies may be utilized to accelerate labor or manage clinical capacity strain, particularly in hospitals with high-delivery volume, thus contributing to the observed increase in episiotomy rates. These factors demonstrate the importance of both hospital- and physician-level interventions to help improve future maternal outcomes. Quality benchmarks and targeted education programs may be required at high utilization centers and with specific patient populations to ensure restrictive episiotomy practice is used.

This study has limitations inherent to its retrospective nature. We are limited by the accuracy of data and potential variation in coding practices within the NIS database. The administrative methodology of the NIS limits the ability to account for several maternal and fetal factors that may influence clinical decision-making regarding episiotomy use, such as history of prior episiotomy, fetal birthweight, gestational age, and number of prior births. Deliveries that take place at home and at birthing centers were not included in this analysis. Furthermore, we were unable to capture data on individual physician episiotomy rates, patient preferences regarding the procedure, or the type of episiotomy performed (midline versus mediolateral). Despite these limitations, we used validated methodology and the largest available inpatient dataset to examine national trends and outcomes over a decade long study period.

5. Conclusion

In summary, national rates of episiotomy in the United States decreased significantly following evidence-based recommendations against routine use of the procedure. Episiotomy was associated with severe perineal lacerations. Several patient sociodemographic factors, including race, income, and insurance coverage, were associated with individual variation in performance of episiotomy. Hospital-level factors, including non-teaching status, urban location, and high-delivery volume, were associated with high-utilization centers. Further study of targeted interventions through educational programs and quality benchmarks are needed to ensure restrictive over routine use of episiotomy in obstetrical care in the United States.

Acknowledgements and Disclosures

There has been no financial assistance with the project.

Sources of Funding

None

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this manuscript.

References

- Hartmann K, Viswanathan M, Palmieri R, et al. Outcomes of routine episiotomy: a systematic review. JAMA 293 (2005): 2141-2148.

- American College of Obstetricians-Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin: episiotomy: clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists: Number 71, April 2006. Obstet Gynecol. 107 (2006): 957-962.

- Elizabeth A Frankman, Li Wang, Clareann H Bunker, et al. Episiotomy in the United States: has anything changed?. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200 (2009): 573e1-e7.

- Bansal R, Tan W, Ecker J, et al. Is there a benefit to episiotomy at spontaneous vaginal delivery? A natural experiment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 175 (1996): 897-901.

- Alexander M Friedman, Cande V Ananth, Eri Prendergast, et al. Variation in and factors associated with use of episiotomy. JAMA 313 (2015): 197-199.

- Goldberg J, Holz D, Hyslop T, et al. Has the use of routine episiotomy decreased? Examination of episiotomy rates from 1983-2000. Obstet Gynecol 99 (2002): 395-400.

- Ecker J, Tan W, Bansal R, et al. Is there a benefit to episiotomy at operative vaginal delivery? Observations over ten years in a stable population. Am J Obstet Gynecol 176 (1997): 411-414.

- Dogan B, Gün ?, Özdamar Ö, et al. Long-term impacts of vaginal birth with mediolateral episiotomy on sexual and pelvic dysfunction and perineal pain. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 30 (2017): 457-460.

- Dudding TC, Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA. Obstetric anal sphincter injury: incidence, risk factors, and management. Ann Surg 247 (2008): 224-237.

- American College of Obstetricians-Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin: Prevention and Management of Obstetric Lacerations at Vaginal Delivery: Number 198, Sep 2006. Obstet Gynecol 132 (2018): e87-e102.

- Kozhimannil KB, Karaca-Mandic P, Blauer-Peterson CJ, et al. Uptake and utilization of practice guidelines in hospitals in the United States: the case of routine episiotomy. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 43 (2017): 41-48.

- HCUP-US NIS Overview. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2020).

- Kuklina E V, Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, et al. An enhanced method for identifying obstetric deliveries: implications for estimating maternal morbidity. Matern Child Health J 12 (2008): 469-477.

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity Measures for Use with Administrative Data. Med Care 36 (1998): 8-27.

- Cuzick J. A Wilcoxon-type test for trend. Stat Med 4 (1985): 87-90.

- Shen YC, Sim WC, Caughey AB, et al. Can major systematic reviews influence practice patterns? A case study of episiotomy trends. Arch Gynecol Obstet 288 (2013): 1285-1293.

- Hueston WJ. Factors associated with the use of episiotomy during vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol 87 (1996): 1001-1005.

- de Silva KL, Tsai PJ, Kon LM, et al. Third- and fourth-degree perineal injury after vaginal delivery: does race make a difference?. Hawaii J Med Public Health 73 (2014): 80-83.

- Goldberg J, Hyslop T, Tolosa JE, et al. Racial differences in severe perineal lacerations after vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 188 (2003): 1063-1067.

- William A Grobman, Jennifer L Bailit, Madeline Murguia Rice, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol 125 (2015): 1460-1467.

- Wheeler TL, Richter HE. Delivery method, anal sphincter tears and fecal incontinence: new information on a persistent problem. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 19 (2007): 474-479.

- D'Souza JC, Monga A, Tincello DG. Risk factors for perineal trauma in the primiparous population during non-operative vaginal delivery. Int Urogynecol J 31 (2020): 621-625.

- Williams A, Gonzalez B, Fitzgerald C, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Perineal Lacerations in a Diverse Urban Healthcare System. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 25 (2019): 15-21.

- Katy B Kozhimannil, Tetyana P Shippee, Olusola Adegoke, et al. Trends in hospital-based childbirth care: the role of health insurance. Am J Manag Care 19 (2013): e125-e132.

- Jiang H, Qian X, Carroli G, et al. Selective versus routine use of episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2 (2017): CD000081.

- Landy HJ, Laughon SK, Bailit JL, et al. Characteristics associated with severe perineal and cervical lacerations during vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol 117 (2011): 627-635.

- Yamasato K, Kimata C, Huegel B, et al. Restricted episiotomy use and maternal and neonatal injuries: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 294 (2016): 1189-1194.

- Steiner N, Weintraub AY, Wiznitzer A, et al. Episiotomy: the final cut?. Arch Gynecol Obstet 286 (2012): 1369-1373.

- Stedenfeldt M, Pirhonen J, Blix E, et al. Episiotomy characteristics and risks for obstetric anal sphincter injuries: a case-control study. BJOG 119 (2012): 724-730.

- Muraca GM, Liu S, Sabr Y, et al. Episiotomy use among vaginal deliveries and the association with anal sphincter injury: a population-based retrospective cohort study. CMAJ 191 (2019): E1149-E1158.

- Kozhimannil KB, Arcaya MC, Subramanian SV. Maternal clinical diagnoses and hospital variation in the risk of cesarean delivery: analyses of a national US hospital discharge database. PLoS Med 11 (2014): e1001745.

- Armstrong J, Kozhimannil K, McDermott P, et al. Comparing variation in hospital rates of cesarean delivery among low-risk women using three different measures. Am J Obstet Gynecol 214 (2016): 153- 163.

- Howden N, Weber A, Meyn L. Episiotomy use among residents and faculty compared with private practitioners. Obstet Gynecol 103 (2004): 114-118.

- Goode KT, Weiss PM, Koller C, et al. Episiotomy rates in private vs. resident service deliveries: a comparison. J Reprod Med 51 (2006): 190-192.

Supplementary

|

ICD-9 |

ICD-10 |

|

|

All deliveries |

V27x, 650, 72x, 73.22, 73.5x, 73.6, 73.8, 73.9x, 74.x |

O80, O82, Z37.x, 10D0x, 10E0XZZ |

|

Episiotomy |

73.6, 72.1, 72.21, 72.31, and 72.71 |

0W8NXZZ |

|

Shoulder Dystocia |

660.4x |

O66.0 |

|

Fetal Complications |

768.x, 656.3x, 659.7x |

O68, O76, O77.x |

|

Perineal Laceration |

664.x (exclude .x4) |

O70.x |

Supplementary Table 1: ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes used to identify study population and patient variables.