Incidence of and Risk Factors for Missing Events Due to Wandering in Community-Dwelling Older Adults with Dementia

Article Information

Seungwon Jeong1,2*, Takao Suzuki1,3, Kiyoko Miura1, Takashi Sakurai1

1Department of Social Science, National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Aichi, Japan

2Department of Community Welfare, Niimi University, Okayama, Japan

3Institute for Gerontology, J. F. Oberlin University, Tokyo, Japan

*Corresponding Author: Seungwon Jeong, Department of Social Science, National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Aichi, Japan

Received: 27 April 2023; Accepted: 05 May 2023; Published: 19 May 2023

Citation:

Seungwon Jeong, Takao Suzuki, Kiyoko Miura, Takashi Sakurai. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Missing Events Due To Wandering in Community-Dwelling Older Adults With Dementia. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Disorders. 7 (2023): 38-45

Share at FacebookAbstract

The burden of missing incidents due to wandering with dementia is not only on the patient but also on their family, neighbors, and community. In this study, we conducted a non-randomized prospective one-year followup cohort study based on symptom registration with missing cases due to wandering with dementia as the endpoint. The incidence and recurrence rates of missing events were calculated. Furthermore, analysis of variance and logistic regression analysis were performed to clarify the risk factors associated with the missing event. Among the 236 patients with dementia enrolled, 65 (27.5%) had a previous missing event at baseline. Of the 65 patients with dementia who had a previous missing event at baseline, 28 had a missing event during the oneyear follow-up period (recurrence rate of 43.1%). Of the 171 who did not have a previous missing event at baseline, 23 had a missing event during the one-year follow-up period (incidence rate of 13.5%). Prevention of missing events requires focused attention on changes in the Mini-Mental State Examination, Dementia Behavior Disturbance Scale, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale scores, and the development of a social environment for supporting family caregivers.

Keywords

wandering, missing, community-dwelling, dementia

wandering articles, missing articles, community-dwelling articles, dementia articles

wandering articles wandering Research articles wandering review articles wandering PubMed articles wandering PubMed Central articles wandering 2023 articles wandering 2024 articles wandering Scopus articles wandering impact factor journals wandering Scopus journals wandering PubMed journals wandering medical journals wandering free journals wandering best journals wandering top journals wandering free medical journals wandering famous journals wandering Google Scholar indexed journals missing articles missing Research articles missing review articles missing PubMed articles missing PubMed Central articles missing 2023 articles missing 2024 articles missing Scopus articles missing impact factor journals missing Scopus journals missing PubMed journals missing medical journals missing free journals missing best journals missing top journals missing free medical journals missing famous journals missing Google Scholar indexed journals community-dwelling articles community-dwelling Research articles community-dwelling review articles community-dwelling PubMed articles community-dwelling PubMed Central articles community-dwelling 2023 articles community-dwelling 2024 articles community-dwelling Scopus articles community-dwelling impact factor journals community-dwelling Scopus journals community-dwelling PubMed journals community-dwelling medical journals community-dwelling free journals community-dwelling best journals community-dwelling top journals community-dwelling free medical journals community-dwelling famous journals community-dwelling Google Scholar indexed journals dementia articles dementia Research articles dementia review articles dementia PubMed articles dementia PubMed Central articles dementia 2023 articles dementia 2024 articles dementia Scopus articles dementia impact factor journals dementia Scopus journals dementia PubMed journals dementia medical journals dementia free journals dementia best journals dementia top journals dementia free medical journals dementia famous journals dementia Google Scholar indexed journals behavior articles behavior Research articles behavior review articles behavior PubMed articles behavior PubMed Central articles behavior 2023 articles behavior 2024 articles behavior Scopus articles behavior impact factor journals behavior Scopus journals behavior PubMed journals behavior medical journals behavior free journals behavior best journals behavior top journals behavior free medical journals behavior famous journals behavior Google Scholar indexed journals Lifestyle articles Lifestyle Research articles Lifestyle review articles Lifestyle PubMed articles Lifestyle PubMed Central articles Lifestyle 2023 articles Lifestyle 2024 articles Lifestyle Scopus articles Lifestyle impact factor journals Lifestyle Scopus journals Lifestyle PubMed journals Lifestyle medical journals Lifestyle free journals Lifestyle best journals Lifestyle top journals Lifestyle free medical journals Lifestyle famous journals Lifestyle Google Scholar indexed journals disorders articles disorders Research articles disorders review articles disorders PubMed articles disorders PubMed Central articles disorders 2023 articles disorders 2024 articles disorders Scopus articles disorders impact factor journals disorders Scopus journals disorders PubMed journals disorders medical journals disorders free journals disorders best journals disorders top journals disorders free medical journals disorders famous journals disorders Google Scholar indexed journals Geriatric Depression Scale articles Geriatric Depression Scale Research articles Geriatric Depression Scale review articles Geriatric Depression Scale PubMed articles Geriatric Depression Scale PubMed Central articles Geriatric Depression Scale 2023 articles Geriatric Depression Scale 2024 articles Geriatric Depression Scale Scopus articles Geriatric Depression Scale impact factor journals Geriatric Depression Scale Scopus journals Geriatric Depression Scale PubMed journals Geriatric Depression Scale medical journals Geriatric Depression Scale free journals Geriatric Depression Scale best journals Geriatric Depression Scale top journals Geriatric Depression Scale free medical journals Geriatric Depression Scale famous journals Geriatric Depression Scale Google Scholar indexed journals Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale articles Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale Research articles Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale review articles Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale PubMed articles Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale PubMed Central articles Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale 2023 articles Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale 2024 articles Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale Scopus articles Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale impact factor journals Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale Scopus journals Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale PubMed journals Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale medical journals Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale free journals Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale best journals Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale top journals Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale free medical journals Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale famous journals Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale Google Scholar indexed journals scores for Barthel index articles scores for Barthel index Research articles scores for Barthel index review articles scores for Barthel index PubMed articles scores for Barthel index PubMed Central articles scores for Barthel index 2023 articles scores for Barthel index 2024 articles scores for Barthel index Scopus articles scores for Barthel index impact factor journals scores for Barthel index Scopus journals scores for Barthel index PubMed journals scores for Barthel index medical journals scores for Barthel index free journals scores for Barthel index best journals scores for Barthel index top journals scores for Barthel index free medical journals scores for Barthel index famous journals scores for Barthel index Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

1. Introduction

Populations are aging globally, and the number of older adults with dementia is increasing. About 50 million people worldwide have dementia, with nearly 10 million new cases being diagnosed every year [1] . Japan has the highest life expectancy in the world. The aging rate was 28.1% in 2018, and 15.5% of the 65 and older population had dementia in 2015. The number of people with dementia will continue to increase.

Wandering in the context of dementia has been seen as a syndrome of frequent, repetitive, seemingly aimless, typically temporally, and spatially-disoriented ambulation [2,3] . Eventually, 60%-80% of people with dementia will wander [4,5]. Previous studies have determined some risk factors of wandering to impair certain brain functions, spatial memory, visuospatial processes or executive functions [6], and severity of dementia [7,8]. However, it is still unclear how dementia and a decline in cognitive function are linked to missing incidents.

According to the National Police Agency in Japan, the number of missing incidents due to dementia increased from 9,607 in 2012 to 16,927 in 2018. Also, wandering due to dementia has sometimes led to fatal accidents [9,10].

A particular note is that many patients with dementia live with their families in their homes of their community. Therefore, when wandering or missing incidents occur in the community, the burden is not only on the person with dementia but also on their family, neighbors, and community [11]. However, not enough studies have thoroughly examined the extent to which dementia-related wandering and missing incidents occur. Moreover, in Japan, we are in an era where the responsibility lies not only within the family but also in the entire community and society. The moral responsibility of keeping everyone safe and avoiding unwanted accidents caused by wandering older people with dementia remains essential.

Therefore, we conducted a prospective cohort study based on symptom registration with missing events due to wandering as the endpoint. We calculated the incidence and recurrence rate of missing events during the follow-up and then analyzed which factors could more clearly predict the incidence of missing events.?

2. Methods

Study design: Non-randomized prospective cohort study

Study participants: Of the patients with dementia who visited the Center for Comprehensive Care and Research on Memory Disorders at the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology for their first consultation between April 2017 and March 2018, we investigated all those who (1) could understand the Japanese language, (2) were accompanied by a caregiver, and (3) provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Informed consent to participate in the study was received from 490 pairs of patients and their caregivers.

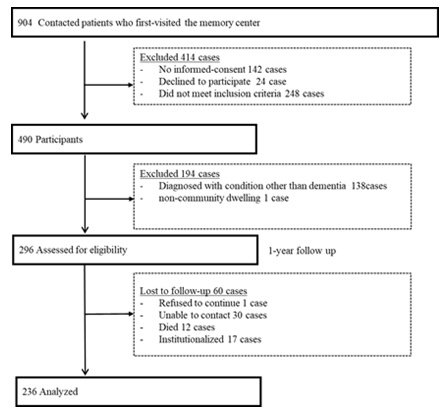

The 138 were excluded for not having dementia, and one for living in a nursing home. During the follow-up, 60 participants dropped out. We could not determine if there were missing events in 31 who could not be traced (refused tracing); 12 died; 17 were admitted to a nursing home. Thus, 236 pairs participated in the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Study participants

Definition and assessment of “missing” events:

The word “wandering” is widely used to cover various actions and is often seen as a type of disturbed behavior [12]. Although “a syndrome of dementia-related locomotion behavior” was proposed as the definition of wandering in 2007 [3]. However, there is still a lack of consensus. In recent years, this term has often been confounded with “missing” and “getting lost.”

In the present study, we use “missing” and limited our investigations to missing events due to dementia-related wandering.

We used the following references to determine “missing”. (1) the Algase wandering scale and conceptual domain [13], (2) the wandering questionnaire by Houston et al. [14], (3) the Awata group episodes of dementia wandering in Japan, and (4) the missing incidents conceptual model by Rowe et al. [15]. Then, we adopted the main idea commonly used in the four references (Table 1).

In this study, if the following four conditions were confirmed, it was considered a missing event due to wandering: (1) The patient was outside and did not know where he/she was; (2) the patient went out and did not return within the expected time; (3) the patient went out at night while you were sleeping (sometimes); (4) the patient was agitated and went out (sometimes).

Table 1: Questions for assessment of missing events

|

Questions |

Algase wandering scale and conceptual domain |

Houston et al. wandering questionnaire |

Awata group episodes |

Rowe et al. missing incidents conceptual model |

|

|

1 |

The patient was outside and did not know where he/she was |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

2 |

The patient went out and did not return within the expected time |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

3 |

The patient went out at night while you were sleeping (sometimes) |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

4 |

The patient was agitated and went out (sometimes) |

? |

? |

? |

?: Episodes used in references for assessing wandering

Reliability of variables used in the analysis:

A questionnaire survey and an interview were conducted on patients and their families or caregivers at the time of registration. Data was collected from basic attributes, medical information, a sense of family burden and others. To test the reliability of a self-reported questionnaire, we conducted a reliability test using the questionnaire responses and interview responses; as a result, consistency was given 81.4%.

A follow-up study was performed a year after registration, and mail surveys were administered to ascertain the occurrence and frequency of missing events during the follow-up. Of those surveyed in the follow-up, 53 (95% interval ±0.05% acceptable error range, estimated sample size) randomly selected were interviewed for a test of reliability in a self-reported questionnaire, with an 84.9% consistency. Generally, high reliability was observed for questionnaire responses.

The following information was obtained at baseline:

(1) Diagnosis of dementia

(2) Basic attributes: sex, age, years of education, living alone, and financial difficulties

(3) Medical information about patients: body mass index (BMI), scores for Barthel index (1-100), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; 0-30), Dementia Behavior Disturbance Scale (DBD; 0-112), Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS; 0-70), Raven's Colored Progressive Matrices (RCPM; 0-36), Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB; 0-18), geriatric syndrome (0-24), vitality index (0-10), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; 1-15).

(4) Lifestyle: alcohol consumption, smoking, sleep disorders, absence of exercise.

(5) Information about family caregivers: sex, age, years of education, employment (yes or no), providing care every day (yes or no), availability of other caregivers (yes or no), the experience of caregiving for dementia patients (yes or no), attended a seminar for caregiving to dementia patient (yes or no), poor physical health (yes or no), GDS (1-15), the Japanese version of the Zarit caregiver burden interview (J-ZBI) [16] score (0-88) (Table 2).

Statistical analysis:

The incidence rate and recurrence rate of missing events were calculated.

Patients' basic and medical information were shown at baseline and at a one-year follow-up.

Patients were divided into those who did not go missing (no missing event), those who went missing for the first time (incidence), and those who had a recurrent missing event (recurrence) during the year of follow-up.

Analysis of variance and post-hoc tests or χ2 test, Fisher exact test were performed to determine differences between baseline and one-year follow-up.

Univariate and multivariate logistic analyses were performed to find the incidence of missing events during follow-up and related variables. Variables that were statistically significant in the univariate logistic analysis were used as variables in the multivariate logistic analysis.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the risk factors of incidence and recurrence of missing events during the one-year follow-up period as the dependent variable and medical and social factors as independent variables. We controlled for the patients' sex, age, years of education, and financial difficulties. Statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS ver.25 (Chicago, IL, USA). A two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations:

This study was planned according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical standards declared in ethical guidelines for medical research involving human subjects, and the study design was approved by the Ethics and Conflicts of Interest Committee of the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (No. 977-2). Approval Date: 29 March 2017.

3. Results

Incidence and recurrence rate of missing events

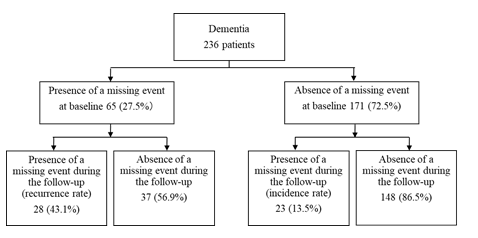

Among the 236 patients with dementia, 65 (27.5%) had a previous missing event at baseline, and 171 (72.5%) did not. Including both those with and without a previous missing event at baseline, 51 (21.6%) had a missing event during the one-year follow-up period.

Of the 65 patients with dementia who had a previous missing event at baseline, 28 had a missing event during the one-year follow-up period (recurrence rate of 43.1%). Of the 171 who did not have a previous missing event at baseline, 23 had a missing event during the one-year follow-up period (incidence rate of 13.5%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Incidence rate and recurrence rate of missing events due to wandering

Characteristics of those who had “missing” events

The factors at baseline were tested with the differences between those who did and those who did not have a missing event during the one-year follow-up period to investigate further factors related to the incidence and recurrence of missing events.

Of the 236 patients with dementia, 171 (72.5%) had Alzheimer's disease, 21 (8.9%) had dementia with Lewy bodies or Parkinson's disease with dementia, 17 (7.2%) had vascular dementia, five (2.1%) had frontotemporal dementia, and 22 (9.3%) had another form of dementia (Table 2).

In the year of follow-up, the group with no missing events, the incidence group, and the recurrence group did not differ significantly in basic attributes (e.g., sex, age, years of education, living alone or financial difficulty) or lifestyle (e.g., alcohol consumption, smoking, sleep disorder, absence of daily exercise; Table 2).

Group differences were seen in MMSE, DBD, ADAS, RCPM, and GDS scores in medical factors. The mean MMSE score was significantly lower in the recurrence group (16.5) than in the incidence group (18.2) and in the group with no missing events (19.3; p<0.01). The mean DBD score was significantly higher in the recurrence group (26.1) than in the incidence group (19.6) and in the group with no missing events (15.7; p<0.001). The mean ADAS score was significantly higher in the recurrence group (23.2) than in the incidence group (18.3) and in the group with no missing events (17.8; p<0.001). The mean RCPM score was significantly lower in the recurrence group (17.6) than in the incidence group (19.4) and in the group with no missing events (21.9; p<0.001). The GDS score differed significantly between the incidence group and the recurrence group (2.9 vs. 4.9, p<0.03; Table 2).

Among caregiver factors, the ratio of those providing care every day was significantly higher in the recurrence group (92.9%) than in the incidence group (69.6%) and in the group with no missing events (74.1%; p<0.01). The GDS score of caregivers was 5.1 in the recurrence group, 3.6 in the incidence group, and 3.2 in the group with no missing events(p<0.01). The J-ZBI score was significantly higher in the recurrence group (32.6) than in the incidence group (27.4) and in the group with no missing events (20.9; p<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2: Differences in the characteristics at the baseline (No missing event group, incidence group, recurrence group after one-year follow-up)

|

Factor |

One-year follow-up |

||||

|

none |

incidence |

recurrence |

P |

||

|

(n=185) |

(n=23) |

(n=28) |

|||

|

Diagnosis |

Alzheimer’s disease, n(%) |

134(72.4) |

12(52.2) |

25(89.3) |

NA |

|

Dementia with Lewy bodies or Parkinson’s disease, n(%) |

16(8.6) |

3(13.0) |

2(7.1) |

NA |

|

|

Vascular dementia, n(%) |

13(7.0) |

3(13.0) |

1(3.6) |

NA |

|

|

Frontotemporal dementia, n(%) |

3(1.6) |

2(8.7) |

0(0.0) |

NA |

|

|

Others, n(%) |

19(10.3) |

3(13.0) |

0(0.0) |

NA |

|

|

Basic attributes |

Sex† Female, n(%) |

114(61.6) |

13(56.5) |

12(42.9) |

n.s |

|

Age, mean (SD) |

79.8(7.0) |

78.3(7.8) |

77.8(5.5) |

n.s. |

|

|

Years of education, mean (SD) |

10.6(2.8) |

10.5(2.2) |

10.7(2.9) |

n.s. |

|

|

Living alone††, n(%) |

33(17.8) |

3(13.0) |

3(10.7) |

n.s. |

|

|

Financial difficulty††, n(%) |

13(7.1) |

2(8.7) |

3(10.7) |

n.s. |

|

|

Medical factors? |

Body mass index, mean(SD) |

22.0(3.5) |

22.4(3.3) |

20.8(2.9) |

n.s. |

|

Barthel Index, mean(SD) |

94.6(11.8) |

95.4(10.4) |

93.2(10.4) |

n.s. |

|

|

Mini-Mental State Examination, mean(SD) |

19.3(3.8) * |

18.2(4.3) |

16.5(4.2) * |

0.01 |

|

|

Dementia Behavior Disturbance Scale, mean(SD) |

15.7(9.6) * |

19.6(10.4) |

26.1(13.2) * |

p<0.001 |

|

|

Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale, mean(SD) |

17.8(5.5) * |

18.3(5.5) * |

23.2(6.3) * |

p<0.001 |

|

|

Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices, mean(SD) |

21.9(5.9) * |

19.4(7.8) |

17.6(8.6) * |

0.01 |

|

|

Frontal Assessment Battery, mean(SD) |

8.7(3.3) |

7.6(3.4) |

7.3(3.2) |

n.s. |

|

|

Geriatric syndrome, mean(SD) |

4.6(3.2) |

6.3(4.6) |

4.3(2.9) |

n.s. |

|

|

Vitality index, mean(SD) |

8.6(1.4) |

8.6(1.4) |

8.3(1.4) |

n.s. |

|

|

Geriatric Depression Scale, mean(SD) |

3.5(2.8) |

4.9(3.4) * |

2.9(2.8) * |

0.03 |

|

|

Lifestyle? |

Alcohol†, n(%) |

56(30.3) |

5(21.7) |

7(25.0) |

n.s. |

|

Smoking††, n(%) |

24(13.0) |

2(8.7) |

6(21.4) |

n.s. |

|

|

Sleeping disorder†, n(%) |

71(38.8) |

14(63.6) |

10(35.7) |

n.s. |

|

|

Absence of daily exercise†, n(%) |

76(41.1) |

14(60.9) |

14(50.0) |

n.s. |

|

|

Caregiver factors |

Sex† Female, n(%) |

130(70.3) |

17(73.9) |

22(78.6) |

n.s. |

|

Age, mean(SD) |

62.2(11.8) |

63.9(13.8) |

60.8(11.4) |

n.s. |

|

|

Years of education, mean(SD) |

12.8(2.3) |

12.3(2.8) |

12(1.8) |

n.s. |

|

|

Employed†, n(%) |

108(58.4) |

11(47.8) |

14(50.0) |

n.s. |

|

|

Providing care every day, n(%) |

137(74.1)* |

16(69.6) * |

26(92.9)* |

0.01 |

|

|

Availability of other caregivers, n(%)†† |

11(5.9) |

1(4.3) |

4(14.3) |

n.s. |

|

|

Experience of caregiving for dementia patient, n(%) |

35(18.9) |

5(21.7) |

5(17.9) |

n.s. |

|

|

Attended seminar for caregiving to dementia patient, n(%) |

33(17.8) |

7(30.4) |

1(3.6) |

n.s. |

|

|

Poor physical health, n(%) |

33(17.8) |

6(26.1) |

7(25.0) |

n.s. |

|

|

Geriatric Depression Scale, mean(SD) |

3.2(2.6) * |

3.6(3.2) |

5.1(3.5) * |

0.01 |

|

|

Zarit caregiver burden interview(Japanese Ver.), mean(SD) |

20.9(14.1) * |

27.4(16.9) |

32.6(14.2) * |

p<0.001 |

|

†χ2test ††Fisher exact test,*post hoc test. NA: Not Applicable, SD: Standard Deviation, n.s.: not significant

Risk factors of incidence missing events due to wandering with dementia

Logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the risk factors for the incidence and recurrence of missing events with incidence or recurrence of missing events during the one-year follow-up period as the dependent variable and baseline factors as independent variables (Table 3).

First, a univariate logistic analysis was performed on patients with dementia with medical and caregiver-related factors as independent variables, and all models were adjusted for sex, age, years of education, and financial difficulties. The MMSE, DBD, ADAS, RCPM, and FAB scores and caregivers' GDS and J-ZBI scores significantly affected the ratio of those who had a missing event. Next, a multivariate logistic analysis was performed with variables that were significant in the univariate logistic analysis. Multivariate logistic analysis performed with missing events during the one-year follow-up period as the dependent variable showed significant differences in the MMSE, DBD scores, and J-ZBI scores. An analysis was performed separately on the incidence group and the recurrence group. Significant differences remained only for the MMSE score in the incidence group and for the ADAS score and J-ZBI scores in the recurrence group (verified in multicollinearity tests; Table 3).

Table 3: Risk factors for the incidence and recurrence due to wandering with dementia

|

Univariate logistic analysis |

Multivariate logistic analysis |

||||

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||

|

(incidence or recurrence) |

(incidence) |

(recurrence) |

|||

|

Medical factors of patients |

Mini-Mental State Examination |

0.87(0.80- 0.95)* |

0.88 (0.78- 0.99) * |

0.88 (0.78- 0.99) * |

0.90 (0.78- 1.00) |

|

Dementia Behavior Disturbance Scale |

1.07(1.03- 1.10) * |

1.04 (1.00- 1.09) * |

1.04 (0.99- 1.08) |

1.04 (0.99- 1.10) |

|

|

Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale |

1.10(1.04- 1.17) * |

1.05 (0.97- 1.14) |

1.05 (0.97- 1.13) |

1.13 (1.02- 1.25) * |

|

|

Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices |

0.92(0.87- 0.97) * |

0.95 (0.89- 1.02) |

0.96 (0.90- 1.02) |

0.97 (0.90- 1.10) |

|

|

Frontal Assessment Battery |

0.88(0.80- 0.98) * |

1.06 (0.91- 1.22) |

1.04 (0.91- 1.21) |

1.04 (0.86- 1.25) |

|

|

Geriatric syndrome |

1.07(0.98- 1.17) |

||||

|

Vitality index |

0.88(0.71- 1.10) |

||||

|

Geriatric Depression Scale |

1.04(0.93- 1.15) |

||||

|

Anti-dementia medicine |

1.32(0.63- 2.76) |

||||

|

Care giver's factors |

Caregiver’s Geriatric Depression Scale |

1.14(1.03- 1.27) * |

1.09 (0.97- 1.22) |

1.11 (0.97- 1.27) |

1.04 (0.98- 1.35) |

|

Japanese version of the Zarit caregiver burden interview |

1.04(1.02- 1.06) * |

1.03 (1.01- 1.06) * |

1.01 (0.98- 1.04) |

1.03 (1.00- 1.06) * |

|

|

Providing care every day |

1.56(0.70- 3.46) |

||||

|

Experience of caregiving for a patient with dementia |

1.09(0.50- 2.40) |

||||

|

Attended seminar for caregiving for a patient with dementia |

0.90(0.38- 2.09) |

||||

Model 1: Dependent variable is incidence or recurrence during one year follow up; model 2: Dependent variable: incidence during one year follow up; model 3: Dependent variable: recurrence during one year follow up. 95% comfidence interals in brackets. * p<0.05, Sex, age, years of education, and financial difficulties were controlled.

4. Discussion

As a result of this study, the incidence rate was13.5%, and the recurrence rate was 43.1%. These results are within the scope of those found in previous studies on the incidence rates of missing events in community-dwelling older adults. Studies on Alzheimer's disease by Rolland et al. [17], Klein et al.[8], and McShane et al. [18] found the prevalence of wandering to be 12.6%, 17.4%, and 24.0%, respectively, cross-sectional studies. Barrett et al.[2] conducted a two-year prospective longitudinal study on adults aged 60 years or older with mild dementia and found that 45.9% of participants demonstrated wandering. In a two- and half-year follow-up study by Pai et al. on those with Alzheimer's disease, the incidence rate was 33.3%, and the recurrence rate was 40%[19].

However, the present study is the first cohort study to assess all the patients during a given period and further divide them at baseline based on whether or not they had a past missing event. We have also examined the recurrence and incidence of missing events. Thus, the present study results are considered highly reliable observational findings. The present study results suggest that people diagnosed with dementia require more careful observation to monitor the possibility of going missing and those with a missing incident require cautious attention.

Tests of the relationship between missing events during the one-year follow-up period and personal attributes, such as sex, age, years of education, living alone, or financial difficulty at baseline did not reveal any significant findings consistent with the findings of previous studies [4,20].

Although univariate logistic analysis showed that medical factors, such as MMSE, DBD, ADAS, RCPM, and FAB scores play a role, multivariate logistic analysis controlling for age, sex, years of education, and financial difficulty only showed significant effects from MMSE and DBD scores. When incidence and recurrence were examined separately, the only significant factors that remained were the MMSE score for incidence and ADAS score for recurrence. Comparing ADAS and MMSE, the former is a method for evaluating the therapeutic effect of Alzheimer’s disease, whereas the latter is a comprehensive evaluation method for cognitive function. Therefore, the recurrence of missing incidents may be more strongly influenced by the effectiveness of the treatment for dementia.

The MMSE score differed significantly between those who had a missing event during the follow-up period (mean 18.1, SD 4.8) and those who did not (mean 21.5, SD 4.4). So far, studies have found a higher likelihood of occurrence of a missing event among those with a mild or severe cognitive impairment than those with no cognitive impairment[4,7,8]. In the present study, participants with an MMSE score of 15 to 20 went missing most frequently. In particular, after one year of follow-up, the MMSE score distribution for those who had no missing events, those who had their first missing event, and those who had a recurrent missing event separately showed that those scoring ≤20 points required careful observation and those scoring ≤15 points were at a high risk of a recurrence.

Findings have also shown a higher likelihood of missing events among those with DBD[21] or a high score on the ADAS[22].

We also analyzed the relationships with variables that are considered risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia (lifestyle risk factors, such as current smoking[23], alcohol consumption[24], physical inactivity[25], and sleep disturbances[26]), but did not observe any associations between these variables and missing events. Studies have found a relationship between depression and wandering[8], but we did not find a significant association between them in the present study.

Regarding family caregivers, the univariate logistic analysis showed that a greater tendency towards wandering was observed as the family's burden increased[22]. Family caregivers of patients with a history of missing incidents had a higher sense of burden than caregivers of patients with no history of missing incidents.

Missing incidents can potentially occur with anyone whose cognitive impairment progresses, and appropriate care is required. Care by family caregivers of persons with dementia can reduce specific dementia-related behaviors and the frequency and seriousness of psychological symptoms[27]. On the other hand, family caregivers' physical and mental health is a predictive factor of dementia-related missing events[28]. Although the severity of dementia may be one of the significant risk factors responsible for missing events, the relationship between the person with dementia and their family caregivers also has a strong impact. Missing events are the most burdensome behavior for family caregivers[17] and lead many caregivers to lock the doors[18].

While effective management and technological interventions can help lessen the burden on family caregivers[29], only about 20% of the participants surveyed in our study had participated in a seminar or other event providing information on dementia. A social environment that can support family caregivers needs to be developed to reduce the sense of burden on family caregivers who are caring for persons with dementia and the number of missing events due to wandering.

A significant aspect of the present study is a prospective cohort study examining all patients who visited the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology during a certain period. It had not been done in previous studies, offering new insights.

However, we have limitations of this study. First, we did not collect clinical data as our endpoint and could not include clinical information that has a causal association with wandering in our analysis. Moreover, the follow-up period was only one year, and longer-term follow-up studies are needed.

5. Conclusion

We conducted a prospective cohort study based on symptom registration with missing events due to wandering as the endpoint. We calculated the incidence and recurrence rate of missing events during the follow-up and then analyzed which factors could more clearly predict the incidence of missing events. Of the 65 patients with dementia with a previous missing event at baseline, 28 had a missing event during the one-year follow-up period (recurrence rate of 43.1%). Of the 171 who did not have a previous missing event at baseline, 23 had a missing event during the one-year follow-up period (incidence rate of 13.5%). The result of multivariate logistic analysis, the MMSE, DBD scores, and J-ZBI scores showed significant differences between those who had missing events and the others. Prevention of missing events requires focused attention on changes in the Mini-Mental State Examination, Dementia Behavior Disturbance Scale, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale scores, and the development of a social environment for supporting family caregivers.

Acknowledgement

This research was funded by the Health Labour Sciences Research Grant (201816001B) and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (21H00792), Japan.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO. Dementia 10(2020).

- Barrett B, Bulat T, Schultz S K, et al. Factors Associated With Wandering Behaviors in Veterans With Mild Dementia: A Prospective Longitudinal Community-Based Study. American journal of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias 33(2018): 100-111.

- Algase DL, Moore DH, Vandeweerd C, et al. Mapping the maze of terms and definitions in dementia-related wandering. Aging Ment Health 11(2007): 686-698.

- Hope T, et al. Wandering in dementia: a longitudinal study. Int Psychogeriatr 13(2001): 137-147.

- Adekoya AA, & Guse L. Wandering Behavior From the Perspectives of Older Adults With Mild to Moderate Dementia in Long-Term Care. Res Gerontol Nurs 12(2019): 239-247.

- Lai CK, & Arthur DG. Wandering behaviour in people with dementia. J Adv Nurs 44(2003): 173-182.

- Lovheim H, Sandman PO, Karlsson S, et al. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in relation to level of cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr 20(2008): 777-789.

- Klein DA, et al. Wandering behaviour in community-residing persons with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 14(2017): 272-279.

- Kikuchi K, Ijuin M, Awata S, et al. Exploratory research on outcomes for individuals missing through dementia wandering in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int 19(2019): 902-906.

- Saito T, Murata C, Jeong S, et al. Prevention of accidental deaths among people with dementia missing in the community in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int 18(2018): 1301-1302.

- Jeong S, Inoue Y, Saito T, et al. The characteristics of elderly who wandered and got lost due to dementia and the municipalities' measures: All municipalities of A prefecture (54 municipalities) in 2014-2015. Journal of Japanese Society for Dementia Care 17(1987): 457-463.

- Dawson P, & Reid DW. Behavioral dimensions of patients at risk of wandering. Gerontologist 27(1987): 104-107.

- Nelson AL. Evidence-based protocols for managing wandering behaviors. Springer Publishing Company 10(2007).

- Houston AM, Brown LM, Rowe MA, et al. The informal caregivers' perception of wandering. American journal of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias 26(2011): 616-622.

- Rowe M, et al. The Concept of Missing Incidents in Persons with Dementia. Healthcare (Basel) 3(2015): 1121-1132.

- Arai Y, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Zarit Caregiver Burden interview. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 51(1997): 281-287.

- Rolland, Y. et al. [Wandering and Alzheimer's type disease. Descriptive study. REAL.FR research program on Alzheimer's disease and management]. Rev Med Interne 24 (2003): 333-338.

- McShane R, et al. Getting lost in dementia: a longitudinal study of a behavioral symptom. Int Psychogeriatr. 10(1998): 253-260.

- Pai MC, & Lee CC. The Incidence and Recurrence of Getting Lost in Community-Dwelling People with Alzheimer's Disease: A Two and a Half-Year Follow-Up. PLoS One 11(2016): e0155480.

- Ali N, et al. Risk assessment of wandering behavior in mild dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 31(2016): 367-374.

- O'Rourke N, Bedard M, & Bachner YG. Measurement and analysis of behavioural disturbance among community-dwelling and institutionalized persons with dementia. Aging Ment Health 11(2007): 256-265.

- Rolland Y, et al. Wandering behavior and Alzheimer disease. The REAL.FR prospective study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 21(2007): 31-38.

- Plassman BL, Williams JW, Jr Burke, et al. Systematic review: factors associated with risk for and possible prevention of cognitive decline in later life. Ann Intern Med 153(2010): 182-193.

- Neafsey EJ, & Collins MA. Moderate alcohol consumption and cognitive risk. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 7(2018): 465-484.

- Blondell SJ, Hammersley-Mather R, & Veerman JL. Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 14(2014): 510.

- Potvin O, et al. Sleep quality and 1-year incident cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults. Sleep 35(2012): 491-499.

- Brodaty H, & Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry 169(2012): 946-953.

- Peng M, Chiu YC, Liang J, et al. Risky wandering behaviors of persons with dementia predict family caregivers' health outcomes. Aging Ment Health 22 (2018): 1650-1657.

- Neubauer NA, et al. What do we know about technologies for dementia-related wandering? A scoping review: Examen de la portee : Que savons-nous a propos des technologies de gestion de l'errance liee a la demence? Can J Occup Ther 85(2018): 196-208