Characteristics Associated with Choosing Long-Acting Reversible Contraception in Rural Guatemala: A Secondary Analysis of a Cluster-Randomized Trial

Article Information

Margo S Harrison1*, Saskia Bunge-Montes2, Claudia Rivera2, Andrea Jimenez-Zambrano1, Gretchen Heinrichs3, Antonio Bolanos2, Edwin Asturias1, Stephen Berman1, Jeanelle Sheeder1

1University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, USA

2Fundación para la Salud Integral de los Guatemaltecos, Quetzaltenango, Guatemala

3Denver Health, Denver, USA

*Corresponding Author: Margo S Harrison, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Mail Stop B198-2, Academic Office 1, 12631 E. 17th Avenue, Rm 4211, Aurora, Colorado 80045, USA

Received: 07 June 2021; Accepted: 14 June 2021; Published: 25 June 2021

Citation:

Margo S Harrison, Saskia Bunge-Montes, Claudia Rivera, Andrea Jimenez-Zambrano, Gretchen Heinrichs, Antonio Bolanos, Edwin Asturias, Stephen Berman, Jeanelle Sheeder. Characteristics Associated with Choosing Long-Acting Reversible Contraception in Rural Guatemala: A Secondary Analysis of a Cluster-Randomized Trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology Research 4 (2021): 131-139.

Share at FacebookAbstract

Design: We conducted a secondary analysis of a cluster-randomized trial to observe characteristics associated with women who chose to use long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) compared to those who chose a short-acting method 12 months after enrollment.

Methods: The trial studied four control and four intervention clusters where the intervention clusters were offered contraception at their 40-day routine postpartum visit; control clusters received standard care, which included comprehensive postpartum contraceptive counseling. Women were followed through twelve months postpartum.

Results: The study enrolled 208 women; 94 (87.0%) were in the intervention group and 91 (91.0%) were in the control group. At twelve months, with 130 (70.3%) women using contraception at that time. 94 women (50.8%) were using a short acting method compared to 33 (17.9%) who chose a long-acting method, irrespective of cluster. In mixed effect regression modeling adjusted for cluster, characteristics associated with a reduced likelihood of choosing long-acting contraception in multivariate modeling included age (aRR 0.98 [0.96,0.99], p = 0.008) and any education (compared to no education; aRR 0.76 [0.60,0.95], p = 0.02). Women who were sexually active by their enrollment visit (40 days postpartum) were 30% more likely to opt for a long-acting method (aRR 1.30 [1.03,1.63], p = 0.03).

Conclusion: Older and more educated women were less likely to be using LARC a year after enrollment, while women with a history of early postpartum sexual activity were more likely to choose LARC.

Keywords

Postpartum Contraception, LARC, SARC, Implant, Guatemala

Postpartum Contraception articles Postpartum Contraception Research articles Postpartum Contraception review articles Postpartum Contraception PubMed articles Postpartum Contraception PubMed Central articles Postpartum Contraception 2023 articles Postpartum Contraception 2024 articles Postpartum Contraception Scopus articles Postpartum Contraception impact factor journals Postpartum Contraception Scopus journals Postpartum Contraception PubMed journals Postpartum Contraception medical journals Postpartum Contraception free journals Postpartum Contraception best journals Postpartum Contraception top journals Postpartum Contraception free medical journals Postpartum Contraception famous journals Postpartum Contraception Google Scholar indexed journals LARC articles LARC Research articles LARC review articles LARC PubMed articles LARC PubMed Central articles LARC 2023 articles LARC 2024 articles LARC Scopus articles LARC impact factor journals LARC Scopus journals LARC PubMed journals LARC medical journals LARC free journals LARC best journals LARC top journals LARC free medical journals LARC famous journals LARC Google Scholar indexed journals SARC articles SARC Research articles SARC review articles SARC PubMed articles SARC PubMed Central articles SARC 2023 articles SARC 2024 articles SARC Scopus articles SARC impact factor journals SARC Scopus journals SARC PubMed journals SARC medical journals SARC free journals SARC best journals SARC top journals SARC free medical journals SARC famous journals SARC Google Scholar indexed journals Implant articles Implant Research articles Implant review articles Implant PubMed articles Implant PubMed Central articles Implant 2023 articles Implant 2024 articles Implant Scopus articles Implant impact factor journals Implant Scopus journals Implant PubMed journals Implant medical journals Implant free journals Implant best journals Implant top journals Implant free medical journals Implant famous journals Implant Google Scholar indexed journals Guatemala articles Guatemala Research articles Guatemala review articles Guatemala PubMed articles Guatemala PubMed Central articles Guatemala 2023 articles Guatemala 2024 articles Guatemala Scopus articles Guatemala impact factor journals Guatemala Scopus journals Guatemala PubMed journals Guatemala medical journals Guatemala free journals Guatemala best journals Guatemala top journals Guatemala free medical journals Guatemala famous journals Guatemala Google Scholar indexed journals obstetrical articles obstetrical Research articles obstetrical review articles obstetrical PubMed articles obstetrical PubMed Central articles obstetrical 2023 articles obstetrical 2024 articles obstetrical Scopus articles obstetrical impact factor journals obstetrical Scopus journals obstetrical PubMed journals obstetrical medical journals obstetrical free journals obstetrical best journals obstetrical top journals obstetrical free medical journals obstetrical famous journals obstetrical Google Scholar indexed journals infant articles infant Research articles infant review articles infant PubMed articles infant PubMed Central articles infant 2023 articles infant 2024 articles infant Scopus articles infant impact factor journals infant Scopus journals infant PubMed journals infant medical journals infant free journals infant best journals infant top journals infant free medical journals infant famous journals infant Google Scholar indexed journals postpartum articles postpartum Research articles postpartum review articles postpartum PubMed articles postpartum PubMed Central articles postpartum 2023 articles postpartum 2024 articles postpartum Scopus articles postpartum impact factor journals postpartum Scopus journals postpartum PubMed journals postpartum medical journals postpartum free journals postpartum best journals postpartum top journals postpartum free medical journals postpartum famous journals postpartum Google Scholar indexed journals contraceptive articles contraceptive Research articles contraceptive review articles contraceptive PubMed articles contraceptive PubMed Central articles contraceptive 2023 articles contraceptive 2024 articles contraceptive Scopus articles contraceptive impact factor journals contraceptive Scopus journals contraceptive PubMed journals contraceptive medical journals contraceptive free journals contraceptive best journals contraceptive top journals contraceptive free medical journals contraceptive famous journals contraceptive Google Scholar indexed journals Reproductive Health articles Reproductive Health Research articles Reproductive Health review articles Reproductive Health PubMed articles Reproductive Health PubMed Central articles Reproductive Health 2023 articles Reproductive Health 2024 articles Reproductive Health Scopus articles Reproductive Health impact factor journals Reproductive Health Scopus journals Reproductive Health PubMed journals Reproductive Health medical journals Reproductive Health free journals Reproductive Health best journals Reproductive Health top journals Reproductive Health free medical journals Reproductive Health famous journals Reproductive Health Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

Abbreviations:

WHO: World Health Organization; PAHO: Pan American Health Organization; LARC: Long-acting reversible contraceptives; SARC: Short-acting reversible contraceptives

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization supports provision of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) in the postpartum setting to properly space and prevent undesired pregnancies because they have high satisfaction and continuation rates [1, 2]. The Pan-American Health Organization has advised that increased provision of LARC could achieve family planning goals for the Latin American region and should be promoted [3]. Use of postpartum LARC in Guatemala is moderate overall, but rates have historically been low in the Southwest Trifinio region [4-6]. Barriers to LARC have prevented expected utilization in this rural, agricultural community; in response to this gap in modern contraceptive provision, we implemented an intervention aimed to increased uptake of postpartum LARC by offering the implant and other contraceptives to women in their homes, free of charge, at their postpartum visits, in the setting of a cluster-randomized trial [5, 7]. We had a positive trial and found that uptake of the implant was higher in intervention than control clusters (25% vs 3%, p < 0.001) [4].

For this secondary analysis, our objective was to observe what characteristics were associated with women who chose LARC (the implant and the intrauterine device [IUD]) as compared to women who chose a shorter-acting option. Therefore, among women who were using contraception at the 12-month follow-up timepoint, we analyzed how those who chose a long-acting compared to those who chose a short-acting method (SARC). For the purposes of this analysis, LARC included the implant and the intrauterine device (although only the implant was included as part of the study intervention), and SARC included contraceptive pills, condoms, and the injection.

2. Methods

2.1 Design

This study is a secondary analysis of a prospective, non-blinded, cluster-randomized trial; the protocol has been published for further detail on the original trial [5].

2.2 Setting

In Southwest Guatemala there is region known locally as the Southwest Trifinio where the University of Colorado has a collaboration with a local agribusiness [8]. Together, the organizations established the Center for Human Development, which is a local clinic that also serves as an umbrella organization for community-based maternal and child health nursing programming [8]. The maternal program provides antepartum and postpartum care in the home setting and is called Madres Sanas [8]. The cluster-randomized trial was layered on top of this healthcare infrastructure [5].

2.3 Population

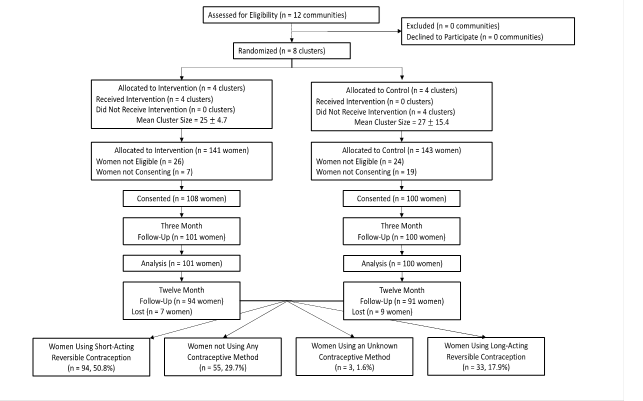

For the purposes of this secondary analysis, all women who were followed through 12 months post-enrollment without missing data on whether or not they were using contraception at that time were considered in this analysis. Women were excluded if they were not using a contraceptive method, or there was missing data on the type of contraceptive method they were currently using. The population is shown in detail in Figure 1.

2.4 Outcomes

Our intention was, among the entire population of women who were using contraception by 12 months after enrollment in the study, to determine characteristics associated with women who chose LARC as compared to those using SARC.

2.5 Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were used to generate percentages and counts of characteristics (sociodemographics, medical and obstetrical history) of the women using contraceptives overall and by type of contraceptive—LARC versus SARC. We performed comparisons of these characteristics in a mixed effects regression adjusted for cluster. All characteristics with a p-value < 0.20 were included in a multivariable model (mixed effects regression adjusted for cluster) to observe which were associated with LARC use 12 months post-enrollment. STATA software version 15.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for analysis.

3. Results

The flow diagram (Figure 1) presents the original cluster randomized trial with the populations for the current analysis listed at the bottom of the figure. By 12 months, 94 women from the intervention clusters and 91 from the control clusters were available for follow-up, which represents 88.9% of the originally enrolled cohort. 94 (50.8%) of the cohort was using SARC by 12 months, 55 (29.7%) were not using a method, 3 (1.6%) were missing data on the type of contraception used, and 33 (17.9%) were using LARC.

Table 1 describes the 127 women who were using contraception by 12 months post-enrollment in terms of their contraceptive choice. No women were using condoms, 4 (3.2%) were using the contraceptive pill, 90 (70.8%) were using the injectable contraceptive, 28 (22.0%) had an implant in situ, 1 (0.8%) had obtained an IUD, and 4 (3.2%) women in the cohort had been surgically sterilized. Table 2 describes the subpopulations of women using SARC and LARC as well as the overall cohort. The women in the study had a median age of 23 years old, with most having had some education (around 90%), and they were predominantly not single (90%). The cohort had a large primiparous subpopulation (35%) and most women had been visited at least four times in the course of their pregnancy (80%) by the Madres Sanas nurses. Almost two-thirds (60%) of participants had a vaginal birth with a skilled birth attendant, with 46% delivering in a facility setting, and almost three-fourths birthed an infant weighing 2500 grams or more. By the 72-hour postpartum visit most babies were still alive (92%) and almost half were female. By the 40-day postpartum visit, 9.5% of women had been sexually active and over one-third of women reported not desiring future fertility (36%).

Women choosing LARC as compared to those choosing SARC were younger (median around 20 years versus 24), p < 0.05. The comparison groups were otherwise similar in bivariate comparisons on education (82% with some education versus 92%), marital status (85% married versus 92%), 33% primiparous versus 35%, and received four or more Madres Sanas visits (70% versus 84%), p > 0.05. The groups had a similar prevalence of vaginal birth (52% versus 63%), delivering at the hospital (39% versus 48%), delivery by a traditional birth attendant (28% versus 34%), of having an infant 2500 grams or more (70% versus 80%), and having that infant be male (45.5% versus 41.5%), p > 0.05. Most babies in both groups were born alive (82% versus 96%) and women reporting not desiring future fertility in 30% versus 38% of the cohorts, respectively, p > 0.05. Postpartum sexual activity was borderline different between the groups with 73% of women choosing LARC being inactive and 90% of women choosing SARC being inactive, p = 0.047. The primary outcome is presented in Table 3, which compared characteristics associated with LARC utilization by 12 months post-enrollment as compared to women who were using SARC at the time of analysis. All covariates with a p-value < 0.20 were included in the regression, which included maternal age, maternal education, and sexually activity by 40 days postpartum. As women aged, they were slightly less likely to choose LARC by 12 months post-enrollment (aRR 0.98 [0.96,0.99], p = 0.008). If women had any education, they were also less likely to choose LARC than more educated women (aRR 0.76 [0.60,0.95], p = 0.02). With respect to sexual activity by 40 days postpartum, women who were sexually active by that timepoint were 30% more likely to be using LARC 12 months later (aRR 1.30 [1.03,1.63], p = 0.03).

Figure 1: Consort diagram.

|

Method |

n (%) N = 127 |

|

Pills |

4 (3.2) |

|

Injection |

90 (70.8) |

|

Implant |

28 (22.0) |

|

Intrauterine Device |

1 (0.8) |

|

Female Sterilization |

4 (3.2) |

Table 1: Final method used by women followed through 12-months with a known contraceptive method.

|

Total Population (n = 127) |

Short Acting (n = 94, 74.0%) |

Long Acting (n = 33, 26.0%) |

P-Value |

|

|

Sociodemographic Characteristics |

||||

|

Age in years (median IQR) |

23.2 [19.0,25.6] |

23.8 [19.6,26.4] |

20.4 [17.5,24.3] |

0.02 |

|

Education None Any Missing |

13 (10.2%) 113 (89.0%) 1 (0.8%) |

7 (7.5%) 86 (91.5%) 1 (1.0%) |

6 (18.2%) 27 (81.8%) 0 (0.0%) |

0.09 |

|

Married Yes No Missing |

114 (89.8%) 11 (8.7%) 2 (1.6%) |

86 (91.5%) 7 (7.5%) 1 (1.0%) |

28 (84.8%) 4 (12.2%) 1 (3.0%) |

0.50 |

|

Obstetric and Antepartum Characteristics |

||||

|

Parity 0 1 2 3 4+ |

1 (0.8%) 44 (34.6%) 35 (27.5%) 20 (15.8%) 27 (21.3%) |

0 (0.0%) 33 (35.1%) 25 (26.6%) 16 (17.0%) 20 (21.3%) |

1 (3.0%) 11 (33.3%) 10 (30.3%) 4 (12.1%) 7 (21.2%) |

0.59 |

|

Number of Madres Sanas Prenatal Visits < 4 4+ Missing |

16 (12.6%) 102 (80.3%) 9 (7.1%) |

12 (12.8%) 79 (84.0%) 3 (3.2%) |

4 (12.1%) 23 (69.7%) 6 (18.2%) |

0.92 |

|

Delivery Characteristics |

||||

|

Mode of Delivery Vaginal Birth Cesarean Birth Missing |

76 (59.8%) 43 (33.9%) 8 (6.3%) |

59 (62.8%) 32 (34.0%) 3 (3.2%) |

17 (51.5%) 11 (33.3%) 5 (15.2%) |

0.80 |

|

Location of Delivery Home, Private Clinic, or Other Facility (Hospital) Missing |

60 (47.2%) 58 (45.7%) 9 (7.1%) |

46 (48.9%) 45 (47.9%) 3 (3.2%) |

14 (42.4%) 13 (39.4%) 6 (18.2%) |

0.95 |

|

Birth Attendant Comadrona (TBA, “unskilled”) Nurse or Physician (“skilled”) Missing or “I don’t know” |

41 (32.3%) 78 (61.4%) 8 (6.3%) |

32 (34.0%) 59 (62.8%) 3 (3.2%) |

9 (27.8%) 19 (57.6%) 5 (15.2%) |

0.63 |

|

Birthweight at Delivery 2500g 2500g+ Missing |

14 (11.0%) 98 (77.2%) 15 (11.8%) |

9 (9.6%) 75 (79.8%) 10 (10.6%) |

5 (15.2%) 23 (69.7%) 5 (15.2%) |

0.36 |

|

Postpartum Characteristics |

||||

|

Sex of Infant Male Female Missing |

54 (42.5%) 63 (49.6%) 10 (7.9%) |

39 (41.5%) 50 (53.2%) 5 (5.3%) |

15 (45.5%) 13 (39.4%) 5 (15.2%) |

0.49 |

|

Infant Outcome Born Alive, died before 72-hour visit Born Alive, alive at 72-hour visit Missing |

1 (0.8%) 117 (92.1%) 9 (7.1%) |

0 (0.0%) 90 (95.7%) 4 (4.3%) |

1 (3.0%) 27 (81.8%) 5 (15.2%) |

0.14 |

|

Sexual Activity Since Birth Yes No Missing |

12 (9.5%) 109 (85.8%) 6 (4.7%) |

6 (6.4%) 85 (90.4%) 3 (3.2%) |

6 (6.2%) 24 (72.7%) 3 (9.1%) |

0.047 |

|

Desired Timeframe Until Next Pregnancy Approximately 2 years Approximately 3 years > 3 years I don’t know No more children desired Missing |

1 (0.8%) 4 (3.2%) 44 (34.6%) 27 (21.3%) 46 (36.2%) 5 (3.9%) |

1 (1.0%) 4 (4.3%) 30 (31.9%) 20 (21.3%) 36 (38.3%) 3 (3.2%) |

0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 14 (42.4%) 7 (21.2%) 10 (30.3%) 2 (6.1%) |

0.98 |

Note: p-values represent a linear model adjusted for cluster

Table 2: Bivariate comparisons of women using short-acting verses long-acting reversible contraceptives.

|

Characteristic |

aRR |

CI |

P-Value |

|

Age (continuous) |

0.98 |

0.96,0.99 |

0.008 |

|

Any Education (reference: No Education) |

0.76 |

0.60,0.95 |

0.02 |

|

Sexual Activity by 40 Days Postpartum (reference: No Sexual Activity) |

1.30 |

1.03,1.63 |

0.03 |

All characteristics with p < 0.01 in bivariate comparisons included in multivariable model (linear model adjusted for cluster); this included: maternal age, maternal education, and sexual activity before 40 days postpartum

Table 3: Multivariable Model of Characteristics Associated with Use of a Long-Acting Postpartum Contraceptive Method as Compared to a Short Acting Method.

4. Discussion

Our cluster-randomized parallel-arm pragmatic trial designed to test the hypothesis that reducing barriers to accessing contraception would increase implant usage at 3 months, was a successful trial. This analysis shows that by 12 months, 70.3% of the population was using contraception, and 22.3% of that usage was attributable to LARC devices. The only characteristic associated with an increase use of LARC at that timepoint was having been sexually active in the early postpartum period, with older age and having some level of education reducing that likelihood. Regarding the finding of increasing age associated with a slightly reduced likelihood of using LARC, we believe this finding is due to a very high utilization of female sterilization as a means of contraception in this community [4]. Eligibility criteria excluded women over age 35 and those who were already using a contraceptive method [5]. Less than 10 women were excluded for age and almost 50 were excluded because they had already been sterilized. We believe given the historically high rates of sterilization as a means of controlling undesired fertility in this community and the high rates of women who had to be excluded for already having been sterilized, it is likely that this very common method of contraception accounts for the reduced likelihood of opting for LARC as women age [5]. We hypothesize that instead of choosing LARC, women are choosing sterilization, and in fact in one of our other analyses, we found that the only women switching away from the implant did so in favor of tubal ligation (data under review). We know that sterilization is one of the more common methods of contraception in Latin America and globally in low-resource settings [3, 9].

Our finding regarding education is slightly less clear to us and might benefit from more categorizations to further delineate the findings. We can only surmise that this finding is consistent with our conjecture about our age finding; we propose that more educated women may choose the most definitive method of controlling fertility (sterilization) over a reversible contraceptive device. Education has been shown to be associated with a greater likelihood of modern contraceptive use, but our finding regarding education and reduced LARC utilization should be confirmed, as prior research has suggested that increased education is associated with increased LARC uptake [10, 11]. We were pleased to note the finding that women who have already had intercourse by 40 days postpartum were 30% more likely to choose LARC. We could consider conducting an analysis of our population, generally, to determine what is associated with early sexual activity and ensure the implant is available for that population as we know those women are likely to opt for it, in an effort to prevent short interval pregnancy. This would be an interesting and easy area for quality improvement work through the Madres Sanas program. We believe that our trial was very successful as having 70% of women using contraception 12 months postpartum is high, as is the rate of LARC utilization at over one in five women [7]. Our trial, because it was pragmatic, may have resulted in varied counseling by nurse team regarding contraceptives, which may have in turn been associated with variable use in the postpartum setting that could affect the results we have presented. Additionally, this was a secondary analysis and as such the data was not designed to answer this question, specifically. Our sample size, however, is relatively large as we had good follow-up rates, and the primary study question was related to postpartum contraceptive use, so there are strengths to the results, as well.

In conclusion, in this analysis we found that there was high use of LARC 12 months postpartum in the overall cohort and high use of the these effective methods in women participating in early postpartum sexual activity, which might be considered a high-risk group for short-interval pregnancy. We intend to build on this work by exploring how we can ensure LARC is available to this subset of the population through a quality improvement project.

Funding:

Funding for this project comes from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development Women’s Reproductive Health Research K12 award (5K12HD001271-18) and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

References

- Organization WH. WHO technical consultation on postpartum and postnatal care. Geneva: World Health Organization (2010).

- Organization WH. Report of a WHO technical consultation on birth spacing: Geneva, Switzerland 13-15 June 2005. World Health Organization (2007).

- Ponce De Leon RG, Ewerling F, Serruya SJ, et al. Contraceptive use in Latin America and the Caribbean with a focus on long-acting reversible contraceptives: prevalence and inequalities in 23 countries. The Lancet Global Health 7 (2019): e227-e235.

- Harrison MS, Bunge-Montes S, Rivera C, et al. Primary and secondary three-month outcomes of a cluster-randomized trial of home-based postpartum contraceptive delivery in southwest Trifinio, Guatemala. Reprod Health 17 (2020): 127.

- Harrison MS, Bunge-Montes S, Rivera C, et al. Delivery of home-based postpartum contraception in rural Guatemalan women: a cluster-randomized trial protocol. Trials 20 (2019): 639.

- Pasha O, Goudar SS, Patel A, et al. Postpartum contraceptive use and unmet need for family planning in five low-income countries. Reprod Health 12 (2015): S11.

- Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, et al. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 203 (2010): 115.e111-115.e117.

- Asturias EJ, Heinrichs G, Domek G, et al. The Center for Human Development in Guatemala. Advances in Pediatrics 63 (2016): 357-387.

- Moore Z, Pfitzer A, Gubin R, et al. Missed opportunities for family planning: an analysis of pregnancy risk and contraceptive method use among postpartum women in 21 low- and middle-income countries. Contraception 92 (2015): 31-39.

- Rios-Zertuche D, Blanco LC, Zúñiga-Brenes P, et al. Contraceptive knowledge and use among women living in the poorest areas of five Mesoamerican countries. Contraception 95 (2017): 549-557.

- Bahamondes L, Villarroel C, Frías Guzmán N, et al. The use of long-acting reversible contraceptives in Latin America and the Caribbean: current landscape and recommendations. Human Reproduction Open 2018 (2018).