Characteristics and Outcomes Associated with Cesarean Birth as Compared to Vaginal Birth at Mizan-Tepi University Teaching Hospital, Ethiopia

Article Information

Margo S Harrison1*, Ephrem Kirub2, Tewodros Liyew2, Biruk Teshome2, Andrea Jimenez-Zambrano1, Margaret Muldrow3, Teklemariam Yarinbab2

1University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA

2Mizan-Tepi University, Department of Public Health, Mizan-Aman, Ethiopia

3Village Health Partnership, Denver, Colorado, USA

*Corresponding author: Margo S Harrison, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Mail Stop B198-2, Academic Office 1, 12631 E. 17th Avenue, Rm 4211, Aurora, Colorado 80045, USA

Received: 29 March 2021; Accepted: 07 April 2021; Published: 14 April 2021

Citation:

Margo S Harrison, Ephrem Kirub, Tewodros Liyew, Biruk Teshome, Andrea Jimenez-Zambrano, Margaret Muldrow, Teklemariam Yarinbab. Characteristics and Outcomes Associated with Cesarean Birth as Compared to Vaginal Birth at Mizan-Tepi University Teaching Hospital, Ethiopia. Journal of Women’s Health and Development 4 (2021): 047-063.

Share at FacebookAbstract

Introduction: The objective of this study was to observe characteristics and outcomes associated with cesarean birth as compared to vaginal birth.

Methods: This study was a prospective hospital-based cross-sectional analysis of a convenience sample of 1, 000 women. Data was collected on admission, delivery, and discharge by trained physician data collectors on paper forms through chart review and patient interview.

Results: Data on mode of delivery was available for 993/1000 women (0.7% missing data), 23.4% of whom underwent cesarean. These women were less likely to have labored (84.5% versus 87.4%), more likely to have been transferred (62.0% versus 45.2%), more likely to have been admitted in early labor (53.0% versus 48.6%), more likely to be in labor for longer than 24 hours (10.7% versus 3.3%) and were less likely to have multiple gestation (7.7% versus 3.9%), p < 0.05. In a Poisson model, history of cesarean (aRR 2.0, p < 0.001), transfer during labor (RR 1.5, p = 0.003), labor longer than 24 hours and larger birthweight (RR 2.7, p 0.001) were associated with an increased risk of cesarean.

Conclusion: Our analysis suggests cesarean birth is being used among women with a history of prior cesarean and in cases of labor complications (prolonged labor or transfer), but fresh stillbirth is still common in this setting.

Keywords

Mode of Delivery, Cesarean Birth, Pregnancy Outcomes, Mizan-Aman, Ethiopia

Mode of Delivery articles Mode of Delivery Research articles Mode of Delivery review articles Mode of Delivery PubMed articles Mode of Delivery PubMed Central articles Mode of Delivery 2023 articles Mode of Delivery 2024 articles Mode of Delivery Scopus articles Mode of Delivery impact factor journals Mode of Delivery Scopus journals Mode of Delivery PubMed journals Mode of Delivery medical journals Mode of Delivery free journals Mode of Delivery best journals Mode of Delivery top journals Mode of Delivery free medical journals Mode of Delivery famous journals Mode of Delivery Google Scholar indexed journals Cesarean Birth articles Cesarean Birth Research articles Cesarean Birth review articles Cesarean Birth PubMed articles Cesarean Birth PubMed Central articles Cesarean Birth 2023 articles Cesarean Birth 2024 articles Cesarean Birth Scopus articles Cesarean Birth impact factor journals Cesarean Birth Scopus journals Cesarean Birth PubMed journals Cesarean Birth medical journals Cesarean Birth free journals Cesarean Birth best journals Cesarean Birth top journals Cesarean Birth free medical journals Cesarean Birth famous journals Cesarean Birth Google Scholar indexed journals Pregnancy Outcomes articles Pregnancy Outcomes Research articles Pregnancy Outcomes review articles Pregnancy Outcomes PubMed articles Pregnancy Outcomes PubMed Central articles Pregnancy Outcomes 2023 articles Pregnancy Outcomes 2024 articles Pregnancy Outcomes Scopus articles Pregnancy Outcomes impact factor journals Pregnancy Outcomes Scopus journals Pregnancy Outcomes PubMed journals Pregnancy Outcomes medical journals Pregnancy Outcomes free journals Pregnancy Outcomes best journals Pregnancy Outcomes top journals Pregnancy Outcomes free medical journals Pregnancy Outcomes famous journals Pregnancy Outcomes Google Scholar indexed journals Mizan-Aman articles Mizan-Aman Research articles Mizan-Aman review articles Mizan-Aman PubMed articles Mizan-Aman PubMed Central articles Mizan-Aman 2023 articles Mizan-Aman 2024 articles Mizan-Aman Scopus articles Mizan-Aman impact factor journals Mizan-Aman Scopus journals Mizan-Aman PubMed journals Mizan-Aman medical journals Mizan-Aman free journals Mizan-Aman best journals Mizan-Aman top journals Mizan-Aman free medical journals Mizan-Aman famous journals Mizan-Aman Google Scholar indexed journals vaginalá articles vaginalá Research articles vaginalá review articles vaginalá PubMed articles vaginalá PubMed Central articles vaginalá 2023 articles vaginalá 2024 articles vaginalá Scopus articles vaginalá impact factor journals vaginalá Scopus journals vaginalá PubMed journals vaginalá medical journals vaginalá free journals vaginalá best journals vaginalá top journals vaginalá free medical journals vaginalá famous journals vaginalá Google Scholar indexed journals abdominal surgery articles abdominal surgery Research articles abdominal surgery review articles abdominal surgery PubMed articles abdominal surgery PubMed Central articles abdominal surgery 2023 articles abdominal surgery 2024 articles abdominal surgery Scopus articles abdominal surgery impact factor journals abdominal surgery Scopus journals abdominal surgery PubMed journals abdominal surgery medical journals abdominal surgery free journals abdominal surgery best journals abdominal surgery top journals abdominal surgery free medical journals abdominal surgery famous journals abdominal surgery Google Scholar indexed journals De-identified articles De-identified Research articles De-identified review articles De-identified PubMed articles De-identified PubMed Central articles De-identified 2023 articles De-identified 2024 articles De-identified Scopus articles De-identified impact factor journals De-identified Scopus journals De-identified PubMed journals De-identified medical journals De-identified free journals De-identified best journals De-identified top journals De-identified free medical journals De-identified famous journals De-identified Google Scholar indexed journals Sociodemographic articles Sociodemographic Research articles Sociodemographic review articles Sociodemographic PubMed articles Sociodemographic PubMed Central articles Sociodemographic 2023 articles Sociodemographic 2024 articles Sociodemographic Scopus articles Sociodemographic impact factor journals Sociodemographic Scopus journals Sociodemographic PubMed journals Sociodemographic medical journals Sociodemographic free journals Sociodemographic best journals Sociodemographic top journals Sociodemographic free medical journals Sociodemographic famous journals Sociodemographic Google Scholar indexed journals Stillbirth articles Stillbirth Research articles Stillbirth review articles Stillbirth PubMed articles Stillbirth PubMed Central articles Stillbirth 2023 articles Stillbirth 2024 articles Stillbirth Scopus articles Stillbirth impact factor journals Stillbirth Scopus journals Stillbirth PubMed journals Stillbirth medical journals Stillbirth free journals Stillbirth best journals Stillbirth top journals Stillbirth free medical journals Stillbirth famous journals Stillbirth Google Scholar indexed journals "Intranasal Oxygen articles Intranasal Oxygen Research articles Intranasal Oxygen review articles Intranasal Oxygen PubMed articles Intranasal Oxygen PubMed Central articles Intranasal Oxygen 2023 articles Intranasal Oxygen 2024 articles Intranasal Oxygen Scopus articles Intranasal Oxygen impact factor journals Intranasal Oxygen Scopus journals Intranasal Oxygen PubMed journals Intranasal Oxygen medical journals Intranasal Oxygen free journals Intranasal Oxygen best journals Intranasal Oxygen top journals Intranasal Oxygen free medical journals Intranasal Oxygen famous journals Intranasal Oxygen Google Scholar indexed journals "

Article Details

1. Introduction

Understanding and optimizing the use of cesarean birth is a global health priority and of great interest to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1, 2]. Globally, cesarean birth rates are increasing, although they remain below the recommended 10% rate in many sub-Saharan African settings [3, 4]. However, in many sub-Saharan African countries (and in other low- and middle-income countries) significant disparities in the use of cesarean birth exist [5, 6]. In many rural areas it is under-accessed and underused while in urban areas among certain populations it may be over-accessed and overused [5, 6]. Though cesarean birth can be essential to saving lives, it is also a major abdominal surgery with added risks above baseline pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality; as such, its use should be limited to medically indicated situations where optimization leads to a balance of risks and benefits [2, 5]. We wanted to observe the use of cesarean birth as compared to vaginal birth in a convenience sample of women delivering at a tertiary care facility in Mizan Aman, Mizan-Tepi University Teaching Hospital (MTUTH), in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region of Ethiopia (SNNPR). The objective of this analysis was to document mode of delivery at the hospital and characteristics and maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with cesarean birth. This was not hypothesis-driven research intended to fill a generalizable gap in knowledge, but rather an initial analysis intended to provide preliminary descriptive data that we can then use to study cesarean birth in more detail, prospectively.

Nonetheless, we did expect that the cesarean birth rate would be higher than that of the overall SNNPR region as MTUTH is a referral facility and that women with complications of pregnancy would give birth by cesarean. We also expected to observe that, similar to use of cesarean birth in other sub-Saharan African cohorts, cesarean may result in adverse pregnancy outcomes in women who necessitate the service [7, 8].

2. Methodology

2.1 Study design/setting

We conducted a prospective, hospital-based cross-sectional study at Mizan-Tepi University Teaching Hospital (MTUTH), which is located in Mizan-Aman in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region (SNNPR), Ethiopia.

2.2 Participants

The population for this study was a convenience sample of all pregnant women who consecutively delivered on labor and delivery at MTUTH between May 6 and October 21, 2019, which was the point at which 1, 000 women were included in the dataset. Only mothers who delivered after 28 completed weeks of pregnancy were included. Women were offered enrollment at admission and consented for de-identified collection of data regarding their delivery experience. Those who did not consent to have their data collected were not followed, accordingly.

2.3 Variables

We modeled our data collection documents after those

used in the Global Survey for Maternal and Perinatal Health conducted by the World Health Organization, and those of the Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research. Admission data included sociodemographic and early labor details, delivery data included details on the labor course and delivery mode, and the discharge form collected data on the postpartum course including maternal and perinatal complications and interventions. The forms used for data collection have been provided in an appendix. Common definitions for variables were defined by study authors prior to data collected, and a clear definition was included with the codebook.

2.4 Data sources/measurement

De-identified data was collected by highly trained physician data collectors with the intent of planning future quality improvement and research interventions. A combination of chart review and structured interview was used to collect information upon admission, delivery, and discharge. Data was collected on paper forms and the data collectors reviewed each other’s forms for completeness prior to data entry into REDCap for transmission and secure storage on a password protected server at the University of Colorado, Aurora, Colorado, USA [9]. Data from the paper forms were entered into REDCap 9.1.9, and STATA software version 15.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for analysis. This two-part data collection technique was used per preference of the data collectors who did not want to use personal cellular data to enter information.

2.5 Bias

We deliberately chose a cross-sectional, convenience, consecutive sample of patients for a baseline assessment of patients and their experience at MTUTH, which would have been biased by the sample that women who desired to deliver in a facility or were transferred there. No efforts were made to address any potential source of bias, but we did compare our population to the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Surveys in another analysis (under review) to describe how our sample may have differed.

2.6 Study size

MTUTH is a high-volume hospital that allowed for a large sample to be obtained over a relatively short amount of time. As a research team we agreed that collecting data on 1000 consecutive women over a number months women would hopefully give a less biased sample than a smaller sample collected over a shorter timeframe, but no formal sample size calculation was performed.

2.7 Statistical methods

As our objective was to observe characteristics and outcomes associated with cesarean birth compared to vaginal birth at MTUTH, we compared these two groups, specifically. Bivariate comparisons of sociodemographic, obstetric, labor, delivery, and pregnancy outcomes of women experiencing vaginal versus cesarean birth were performed, utilizing Fisher’s exact, Chi-squared, and Mann-Whitney U tests depending on the variables. For small cell size categorical variables the Fisher’s exact test was used, for categorical variables with larger counts and percentages, the chi-squared test was used, and more continuous variables the Mann-Whitney U test was employed. All covariates significant to p < 0.05 in bivariate comparisons were included in a multivariable Poisson model with robust error variance (because cesarean birth was prevalent) to determine which covariates were independently associated with cesarean birth. Subsequently, individual poisson regressions of maternal and perinatal outcomes (significant in the bivariate comparisons) were run with the outcomes as the dependent variable and cesarean birth as the independent variable, adjusted for all covariates significant in the original multivariable Poisson model, to describe the association between cesarean birth and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

2.8 Ethics

This quality improvement survey was given an exempt from human subjects’ research approval (COMIRB # 18-2738) by the University of Colorado and approval. Despite the quality improvement nature of the work and the fact that only de-identified data was collected, oral consent was obtained from each woman before any of her data was recorded.

3. Results

3.1 Participants

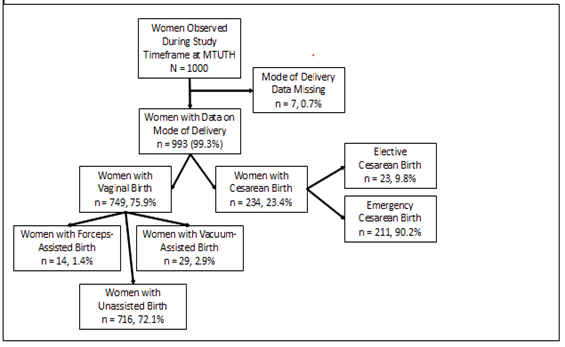

As shown in Figure 1, 1, 000 women on whom data was collected, 993 (99.3% of the study population) included information on mode of delivery (how the woman gave birth).

Figure 1: Study Population by Mode of Delivery (Cesarean versus Vaginal Birth).

3.2 Descriptive data

Almost a quarter (23.4%, n = 234) of women delivered by way of cesarean, with the remainder experiencing vaginal birth. The majority of women (90.2%) underwent cesarean birth in an emergent setting with the remaining (9.8%) of cesareans classified as elective. In terms of characteristics of the populations (Table 1), the median age of women delivering by cesarean was 25 (interquartile range [IQR] 21, 28), was almost statistically different than women delivering vaginally (p = 0.06). Compared to women who experienced vaginal birth, those that gave birth by cesarean were no different in education level, religion, relationship status, months since last delivery, gestational age, HIV status, or number of prenatal visits, p > 0.05. However, the proportion of cesarean birth was higher among women living in urban areas (65.0% versus 51.3%) and among women with a history of cesarean birth (14.1% versus 2.1%), p < 0.001. Outcome Data, Characteristics Associated with Cesarean Birth in Bivariate Comparisons (Table 2): Women who underwent cesarean birth compared to vaginal had a very different labor experience. Those experiencing cesarean birth were more likely to have been augmented (12.3% versus 12.1%) and less likely to be in spontaneous labor (84.5% versus 87.4%), more likely to have been transferred during labor (62.0% versus 45.2%), to be in latent versus active labor on admission as determined by cervical dilation (median of 3cm versus median of 4cm), to have a longer duration of labor (10.7% experience labor > 24 hours compared to 3.3%), and not have had their partograph completely utilized (30.8% versus 71.7%), p < 0.05. They also had less vaginal exams (median 2 exams versus 3 exams), experienced more antepartum hemorrhage (4.3% versus 1.6%), had larger babies (median 3200 grams versus 3000 grams), and were less likely to be carrying multiple gestations (7.7% not multiple gestation versus 3.9%), p < 0.05. Anesthesia use and delivery provider varied by vaginal versus cesarean birth, as expected.

Outcome Data, Outcomes Associated with Cesarean Birth in Bivariate Comparisons (Table 3): Complications of delivery also varied by mode of birth. Postpartum blood transfusion (4.7% versus 0.5%), antibiotic administration (30.3% versus 2.2%), and hypertensive treatment (2.6% versus 2.4%) were more common after cesarean birth, p < 0.05. Infants born to mothers by cesarean had a lower median 5-minute apgar score (8 versus 9) and were more likely to have a fresh stillbirth (6.0% versus 2.0%), p < 0.05. However, macerated stillbirths were more likely to be delivered vaginally (1.5% vaginally versus 0.4% by cesarean). Both maternal and neonatal length of hospitalization statistically significantly varied by mode of delivery, as

expected. Outcome Data, Characteristics Associated with Cesarean Birth in Multivariable Model (Table 4A): Our final table illustrates the findings of both our Poisson model of characteristics associated with experiencing cesarean birth (4A) followed by independently run Poisson regressions where cesarean birth was the dependent variable testing its adjusted association with various maternal and perinatal outcomes (4B). All statistically significant variables with p < 0.05 in Tables 1 & 2 were included in the Poisson model with the addition of often important covariates age and parity, as both had borderline significance of p = 0.06. Only statistically significant associations are shared in Table 2A; characteristics associated with an increased risk of cesarean birth include: history of cesarean birth (aRR 2.0), having been transferred in labor (aRR 1.5), being in labor between 12 and 24 hours (aRR 1.3; compared to less than 12 hours) or being in labor longer than 24 hours (aRR 2.7; also compared to less than 12 hours), and carrying a fetus with a birthweight of 2500 grams (aRR 2.7; as compared to a baby with a birthweight < 2500 grams), although this last covariate is unknown until after birth, p < 0.05. Regarding characteristics that were independently associated with a reduced risk of cesarean birth, with each increasing centimeter of dilation of the cervix on admission to the hospital, there was an associated aRR of 0.9, and partograph completion had an aRR 0.6, p < 0.05 for both variables. Outcome Data, Outcomes Associated with Cesarean Birth in Individual, Adjusted Multivariable Models (Table 4B): Independent Poisson regressions of outcomes noted to be statistically significant in bivariate comparisons (Table 3) were run with cesarean birth as the dependent variable, adjusted for the statistically significant covariates (reported in Table 4A). Maternal interventions tested included postpartum blood transfusion, antibiotics, and hypertensive or anticonvulsant therapy. Cesarean birth was only associated with increased adjusted odds of antibiotic administration (aRR 10.5, p < 0.001), which could have been due to prophylactic administration [10]. The neonatal outcomes we tested were Apgar score, odds of live birth, and odds of the neonate being alive on discharge from the hospital; cesarean birth was associa-ted with a reduced risk of having an Apgar score of greater than 7 at five minutes (aRR 0.9, p < 0.001).

|

Characteristic |

Overall Population |

Bivariate Comparisons |

||

|

N (%) N = 993 |

Vaginal Birth (n = 759, 75.9%) |

Cesarean Birth (n = 234, 23.4%) |

P-Value |

|

|

Age in years, Median (IQR) |

24 [20, 28] |

24 [20, 28] |

25 [21, 28] |

0.06a |

|

Missing |

1 (0.1%) |

* |

* |

|

|

Education |

0.60b |

|||

|

Unable to read & write |

232 (23.4%) |

173 (22.8%) |

59 (25.2%) |

|

|

Read & write only |

54 (5.4%) |

46 (6.0%) |

8 (3.4%) |

|

|

Primary school |

396 (39.9%) |

302 (39.8%) |

94 (40.2%) |

|

|

Secondary school |

138 (13.9%) |

106 (14.0%) |

32 (13.7%) |

|

|

Higher education |

172 (17.3%) |

131 (17.3%) |

41 (17.5%) |

|

|

Missing |

1 (0.1%) |

1 (0.1%) |

(0.0%) |

|

|

Religion |

0.47c |

|||

|

Muslim |

110 (11.1%) |

79 (10.4%) |

31 (13.3%) |

|

|

Orthodox Christian or Jehovah’s Witness |

337 (33.9%) |

258 (34.0%) |

79 (33.8%) |

|

|

Protestant |

545 (54.9%) |

421 (55.5%) |

124 (53.0%) |

|

|

Missing |

1 (0.1%) |

1 (0.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

|

Relationship Status |

0.48b |

|||

|

Single |

26 (2.6%) |

22 (2.9%) |

4 (1.7%) |

|

|

Not single |

959 (96.6%) |

730 (96.2%) |

229 (97.9%) |

|

|

Missing |

8 (0.8%) |

7 (0.9%) |

1 (0.4%) |

|

|

Woreda |

<0.001c |

|||

|

Urban |

541 (54.5%) |

389 (51.3%) |

152 (65.0%) |

|

|

Rural |

452 (45.5%) |

370 (48.7%) |

82 (35.0%) |

|

|

Parity |

0.06c |

|||

|

0 |

428 (42.8%) |

325 (42.8%) |

101 (43.3%) |

|

|

1 |

263 (26.3%) |

199 (26.2%) |

63 (26.9%) |

|

|

2 |

144 (14.4%) |

120 (15.8%) |

23 (9.8%) |

|

|

3 |

68 (6.8%) |

50 (6.7%) |

17 (7.3%) |

|

|

4 |

37 (3.7%) |

29 (3.8%) |

8 (3.4%) |

|

|

5+ |

58 (5.8%) |

35 (4.6%) |

22 (9.4%) |

|

|

Missing |

2 (0.2%) |

1 (0.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

|

Months Since Last Delivery (parity 1+ n = 572) |

0.53c 0.46a |

|||

|

< 24 months |

46 (4.6%) |

37 (4.9%) |

9 (3.9%) |

|

|

24+ months |

521 (52.5%) |

398 (52.4%) |

123 (52.6%) |

|

|

Missing |

429 (42.9%) |

324 (42.7%) |

102 (43.6%) |

|

|

Median (IQR) |

56 [36, 84] |

60 [36, 84] |

48 [36, 84] |

|

|

Gestational Age Determination |

0.32c |

|||

|

Clinical Exam (Fundal Height) |

472 (47.4%) |

367 (48.6%) |

102 (43.6%) |

|

|

Last Menstrual Period |

66 (6.6%) |

47 (6.2%) |

19 (8.1%) |

|

|

Ultrasound |

457 (45.9%) |

341 (45.2%) |

113 (48.3%) |

|

|

Missing |

5 (0.5%) |

4 (0.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

|

History of Cesarean Birth |

<0.001b |

|||

|

0 |

942 (94.9%) |

741 (97.6%) |

201 (85.9%) |

|

|

1 |

44 (4.4%) |

15(2.0%) |

29 (12.4%) |

|

|

2+ |

5 (0.5%) |

1 (0.1%) |

4 (1.7%) |

|

|

Missing |

2 (0.2%) |

2 (0.3%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

|

HIV+ |

0.34b |

|||

|

Yes |

21 (2.1%) |

19 (2.5%) |

2 (0.9%) |

|

|

No |

964 (97.1%) |

734 (96.7%) |

230 (98.3%) |

|

|

Missing |

8 (0.8%) |

6 (0.8%) |

2 (0.9%) |

|

|

Number of Prenatal Visits |

0.38c |

|||

|

0 |

19 (1.9%) |

11 (1.5%) |

8 (3.4%) |

|

|

< 8 |

914 (92.0%) |

703 (92.6%) |

211 (90.2%) |

|

|

8+ |

55 (5.5%) |

40 (5.3%) |

15 (6.4%) |

|

|

Missing |

5 (0.5%) |

5 (0.7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

a: Mann Whitney U test

b: Fisher’s Exact test

c: Chi-squared test

*unknown mode of delivery for missing data

Note: missing data was not included in bivariate comparisons and chi-squared testing was used for cell sizes above 5

Table 1: Sociodemographic and Obstetric Characteristics of Women Overall and by Mode of Delivery.

|

Characteristic |

Overall Population |

Bivariate Comparisons |

|||

|

N (%) N = 993 |

Vaginal Birth (n = 759, 75.9%) |

Cesarean Birth (n = 234, 23.4%) |

P-Value |

||

|

Onset of Labor |

<0.001a |

||||

|

Spontaneous |

841 (84.7%) |

663 (87.4%) |

178 (84.5%) |

||

|

Augmented/Induced |

123 (12.4%) |

92 (12.1%) |

31 (12.3%) |

||

|

Not Applicable (not in labor) |

28 (2.8%) |

3 (0.4%) |

25 (2.8%) |

||

|

Missing |

1 (0.1%) |

1 (0.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

||

|

Transferred During Labor |

<0.001b |

||||

|

No |

505 (50.9%) |

416 (54.8%) |

89 (38.0%) |

||

|

Yes |

488 (49.1%) |

343 (45.2%) |

145 (62.0%) |

||

|

If Transferred, Transferring Facility (Transferred n = 481) |

1.0a |

||||

|

Health Center |

471 (96.8%) |

331 (97.9%) |

140(97.9%) |

||

|

Private Clinic |

7 (1.4%) |

5 (1.5%) |

2 (1.4%) |

||

|

Primary Hospital |

3 (0.6%) |

2 (0.6%) |

1 (0.7%) |

||

|

Cervical Exam on Admission |

<0.001b |

||||

|

<4 cm (latent labor) |

493 (49.7%) |

369 (48.6%) |

124 (53.0%) |

||

|

4+ cm (active labor) |

469 (47.2%) |

376 (49.5%) |

93 (39.7%) |

||

|

Missing or “Not done” or “Not Applicable” |

31 (3.1%) |

14 (1.8%) |

17 (7.3%) |

||

|

Fetal Heart Rate Auscultated at Admission |

0.26a |

||||

|

Yes |

943 (95.0%) |

724 (95.4%) |

219 (93.6%) |

||

|

No (Fetal Demise) |

39 (3.9%) |

29 (3.8%) |

10 (4.3%) |

||

|

Not Auscultated |

2 (0.2%) |

1 (0.1%) |

1 (0.4%) |

||

|

Missing |

9 (0.9%) |

5 (0.7%) |

4 (1.7%) |

||

|

Duration of Labor |

<0.001b |

||||

|

Not Applicable (not in labor) |

33 (3.3%) |

6 (0.8%) |

27 (11.5%) |

||

|

< 12 hours |

510 (51.2%) |

424 (55.9%) |

86 (36.8%) |

||

|

12 – 24 hours |

400 (40.2%) |

304 (40.1%) |

96 (41.0%) |

||

|

24+ hours |

50 (5.2%) |

25 (3.3%) |

25 (10.7%) |

||

|

Partograph Used |

<0.001a |

||||

|

Not Applicable (not in labor) |

271 (27.3%) |

133 (17.5%) |

138 (56.0%) |

||

|

No |

94 (9.5%) |

74 (9.8%) |

20 (8.6%) |

||

|

Yes, Incomplete |

10 (1.0%) |

6 (0.8%) |

4 (1.7%) |

||

|

Yes, Complete |

616 (62.0%) |

544 (71.7%) |

72 (30.8%) |

||

|

Missing |

2 (0.2%) |

2 (0.3%) |

0 (0.0%) |

||

|

Number of Vaginal Exams Median (IQR) |

3 [2, 3] |

3 [2, 4] |

2 [1, 3] |

<0.001c |

|

|

Missing |

5 (0.5%) |

1 (0.1%) |

4 (1.7%) |

||

|

Antepartum Hemorrhage |

0.04b |

||||

|

No |

970 (97.7%) |

746 (98.3%) |

224 (95.7%) |

||

|

Yes |

22 (2.2%) |

12 (1.6%) |

10 (4.3%) |

||

|

Missing |

1 (0.1%) |

1 (0.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

||

|

Chorioamnionitis |

0.63a |

||||

|

No |

987 (0.6%) |

755 (99.5%) |

987 (99.2%) |

||

|

Yes |

6 (99.3%) |

4 (0.5%) |

6 (0.9%) |

||

|

Antepartum Pre-eclampsia/Eclampsia/Chronic Hypertension |

0.68b |

||||

|

No |

945 (95.2%) |

724 (95.4%) |

221 (94.4%) |

||

|

Yes |

47 (4.7%) |

34 (4.5%) |

13 (5.6%) |

||

|

Missing |

1 (0.1%) |

1 (0.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

||

|

Anesthesia for Birth |

<0.001a |

||||

|

None |

672 (67.7%) |

671 (88.4%) |

1 (0.4%) |

||

|

Any |

321 (32.4%) |

88 (11.6%) |

233 (99.6%) |

||

|

Provider who Delivered the Infant |

<0.001a |

||||

|

Midwife |

730 (73.2%) |

729 (96.1%) |

1 (0.4%) |

||

|

General Practitioner |

10 (1.0%) |

9 (1.2%) |

1 (0.4%) |

||

|

Integrated Emergency and Surgical Officer |

242 (24.3%) |

20 (2.6%) |

222 (95.3%) |

||

|

Ob/Gyn Resident or Attending |

10 (1.0%) |

1 (0.1%) |

9 (3.9%) |

||

|

Missing |

1 (0.1%) |

* |

* |

||

|

Gestational Age at Delivery |

0.29b |

||||

|

Preterm (< 37 weeks) |

103 (10.4%) |

85 (11.2%) |

18 (7.7%) |

||

|

Term ( 37 weeks) |

887 (89.2%) |

672 (88.5%) |

215 (91.9%) |

||

|

Missing |

3 (0.3%) |

2 (0.3%) |

1 (0.4%) |

||

|

Birthweight (grams) |

0.03b |

||||

|

<2500 |

70 (7.1%) |

57 (7.5%) |

13 (5.6%) |

||

|

2500 |

873 (87.9%) |

671 (88.4%) |

202 (86.3%) |

||

|

Missing |

50 (5.0%) |

31 (4.1%) |

19 (8.1%) |

||

|

Neonatal Sex |

0.20b |

||||

|

Male |

530 (53.4%) |

401 (55.1%) |

129 (60.0%) |

||

|

Female |

413 (41.6%) |

327 (44.9%) |

86 (40.0%) |

||

|

Missing |

50 (5.0%) |

* |

* |

||

|

Multiple Gestation |

0.02b |

||||

|

Yes |

945 (95.2%) |

729 (96.1%) |

216 (92.3%) |

||

|

No |

48 (4.8%) |

30 (3.9%) |

18 (7.7%) |

||

|

Missing |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

||

a: Fisher’s Exact test

b: Chi-squared test

c: Mann-Whitney U test

*unknown mode of delivery for missing data

Notes: Categories for duration of labor were chosen by study team and not per a reference article; we suspect the 1 woman who reportedly underwent cesarean birth without anesthesia is likely an erroneous data point; an Integrated Emergency Surgical Officer is a non-physician surgeon in the Ethiopian surgical workforce; missing data not included in bivariate comparisons and chi-squared testing was used for cell sizes above 5.

Table 2: Antepartum, Labor, and Delivery Characteristics of Women by Mode of Delivery.

|

Characteristic |

Overall Population |

Bivariate Comparisons |

|||

|

N (%) N = 993 |

Vaginal Birth (n = 759, 75.9%) |

Cesarean Birth (n = 234, 23.4%) |

P-Value |

||

|

Postpartum Maternal Interventions and/or Complications |

|||||

|

Postpartum Blood Transfusion |

<0.001a |

||||

|

No |

976 (98.3%) |

755 (99.5%) |

221 (94.4%) |

||

|

Yes |

15 (1.5%) |

4 (0.5%) |

11 (4.7%) |

||

|

Missing |

2 (0.2%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (0.9%) |

||

|

Postpartum Antibiotics |

<0.001b |

||||

|

No |

900 (90.6%) |

740 (97.5%) |

160 (68.4%) |

||

|

Yes |

88 (8.9%) |

17 (2.2%) |

71 (30.3%) |

||

|

Missing |

5 (0.5%) |

2 (0.3%) |

3 (1.3%) |

||

|

Postpartum Hypertensive Treatment |

0.04b |

||||

|

No |

967 (97.4%) |

741 (97.6%) |

226 (96.6%) |

||

|

Yes |

24 (2.4%) |

18 (2.4%) |

6 (2.6%) |

||

|

Missing |

2 (0.2%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (0.9%) |

||

|

Postpartum Anticonvulsant Treatment |

0.05a |

||||

|

No |

965 (97.2%) |

737 (97.1%) |

228 (97.4%) |

||

|

Yes |

26 (2.6%) |

22 (2.9%) |

4 (1.7%) |

||

|

Missing |

2 (0.2%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (0.9%) |

||

|

Maternal Length of Hospitalization Median (IQR) |

1 [1, 3] |

1 [1, 1] |

3 [3, 4] |

<0.001c |

|

|

Missing |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

||

|

Neonatal Interventions and/or Complications |

<0.001c |

||||

|

Five-Minute Apgar Score Median (IQR) |

9 [8, 9] |

9 [8, 9] |

8 [7, 9] |

||

|

Missing |

45 (4.5%) |

30 (3.0%) |

18 (1.8%) |

||

|

Stillbirth |

0.001a |

||||

|

Yes, Fresh |

29 (2.9%) |

15 (2.0%) |

14 (6.0%) |

||

|

Yes, Macerated |

12 (1.2%) |

11 (1.5%) |

1 (0.4%) |

||

|

No |

903 (90.9%) |

702 (92.5%) |

201 (85.9%) |

||

|

Missing |

49 (4.9%) |

31 (4.1%) |

18 (7.7%) |

||

|

Bag & Mask Resuscitation |

0.79a |

||||

|

No |

977 (98.4%) |

746 (98.3%) |

231 (98.7%) |

||

|

Yes |

12 (1.2%) |

9 (1.2%) |

3 (1.3%) |

||

|

Missing |

4 (0.4%) |

4 (0.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

||

|

Intranasal Oxygen |

0.79a |

||||

|

No |

970 (97.7%) |

740 (97.5%) |

230 (98.3%) |

||

|

Yes |

20 (2.0%) |

16 (2.1%) |

4 (1.7%) |

||

|

Missing |

3 (0.3%) |

3 (0.4%) |

0 (0.0%) |

||

|

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) |

0.18a |

||||

|

No |

980 (97.7%) |

750 (98.8%) |

230 (98.3%) |

||

|

Yes |

9 (2.0%) |

5 (0.7%) |

4 (1.7%) |

||

|

Missing |

4 (0.3%) |

4 (0.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

||

|

Intravenous Fluid Administration |

0.18b |

||||

|

No |

959 (96.6%) |

731 (96.3%) |

228 (97.4%) |

||

|

Yes |

31 (3.1%) |

25 (3.3%) |

6 (2.6%) |

||

|

Missing |

3 (0.3%) |

3 (0.4%) |

0 (0.0%) |

||

|

Antibiotics |

0.85b |

||||

|

No |

952 (95.9%) |

727 (95.8%) |

225 (96.2%) |

||

|

Yes |

34 (3.4%) |

26 (3.4%) |

8 (3.4%) |

||

|

Missing |

7 (0.7%) |

6 (0.8%) |

1 (0.4%) |

||

|

Blood Transfusion |

1.0a |

||||

|

No |

982 (98.9%) |

756 (98.8%) |

232 (99.2%) |

||

|

Yes |

4 (0.4%) |

2 (0.4%) |

1 (0.4%) |

||

|

Missing |

7 (0.7%) |

1 (0.8%) |

1 (0.4%) |

||

|

Neonate Status on Day of Discharge |

0.07b |

||||

|

Dead* |

55 (5.5%) |

35 (4.6%) |

20 (8.6%) |

||

|

Alive |

933 (94.0%) |

720 (94.9%) |

213 (91.0%) |

||

|

Missing |

5 (0.5%) |

4 (0.5%) |

1 (0.4%) |

||

|

Neonatal Length of Hospitalization, Median (IQR) |

1 [1, 3] |

1 [1, 1] |

3 [3, 4] |

<0.001c |

|

|

Missing |

20 (2.0%) |

13 (1.7%) |

7 (3.0%) |

||

a: Fisher’s Exact test

b: Chi-squared test

c: Mann-Whitney U test

*Total number dead, including stillbirths

Note: missing data were not included in bivariate comparisons, and chi-squared testing was used for cell sizes above 5

Table 3: Postpartum Interventions and/or Complications of Women and Infants by Mode of Delivery.

|

Characteristic |

RR |

CI |

P-Value |

|

(A) Multivariable Poisson Model with Robust Error Variance of Characteristics Associated with Cesarean Birth* |

|||

|

History of Cesarean Birth |

2.0 |

1.5, 2.7 |

<0.001 |

|

Transferred in Labor |

1.5 |

1.1, 1.9 |

0.003 |

|

Increased Cervical Dilation on Admission |

0.9 |

0.9, 0.9 |

<0.001 |

|

Compared to Less Than 12 hours of Labor: |

|||

|

12 – 24 hours |

1.3 |

1.1, 1.9 |

0.03 |

|

> 24 hours |

2.7 |

1.8, 3.9 |

<0.001 |

|

Compared to Non-Use of the Partograph: |

|||

|

Complete Use |

0.6 |

0.4, 0.9 |

0.03 |

|

Birthweight 2500 |

2.7 |

1.5, 4.8 |

0.001 |

|

(B) Individual Multivariable Poisson Models with Robust Error Variance, Adjusted for Significant Findings in Table 4A, to Determine Association of Cesarean Birth with Outcomes Significant in Bivariate Comparisons (Table 3) |

|||

|

Characteristic |

RR |

CI |

P-Value |

|

Maternal Outcomes |

|||

|

Needing Maternal Blood Transfusion |

3.2 |

0.7, 14.0 |

0.1 |

|

Needing Postpartum Antibiotics |

10.5 |

6.1, 18.1 |

<0.001 |

|

Needing Postpartum Hypertensive Therapy |

1.1 |

0.3, 3.3 |

0.9 |

|

Needing Postpartum Anticonvulsant Therapy |

0.4 |

0.1, 1.7 |

0.2 |

|

Neonatal Outcomes |

|||

|

Having a Higher Apgar Score |

0.9 |

0.9, 0.98 |

0.01 |

|

Live Birth |

1.0 |

0.9, 1.1 |

0.6 |

|

Being Alive at Discharge from the Hospital |

1.0 |

0.9, 1.1 |

0.7 |

*variables included in the model without an association with the outcome: age, urban/rural residence, parity, onset of labor (spontaneous or not), incomplete partograph use, number of vaginal exams, antepartum hemorrhage, number of fetuses delivered

Table 4: A) Multivariable Model of Characteristics Associated with Cesarean Birth and; B) How Outcomes are Impacted by Undergoing Cesarean Birth.

4. Discussion

In summary, in our cross-sectional analysis of a convenience, consecutive sample of 1000 women who gave birth at MTUTH, we found that cesarean birth was prevalent (23.4%) in the 993 women with data on mode of birth, was more common in labors with complications (transfer, bleeding, prolongation), and in settings where it was used, maternal (bleeding, infection) and neonatal (lower 5-minute Apgar, fresh stillbirth) complications were more prevalent. Notable findings included the higher rate of cesarean birth among women from urban areas and the high prevalence of fresh stillbirths (compared to macerated) among cesarean as compared to vaginal births. Regarding the finding of a higher prevalence of cesarean birth among women living in urban areas, which for the purposes of this analysis represents the Mizan-Aman town from which about 45.0% of the population hails (data not shown), this is a common finding in the literature [11, 12]. Further analysis is needed comparing urban versus rural women undergoing cesarean birth in terms of pregnancy outcomes. If the rate of cesarean among urban women is higher without a resultant improvement in adverse outcomes such as stillbirth, the higher rate represents an unclear benefit. Conversely, if women in rural areas are experiencing more adverse outcomes with a lower cesarean birth rate, this would represent an unmet need for cesarean where a higher cesarean birth rate in this subgroup might contribute to improved outcomes. Though the overall rate of HIV positivity is low in the cohort (although higher than overall national estimates), it is notable that the mode of birth does not vary by HIV status [13]. More investigation into whether this is because pregnant women living with HIV are well-controlled with a low viral load that does not prohibit vaginal birth, or if it is because women were managed according to their obstetric indications for cesarean birth and not their HIV status, is warranted. This might be an area to pursue additional qualitative or survey research to understand how pregnant women living with HIV are managed in this setting.

Regarding obstetrical complications associated with cesarean birth, it is consistent with international literature that women with a history of cesarean birth, those transferred during labor, women admitted in early labor, and those with a prolonged labor course were more likely to experience cesarean birth [14-20]. What is less clear is the result suggesting that completion of the partograph (compared to non-use), reduced the risk of cesarean birth. We wonder if this is a spurious association, which might represent the fact that for women undergoing cesarean birth, their partograph was not used because they either had a truncated or nonexistent labor course. However, we feel it safe to recommend complete and high-quality use of the partograph given recent literature showing it reduces the rate of stillbirth (an adverse outcome common in this facility) [21]. It is well-known that women requiring cesarean birth experience more adverse outcomes than women undergoing vaginal birth [2, 5, 7, 8, 18, 22-24]. Cesarean birth is a major abdominal surgery that can result in adverse outcomes in itself, but it does follow logically that women with prolonged labor courses that required transfer who may have larger babies are more likely to experience labor dystocia, which might contribute to increased adverse outcomes. However, the finding that cesarean birth was associated with an increased risk of antibiotic use and not hemorrhage, for example, may support the known literature that endometritis is more common after cesarean than vaginal birth [25]. It is a limitation of this analysis that we did not define and observe sepsis rates, as in some settings it is standard practice for administration of postpartum prophylactic antibiotics so we do not know if this finding represents true infection [10]. A 6.0% rate of fresh stillbirth is concerning, but given our study was not designed to look at this outcome specifically, it is hard to draw and conclusions regarding the outcome. However, we would consider fresh stillbirth a modifiable risk factor. Intermittent fetal auscultation is a low-resource, low-complexity technology that the WHO has recommend during labor to monitor the fetal status [26, 27]. In light of the high stillbirth rate, this WHO recommendation may be indicated to ensure cesarean birth is used as a fetal life-saving measure when medically indicated [21]. MTUTH could consider a qualitative intervention to improve monitoring of laboring women or designing a prospective study to determine the root causes of stillbirth and any role under-monitoring might play.

This study is limited by the convenience, consecutive sampling technique and the variables selected for inclusion. The study sample may have been biased towards a population of women desiring to deliver in a facility or with high health-seeking behavior. The variables included those the study authors felt were relevant to labor and delivery care based on the literature and their own experience but may have neglected to include some other practitioners in the field consider to be relevant. For example, body mass index was not included, which would have been an informative variable, and given our finding about postpartum antibiotics, it would have been important to know whether they were administered prophylactically or for a confirmed diagnosis of postpartum endometritis. Strengths of the study include the large sample size and high-quality data collection by physicians with an intimate understanding of labor and delivery care.

5. Conclusion

In summary, cesarean birth appears to be being used at MTUTH in cases of labor complications (prolonged labor or transfer), which are medical indications. In this cohort, according to our analytic methods, there were minimal complications attributable to the procedure itself suggesting that high-quality cesareans are being performed at MTUTH. More research on the prevalence of stillbirth in this facility is warranted.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relationships to disclose that may be deemed to influence the objectivity of this paper and its review. The authors report no commercial associations, either directly or through immediate family, in areas such as expert testimony, consulting, honoraria, stock holdings, equity interest, ownership, patent-licensing situations or employment that might pose aconflict of interest to this analysis. Additionally, the authors have no conflicts such as personal relationships or academic competition to disclose. The findings presented in this paper represent the views of the named authors only, and not the views of their institutions or organizations.

Funding

Funding for this project comes primarily from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation with additional support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development Women’s Reproductive Health Research K12 award of the primary author (5K12HD001271).

Data Availability

De-identified data will be considered for availability under a data use agreement.

Author Contributions

EK, BT, TW designed the data collection forms with MSH and collected the data under the supervision of TY and MM. AJZ managed the data and provided quality checks. MSH conceived of the analytic plan, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript with feedback from all authors.

References

- Betran AP, Torloni MR, Zhang J, et al. What is the optimal rate of caesarean section at population level? A systematic review of ecologic studies. Reprod Health 12 (2015): 57.

- Betran AP, Torloni MR, Zhang JJ, et al. WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates. Bjog 123 (2016): 667-670.

- Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, et al. The Increasing Trend in Caesarean Section Rates: Global, Regional and National Estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS One 11 (2016): e0148343.

- Gibbons L, Belizan JM, Lauer JA, et al. Inequities in the use of cesarean section deliveries in the world. Am J Obstet Gynecol 206 (2012): 331.e331-331.e319.

- Betran AP, Temmerman M, Kingdon C, et al. Interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections in healthy women and babies. Lancet 392 (2018): 1358-1368.

- Boatin AA, Schlotheuber A, Betran AP, et al. Within country inequalities in caesarean section rates: observational study of 72 low and middle income countries. Bmj 360 (2018): k55.

- Harrison MS, Goldenberg RL. Cesarean section in sub-Saharan Africa 2 (2016).

- Harrison MS, Pasha O, Saleem S, et al. A prospective study of maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes in the setting of cesarean section in low- and middle-income countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 96 (2017): 410-420.

- REDCap (2019).

- Organization WH. WHO recommendations for prevention and treatment of maternal peripartum infections. World Health Organization (2016).

- Fesseha N, Getachew A, Hiluf M, et al. A national review of cesarean delivery in Ethiopia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 115 (2011): 106-111.

- Yisma E, Smithers LG, Lynch JW, et al. Cesarean section in Ethiopia: prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 32 (2019): 1130-1135.

- Ethiopia Country Profile (2019).

- Vogel JP, Betrán AP, Vindevoghel N, et al. Use of the Robson classification to assess caesarean section trends in 21 countries: a secondary analysis of two WHO multicountry surveys 3 (2015): e260-e270.

- Betran AP, Gulmezoglu AM, Robson M, et al. WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America: classifying caesarean sections. Reprod Health 6 (2009): 18.

- Harrison MS. Method of birth in nulliparous women with single, cephalic, term pregnancies: the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health, 2004 – 2008 In. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2019).

- Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Gülmezoglu AM, et al. Method of delivery and pregnancy outcomes in Asia: the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health 2007–08. The Lancet 375 (2010): 490-499.

- Shah A, Fawole B, M'Imunya JM, et al. Cesarean delivery outcomes from the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Africa. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 107 (2009): 191-197.

- Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla D, et al. Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. The Lancet 367 (2006): 1819-1829.

- Ganchimeg T, Nagata C, Vogel JP, et al. Optimal Timing of Delivery among Low-Risk Women with Prior Caesarean Section: A Secondary Analysis of the WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. PLOS ONE 11 (2016): e0149091.

- Housseine N, Punt MC, Browne JL, et al. Strategies for intrapartum foetal surveillance in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLOS ONE 13 (2018): e0206295.

- Abebe Eyowas F, Negasi AK, Aynalem GE, et al. Adverse birth outcome: a comparative analysis between cesarean section and vaginal delivery at Felegehiwot Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective record review. Pediatric Health Med Ther 7 (2016):65-70.

- Gibson K BJ. Cesarean delivery as a marker for obstetric quality. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 58 (2015): 211-216.

- Woldeyes WS, Asefa D, Muleta G. Incidence and determinants of severe maternal outcome in Jimma University teaching hospital, south-West Ethiopia: a prospective cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18 (2018): 255.

- Bauer ME, Housey M, Bauer ST, et al. Risk Factors, Etiologies, and Screening Tools for Sepsis in Pregnant Women: A Multicenter Case-Control Study. Anesth Analg 129 (2019): 1613-1620.

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience (2018): 1-210.

- World Health Organization. WHO safe childbirth checklist implementation guide: improving the quality of facility-based delivery for mothers and newborns (2015).

Appendix:

Degrees of Freedom, Test Statistic, and Cramer’s V for Each Covariate

|

Characteristic |

Degrees of Freedom |

Test Statistic |

Cramer’s V Test of Correlation with Mode of Birth |

|

Age |

- |

Z = -1.9 |

0.1 |

|

Education |

5 |

3.1 |

0.06 |

|

Religion |

1 |

13.9 |

-0.1 |

|

Relationship Status |

2 |

1.5 |

0.5 |

|

Woreda |

2 |

1.6 |

0.04 |

|

Parity |

6 |

12.1 |

0.06 |

|

Months Since Last Delivery (parity 1+ n = 572) |

- |

Z = 0.5 |

0.2 |

|

Gestational Age Determination |

2 |

2.29 |

0.05 |

|

History of Cesarean Birth |

2 |

55.2 |

0.2 |

|

HIV+ |

1 |

2.3 |

-0.04 |

|

Number of Prenatal Visits |

- |

Z = -0.9 |

0.2 |

a: Mann Whitney U test; b: Fisher’s Exact test; c: Chi-squared test

|

Characteristic |

Degrees of Freedom |

Test Statistic |

Cramer’s V Test of Corre-lation with Mode of Birth |

|

Onset of Labor |

2 |

70.0 |

0.3 |

|

Transferred During Labor |

1 |

20.3 |

0.1 |

|

If Transferred, Transferring Facility (Transferred n = 481) |

2 |

0.02 |

0.007 |

|

Cervical Exam on Admission |

- |

Z = 2.73 |

0.2 |

|

Fetal Heart Rate Auscultated at Admission |

2 |

0.9 |

0.03 |

|

Duration of Labor |

3 |

94.3 |

0.3 |

|

Partograph Used |

3 |

162.4 |

0.4 |

|

Number of Vaginal Exams |

- |

Z = 4.5 |

0.4 |

|

Antepartum Hemorrhage |

1 |

6.0 |

0.08 |

|

Chorioamnionitis |

1 |

0.3 |

0.02 |

|

Antepartum Pre-eclampsia/Eclampsia/ Chronic Hypertension |

1 |

0.5 |

0.02 |

|

Anesthesia for Birth |

1 |

632.8 |

0.8 |

|

Delivery Provider |

3 |

874.3 |

0.9 |

|

Gestational Age at Delivery |

- |

Z = -2.3 |

0.1 |

|

Birthweight (grams) |

- |

Z = -3.1 |

0.3 |

|

Neonatal Sex |

1 |

1.6 |

-0.04 |

|

Multiple Gestation |

1 |

5.4 |

0.07 |

a: Fisher’s Exact test; b: Chi-squared test; c: Mann-Whitney U test

|

Characteristic |

Degrees of Freedom |

Test Statistic |

Cramer’s V Test of Correlation with Mode of Birth |

|

Postpartum Blood Transfusion |

1 |

1.2 |

-0.03 |

|

Postpartum Antibiotics |

1 |

0.6 |

-0.02 |

|

Postpartum Hypertensive Treatment |

1 |

0.03 |

0.006 |

|

Postpartum Anticonvulsant Treatment |

1 |

1.0 |

-0.03 |

|

Maternal Length of Hospitalization |

- |

Z = -25.1 |

0.8 |

|

Five-Minute Apgar Score |

- |

Z = 8.7 |

0.4 |

|

Stillbirth |

2 |

12.2 |

0.1 |

|

Bag & Mask Resuscitation |

1 |

0.01 |

0.004 |

|

Intranasal Oxygen |

1 |

0.1 |

-0.01 |

|

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) |

1 |

2.2 |

0.05 |

|

Intravenous Fluid Administration |

1 |

0.3 |

-0.01 |

|

Antibiotics |

1 |

<0.001 |

< - 0.001 |

|

Blood Transfusion |

1 |

0.004 |

0.002 |

|

Neonate Status on Day of Discharge |

1 |

5.3 |

-0.07 |

|

Neonatal Length of Hospitalization |

- |

Z = -21.5 |

0.8 |

a: Fisher’s Exact test; b: Chi-squared test; c: Mann-Whitney U test