Age As A Risk Factor of Trauma in the Greek Female Population

Article Information

Antonopoulou Christina*

Professor, Athens University, Greece

*Corresponding Author: Dr. Antonopoulou Christina, Professor, Athens University, Greece

Received: 03 April 2019; Accepted: 10 April 2019; Published: 06 May 2019

Citation: Antonopoulou Christina. Age As A Risk Factor of Trauma in the Greek Female Population. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Disorders 3 (2019): 102-112.

Share at FacebookAbstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the frequency of trauma among Greek women, ages 20-55. Twenty six Greek females completed the TSI (John Briere), MDI (John Pierce), and DAPS (John Briere) questionnaires. A one way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was computed to determine whether age is a risk factor in the occurrence of trauma. Significant results were found in many items of each questionnaire, suggesting that the older a woman is the more likely she has experienced a traumatic event, and has been affected by it. For example, item #5 of the DAPS “Someone threatening to injure you or to do something sexual to you against your will, although they didn’t actually do anything to you, when you were afraid you would be hurt or killed?” was found to be significant (F=4,82 p<0,026) indicating that women 40 and up responded yes more often than women under 40. However, on the MDI women ages 30 to 40 scored higher, depicting dissociative qualities which lead us to assume that traumatic events occurred more recently in these women. Furthermore, we can infer that women in their 40’s and up continue to experience traumatic events, however have developed ways to cope “learned helplessness” with these negative experiences. Perhaps this is why women 40 and up show symptoms of depression and anxiety more often, while women in their 30’s display more often signs of acute traumatic dissociative qualities. Supporting our hypothesis are items on the MDI such as item #2 “Your body feeling like it was somebody else’s” (F=3,36 p<0,05) which was responded to most often by women in their 30’s.

Keywords

Trauma, Post traumatic stress disorder, Psychiatric, Psychological

Trauma articles Trauma Research articles Trauma review articles Trauma PubMed articles Trauma PubMed Central articles Trauma 2023 articles Trauma 2024 articles Trauma Scopus articles Trauma impact factor journals Trauma Scopus journals Trauma PubMed journals Trauma medical journals Trauma free journals Trauma best journals Trauma top journals Trauma free medical journals Trauma famous journals Trauma Google Scholar indexed journals Post traumatic stress disorder articles Post traumatic stress disorder Research articles Post traumatic stress disorder review articles Post traumatic stress disorder PubMed articles Post traumatic stress disorder PubMed Central articles Post traumatic stress disorder 2023 articles Post traumatic stress disorder 2024 articles Post traumatic stress disorder Scopus articles Post traumatic stress disorder impact factor journals Post traumatic stress disorder Scopus journals Post traumatic stress disorder PubMed journals Post traumatic stress disorder medical journals Post traumatic stress disorder free journals Post traumatic stress disorder best journals Post traumatic stress disorder top journals Post traumatic stress disorder free medical journals Post traumatic stress disorder famous journals Post traumatic stress disorder Google Scholar indexed journals Psychiatric articles Psychiatric Research articles Psychiatric review articles Psychiatric PubMed articles Psychiatric PubMed Central articles Psychiatric 2023 articles Psychiatric 2024 articles Psychiatric Scopus articles Psychiatric impact factor journals Psychiatric Scopus journals Psychiatric PubMed journals Psychiatric medical journals Psychiatric free journals Psychiatric best journals Psychiatric top journals Psychiatric free medical journals Psychiatric famous journals Psychiatric Google Scholar indexed journals Psychological articles Psychological Research articles Psychological review articles Psychological PubMed articles Psychological PubMed Central articles Psychological 2023 articles Psychological 2024 articles Psychological Scopus articles Psychological impact factor journals Psychological Scopus journals Psychological PubMed journals Psychological medical journals Psychological free journals Psychological best journals Psychological top journals Psychological free medical journals Psychological famous journals Psychological Google Scholar indexed journals anxiety disorders articles anxiety disorders Research articles anxiety disorders review articles anxiety disorders PubMed articles anxiety disorders PubMed Central articles anxiety disorders 2023 articles anxiety disorders 2024 articles anxiety disorders Scopus articles anxiety disorders impact factor journals anxiety disorders Scopus journals anxiety disorders PubMed journals anxiety disorders medical journals anxiety disorders free journals anxiety disorders best journals anxiety disorders top journals anxiety disorders free medical journals anxiety disorders famous journals anxiety disorders Google Scholar indexed journals depression articles depression Research articles depression review articles depression PubMed articles depression PubMed Central articles depression 2023 articles depression 2024 articles depression Scopus articles depression impact factor journals depression Scopus journals depression PubMed journals depression medical journals depression free journals depression best journals depression top journals depression free medical journals depression famous journals depression Google Scholar indexed journals psychodynamic theory articles psychodynamic theory Research articles psychodynamic theory review articles psychodynamic theory PubMed articles psychodynamic theory PubMed Central articles psychodynamic theory 2023 articles psychodynamic theory 2024 articles psychodynamic theory Scopus articles psychodynamic theory impact factor journals psychodynamic theory Scopus journals psychodynamic theory PubMed journals psychodynamic theory medical journals psychodynamic theory free journals psychodynamic theory best journals psychodynamic theory top journals psychodynamic theory free medical journals psychodynamic theory famous journals psychodynamic theory Google Scholar indexed journals psychologically traumatized articles psychologically traumatized Research articles psychologically traumatized review articles psychologically traumatized PubMed articles psychologically traumatized PubMed Central articles psychologically traumatized 2023 articles psychologically traumatized 2024 articles psychologically traumatized Scopus articles psychologically traumatized impact factor journals psychologically traumatized Scopus journals psychologically traumatized PubMed journals psychologically traumatized medical journals psychologically traumatized free journals psychologically traumatized best journals psychologically traumatized top journals psychologically traumatized free medical journals psychologically traumatized famous journals psychologically traumatized Google Scholar indexed journals hypersensitivity articles hypersensitivity Research articles hypersensitivity review articles hypersensitivity PubMed articles hypersensitivity PubMed Central articles hypersensitivity 2023 articles hypersensitivity 2024 articles hypersensitivity Scopus articles hypersensitivity impact factor journals hypersensitivity Scopus journals hypersensitivity PubMed journals hypersensitivity medical journals hypersensitivity free journals hypersensitivity best journals hypersensitivity top journals hypersensitivity free medical journals hypersensitivity famous journals hypersensitivity Google Scholar indexed journals emotional arousal articles emotional arousal Research articles emotional arousal review articles emotional arousal PubMed articles emotional arousal PubMed Central articles emotional arousal 2023 articles emotional arousal 2024 articles emotional arousal Scopus articles emotional arousal impact factor journals emotional arousal Scopus journals emotional arousal PubMed journals emotional arousal medical journals emotional arousal free journals emotional arousal best journals emotional arousal top journals emotional arousal free medical journals emotional arousal famous journals emotional arousal Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

1. Introduction

Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) first received official recognition in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-III, 1980), in which it was placed among the anxiety disorders. Like other the disorders in the DSM, PTSD is defined by a cluster of symptoms. However, unlike the other disorders in the DSM, PTSD includes part of its assumed etiology, namely a traumatic event or events that the person has, directly experienced or witnessed involving actual or threatened death, or serious injury to self or others. PTSD entails an extreme response to the severe stressor which must have created intense fear, horror, or a sense of helplessness. The person’s response must also include increased anxiety, avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, and numbing of emotional responses (DSM-IV-TR, 2000). This disorder carries risks of chronicity, morbidity, mortality, and greater physical and psychiatric impairment or disturbance in interpersonal and professional functioning. Living in times of war, natural disaster, domestic violence, and trafficking, it is no surprise that the prevalence of PTSD is on the rise.

Both psychological and biological theories have been proposed to account for PTSD. Learning theorists assume that the disorder arises from a classical conditioning of fear [1, 2]. There is a body of evidence in support of this view Foy et al. [3] and of the related cognitive-behavioral theories that emphasize the loss of control and predictability felt by PTSD sufferers, such as victims of spousal abuse [4, 5]. A psychodynamic theory proposed by Horowitz [6] posits that memories of the traumatic event occur constantly in the person’s mind and are so painful that they are either consciously suppressed or repressed. The person is believed to engage in a kind of internal struggle to integrate the trauma into his or her existing beliefs about him or herself and the world to make some sense out of it.

More recently, a biological diathesis has been suggested. Bessel van der Kolk [7 ], the leader in this area, has found that chronic stress due to trauma has a psychobiological impact on an individual. Not only is the person psychologically traumatized but the physical organism is permanently altered as well. Chronically stressed organisms have lower levels of serotonin at rest and when stressed. Low serotonin is associated with irritability, hypersensitivity, and exaggerated emotional arousal to relatively mild stimuli; all of which are symptoms of PTSD (1996). This is nicely illustrated by an experiment on exaggerated startle response conducted by Shalev et al. [8]. In this study, the researchers created a louse noise at random times in a room full of people. At first everyone jumped at the loud noise. The second time the noise came, most people jumped. By the third time the noise sounded, most people in the room who had not experienced any trauma had gotten used to the noise and did not jump. However, 93% of the trauma survivors continued to jump each time the noise sounded even though they figured that another noise was likely to happen.

No matter what theoretical orientation one takes to explain its etiology, all mental health professionals can agree that the symptoms of PTSD are adaptations to traumatic experiences. In the past few years, prospective studies have emerged examining various traumatized populations that have shed light on the course of PTSD. Furthermore, studies have been conducted that have established that different populations may develop symptoms of PTSD caused by trauma without actually meeting all of the criteria in the DSM-IV-TR. People may adapt and deal with a trauma by developing a variety of symptoms that seem most suited to them, as how one perceives and incorporates trauma into one’s life is highly subjective. The importance of subjective perception is illustrated by a report from Pilowsky [9] who described the emergence of PTSD-like symptoms in accident victims whose perception of danger far exceeded the actual risks. Other people may deal with trauma by developing different parenting behaviors as their primary adaptation Mowder et al. [10] as opposed to developing pathological symptoms. Lastly, symptoms may be manifested and expressed differently from culture to culture as cultural practices and life greatly influences one’s subjective experience.

Several risk factors have been identified for the development of PTSD. In the Breslau et al. [11] study, predictors of PTSD, given exposure to a traumatic event, was being female, early separation from parents, family history of a disorder, and a preexisting disorder. The likelihood of developing PTSD also increases with the severity of the traumatic event. The initial reaction to the trauma is also predictive. More severe anxiety, depression, and dissociative symptoms (including depersonalization, derealization, amnesia, and out-of-body experiences) all increase the probability of later developing PTSD [8]. Thus, certain populations with these risk factors may exhibit PTSD symptoms more frequently and more intensely than other populations who do not have these factors. It is important for all mental health practitioners to be made aware of the risk factors for developing PTSD, so that appropriate prevention methods may be implemented and available to these “at risk” populations before the onset of PTSD occurs.

One factor that has not been considered in the development of PTSD symptoms is age. Just as various populations may exhibit particular symptoms of PTSD, different age groups may also manifest different signs of trauma, and specific types of symptoms may be more prevalent in certain age clusters than in others. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine in depth the signs and symptoms of trauma within three age groups in the general Greek female population to determine whether signs of trauma exist in each age group, and whether or not these signs differ and or are more prevalent from group to group. These age groups are, women from 20 to 30, women from 30 to 40, and women 40 and up.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

There were 26 participants, ages 20 to 65. All participants were Greek females recruited voluntarily from various regions of Greece. None of the participants were compensated for their participation in the study and all of the participants gave informed consent to participate.

2.2 Materials

Three self-report questionnaires were used in this study, the TSI, the DAPS, and the MDI. The Trauma Syndrome Inventory – TSI (Briere, J), consists of 100 items and is in Likert’s Scale format from 0 to 3. The MDI (Pierce, J) consists of 30 items, also in Likert’s format from 1 to 5, and the DAPS (Briere, J) consists of 104 items with a Likert’s scale format from 1 to 5. All three measures have been shown to possess significantly construct validity and reliability.

2.3 Procedure

All of the participants were read the instructions and items of the TSI, MDI, and DAPS questionnaires. Some participants chose to read the questionnaires’ items on their own. All of the participants completed all 100 items of the TSI, 30 items of the MDI, and 104 items of the DAPS. They were all given as much time as needed. The participants responded to each item on the TSI’s Likert’s Scale by circling a number from 0 to 3. Zero was circled if the participant did not have the experience described in the item in the last six months, 1 or 2 if the participant sometimes experienced what the item described in the last six months, and 3 if the participant frequently had such an experience in the last six months.

The MDI also had a Likert's Scale for the participants’ responses. The MDI’s scale consisted of numbers 1 to 5, one meaning that the participant did not had the experience described in the item in the last month. Two was circled if the participant had the experience once or twice, 3 if a few times, 4 if often, and 5 if frequently in the last month. Lastly, the DAPS consisted of a Likert’s Scale exactly like the MDI’s. However, some of the questions on the DAPS asked the participants, whether or not they had certain experiences at any point in their lives, while other questions referred to experiences that may or may not have occurred within the last month.

2.4 Data coding

Despite the differences in their Likert’s Scales, both the responses for the TSI and the MDI were coded in the same way so that they could be compared. Responses of never in the last six months (0) on the TSI were coded as 0, while responses for sometimes (1, 2) were coded as 1. Responses to frequently in the last six months (3) were coded as 2. For the MDI, responses of never in the last month (1) were coded as 0, while responses for both once or twice in the last month (2) and a few times in the last month (3) were coded as 1. Lastly, both responses for often in the last month (4) and frequently in the last month (5) were coded as 2.

Responses for never (1) on the DAPS were coded as 0. In addition, responses for both once or twice (2) and sometimes (3) were coded as 1, while responses to frequently (4) and very frequent (5) were coded as 2 on the DAPS. The only item on the DAPS that was coded differently was item number 14. This item was coded with the number which corresponds to the experience that the participant chose to describe. For example, if a participant described and earthquake, number 14 was coded as 2 since item number 2 asks whether or not the participant ever experienced an earthquake. Ages of the participants were coded as 1 for women in their twenties, 2 if the women were in their thirties and 3 if they were in their forties and up.

3. Results

Significant differences were found between the different age groups on all three questionnaires. The women in their twenties showed no significant signs or symptoms of trauma. However, significant differences were found on many individual items of each questionnaire across the three age groups, indicating that the two age groups which did exhibit signs and symptoms of trauma differed in the frequency and nature of each symptom. Furthermore, each age group’s responses to each one and across the questionnaires were consistent and reliable. A two-tailed Pearson correlation was conducted and yielded a significant correlation, r =0.62, p < 0.01, between the participants’ responses on the TSI and their responses on the MDI. The mean scores on the TSI for the participants in their twenties, thirties, and forties were 0.55 (0.21), 0.53 (0.27), and 0.70 (0.15), respectively. A split-half reliability was also conducted for the TSI indicating a significant reliability of 0.86. In order, means scores on the MDI for the participants in their twenties, thirties, and forties were 0.20, 0.42, and 0.27 (SDs = 0.12, 29, and 0.15, respectively). The mean scores on the DAPS for the participants in their twenties, thirties, and forties were 0.29 (0.16), 0.39 (0.29), and 0.47 (0.15), respectively.

A one way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was computed to determine whether age is a significant factor in the participants’ responses to each item of the TSI and the MDI. The significance level was set at a standard of 0.05. For the TSI, significant results were found for items 2 (F= 5.00, p < 0.015), 4 (F= 4.69, p < 0.019), 26 (F= 7.47, p < 0.003), 32 (F= 3.57, p < 0.04), 52 (F= 5.60, p < 0.01, and 78 (F= 3.94, p < 0.032) respectively. In addition, significant results were yielded on the MDI for items 2 (F= 3.36, p < 0.05), 8 (F= 3.36, p < 0.05), 9 (F= 6.06, p < 0.008), 15 (F= 3.36, p < 0.05), 19 (F= 3.27, p < 0.05), 20 (F= 3.32, p < 0.05), 21 (F= 3.36, p < 0.05), 22 (F= 7.8, p < 0.003), and 30 (F= 3.78, p < 0.038) respectively. The experiences depicted by the items found to be significant by the one way ANOVA include, “trying to forget past unpleasant periods in life, feeling empty inside, feeling as if you are outside of your own body, being confused about sexual feelings, having problems with a sex partner, and not being able to identify feeling emotions, among others”. A one way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was also conducted for the DAPS, yielding significant results for certain items. In order, the items found to be significant were 5 (F= 6.02, p < 0.008), 88 (F= 4.42, p < 0.024), and 95 (F= 8.84, p < 0.001).

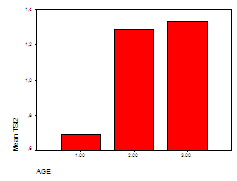

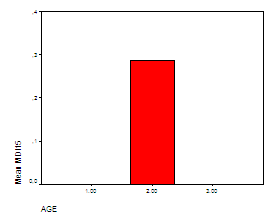

The bar graphs representing the significant items on the TSI, MDI, and DAPS clearly depict discrepancies in the responses between the three age groups. In the TSI, the general pattern is that the older the woman, the more frequently she has had certain avoidance experiences, for example, “trying to forget unpleasant moments from the past” (item 2).

Graph 1: The general pattern TSI, the older the woman, the more frequently she has had certain avoidance experiences.

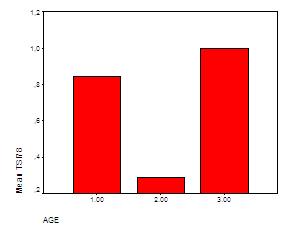

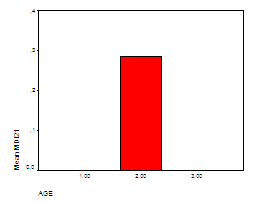

The significant items on the TSI that do not follow this general pattern, follow another consistent pattern where the women in their 20’s and 40’s indicate having had certain experiences, quite frequently while the women in their 30’s indicating rarely having had the same exact experiences. An example of such an experience is, “Trying to avoid being alone” (item 78).

Graph 2: The significant items on the TSI that do not follow this general pattern.

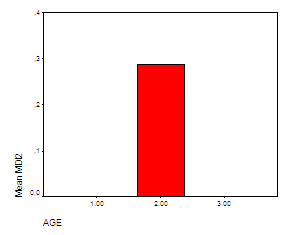

Interestingly, the bar graphs representing the significant items on the MDI also indicate similarities between the women in their 20’s and 40’s, while the women in their 30’s deviate in reference to the frequency of certain experiences. For example, in items 12, 18, 15, and 21 the frequency of these dissociative experiences was 0 for both the women in their 20’s and 40’s yet extremely high for the women in their 30’s. These experiences include, “feeling that there are more than one personality with different names within you, feeling that your hands and feet are not connected to your body, things around you suddenly appear strange or odd, feeling as if you are outside of your body, and suddenly things around you seem unreal.”

Graph 3: Graph representing the significant items on the MDI 12.

Graph 4: Graph representing the significant items on the MDI 18.

Graph 5: Graph representing the significant items on the MDI 15.

Graph 6: Graph representing the significant items on the MDI 21.

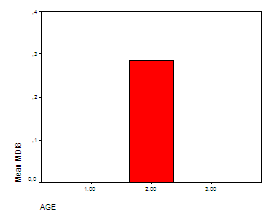

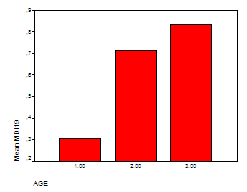

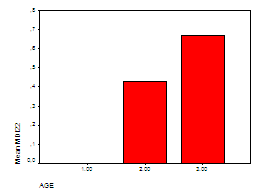

The only significant items that follow a steady increase in frequency of experience with the increase in age are items 19 (walking or driving without paying attention to where you are going) and 22 (feeling as if you are frozen inside and without feelings).

Graph 7: Graph representing the significant items on the MDI 19, a steady increase in frequency of experience with the increase in age.

Graph 8: Graph representing the significant items on the MDI 22, increase in frequency of experience with the increase in age.

Lastly, the significant items on the DAPS indicate that women in their 20’s have certain experiences least, while some experiences are lived out significantly more often by women in their 30’s (certain music causing fear ex. heavy metal) while other experiences significantly more often by women in their 40’s (obsessive-compulsive fear of being sexually abused or traumatized). In effect, the DAPS has captured something that both the TSI and the MDI have captured separately, as the TSI indicated that women in their 40’s had certain experiences the most, while the MDI concluded that it was women in their 30’s that had certain experiences the most. Hence it is the nature of these experiences that must be examined in order to yield insight. The women in their twenties did not show a significant amount of signs or symptoms of trauma. The women in their thirties showed the most dissociative symptoms and signs of trauma, while the women in their forties exhibited the most avoidance/anxious symptoms and signs of trauma.

4. Discussion

Each one of the questionnaires used in this study captures different type symptoms that are related to traumatic experiences. The TSI mostly regards avoidance/anxious symptoms and signs of trauma as it examines a person’s relationships with others, their relationships with themselves, their sexual life, symptoms of depression, anxiety, and self-appraisal. The MDI clearly looks to pinpoint dissociative symptoms, such as body dissociation, agnosia, multiple personalities, and distraction. Lastly, the DAPS mainly refers to certain addictive disorders, such as alcoholism, drug dependence, and suicidal thought. In addition, it also examines both avoidance/anxious and disscoistive signs and symptoms related to experiences of trauma.

Combining and comparing these three questionnaires we can infer that the older the woman, the more likely she is to have been traumatized or to be experiencing symptoms or signs of PTSD. Interestingly, it is the women in their thirties who experience the most dissociative symptoms, as indicated by the compelling results from the MDI. This can be explained as a reaction to a recent trauma experience, possibly expressed as Acute Stress Disorder (as indicated in the DSM-IV-TR), which occurs before the onset of PTSD. As indicated by Shalev et al. [8], dissociative symptoms (including depersonalization, derealization, amnesia, and out-of-body experiences) occur shortly after a traumatic experience and increase the probability of later developing PTSD. On the other hand, the women in their forties and up display more avoidance/anxious symptoms, indicative of PTSD, such as re-experiencing past unpleasant events and not being able get a grasp of themselves. For example, women in their forties and up responded most frequently to question #2 on the TSI “trying to forget about a bad time in your life” and question #4 on the TSI “Stopping yourself from thinking about the past”. These are the women who would display an exaggerated startle response (avoidance/anxious symptom) and who would not habituate to a re-occurring noise, as in the Shalev et al. study.

In effect, the results of our study can be used to infer that traumatic experiences faced by Greek females most likely occur during their thirties, thus causing acute and dissociative symptoms, which later subside as time passes, either disappearing fully or transforming into avoidance/anxious symptoms. In the months after an acute trauma, dissociative symptoms are common [12]. The dissociation tends to decrease over time [13]. Therefore, this is why women in their forties and up no longer display these intense dissociative symptoms as frequently as the women in their thirties, and rather have developed certain coping mechanisms and adaptations to make sense of their trauma that becme manifested in avoidance/anxious symptomatic behaviors and our experiences. The results of this study clearly follow the DSM-IV-TR descriptions of symptoms and course of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress disorder.

This is not to belittle these women’s experiences or to say that the traumatic experiences in their lives have ceased. Rather, perhaps the women have incorporated these symptoms into their daily lives and have developed psychological techniques and the strength to cope with ongoing trauma. Furthermore, the results clearly indicate that in Greece, the older a woman gets, the more likely she is to have experienced some form of trauma. Taking this study into consideration, and others like it, mental health professionals should try to create and implement prevention programs for the young women in Greece so that they may learn to cope and deal with dissociative symptoms, in effect decreasing the odds that they will develop diagnosable PTSD and the anxious/avoidance symptoms involved in this disorder.

We must also take into consideration the limitations of this study. Due to the use of self-report measures one can never be 100% sure that the participants’ responses are accurate and honest. More importantly, we must mention that in the past ten years, many natural disasters, such as earthquakes, floods, and fires have occurred in Greece, as well as many wars in countries very close in proximity to Greece. Along with the economic instability, these traumatic events may have contributed to or served as confounds to the results of this study. The older women had seen more wars, fires, poverty, and have lived through more earthquakes than their younger counterparts. Perhaps the results of this study have illustrated the psychological effects of many years of hardship, war, and natural disaster. Additional studies must be conducted with a larger sample size and possibly with methods that may control for the aforementioned confounds. Furthermore, it is imperative that mental health professionals and researchers continue to investigate the potential risk factors for PTSD so that we can promptly and efficiently deal with the consistently rising prevalence of the disorder and the survivors of these traumas.

References

- Fairbank JA, Brown TA. Current behavioral approaches to the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. The Behavior Therapist 3 (1987): 57-64.

- Keane TM, Zimmering RT, Caddell J. A behavioral formulation of posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnamese veterans. The Behavior Therapist 8 (1985): 9-12.

- Foy DW, Resnick, HS, Carroll EM, et al. Behavior therapy. In A.S. Bellack & M. Hersen (Eds.), Handbook of comparative treatments for adult disorders (1990): 302-315.

- Chemtob C, Roitblat HC, Hamada RS, et al. A cognitive action theory of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2 (1988): 253-257.

- Foa EB, Kozak MG. Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin 99 (1986): 20-35.

- Horowitz MJ. Psychotherapy. In A.S. Bellack & M. Hersen (Eds.), Handbook of comparative treatments for adult disorders (1990): 289-301).

- van der Kolk BA, Dreyfus D, Michaels M, et al. Fluoxetine in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 15 (1994): 517-523.

- Shalev AY, Peri T, Canetti L, et al. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder in injured trauma survivors: A prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry 153 (1996): 219-225.

- Pilowsky I. Cryptotrauma and ‘accident neurosis’. British Journal of Psychiatry 147 (1985): 310-312.

- Mowder BA, Gutman M, Sossin MK, et al. Trauma and parenting: Effects of 9/11 on parents’ role perceptions and behaviors. APA Conference 2004. Honolulu (2004).

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski D, et al. Traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder in an urban population. Archives of General Psychiatry 48 (1991): 216-222.

- Sargant WW, Slater E. Acute war neuroses. Lancet 2 (1940): 1-2.

- Davidson JRT, Foa EB. Diagnostic issues in posttraumatic stress disorder: Considerations for the DSM-IV. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 100 (1991): 346-355.