A Preventive Approach to Inpatient Suicides. A Recommendation for Practice Based On Clinical Data from the Czech Republic

Article Information

Adam ?aludek*, David Marx

Division of Public Health, Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles university, Czech Republic

*Corresponding Author: Adam Zaludek, Division of Public Health, Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles university, Czech Republic

Received: 15 March 2019; Accepted: 27 March 2019; Published: 03 April 2019

Citation: Adam Zaludek, David Marx. A Preventive Approach to Inpatient Suicides. A Recommendation for Practice Based On Clinical Data from the Czech Republic. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Disorders 3 (2019): 057-066.

Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Inpatient suicide is a severe event that carries a great emotional charge. Not all of suicidal attempts are predictable, but they are often preventable. When there is no precise method of prediction of suicidal behaviour, hospital management has to ensure a safe clinical environment and clinitians have to be able to recognize patient that is at risk of suicide. The aim of this article is to recommend how to reduce the risk of inpatient suicide, according to the recent data from the Czech republic.

Methods: In our study, we have sent questionnaires to acute psychiatric departments in the Czech republic. Questionnaires were designed to cover the area of clinical environment, patient assessment and the use of risk management tools according to the suicide risk reduction.

Results: The study found out that there are problems with the whole process of inpatient suicide prevention. There is no standardised scale of suicide risk assessment in hospitals involved in the study. Psychiatric wards are old and in a bad technical state, so the clinical environment is unsafe. There are also problems in using pro- and retroactive risk management tools, such as failure mode and effect analysis and root cause analysis.

Conclusion: Inpatients suicides are very severe adverse events. According to our study, it is necessary to standardize the way of suicide risk assessment and ensure a safe clinical environment for those patients at the risk of suicide, keeping in mind to balance the necessary restrictions and the dignity of patients.

Keywords

Prevention, Inpatient suicide, Risk management, Quality management

Prevention articles Prevention Research articles Prevention review articles Prevention PubMed articles Prevention PubMed Central articles Prevention 2023 articles Prevention 2024 articles Prevention Scopus articles Prevention impact factor journals Prevention Scopus journals Prevention PubMed journals Prevention medical journals Prevention free journals Prevention best journals Prevention top journals Prevention free medical journals Prevention famous journals Prevention Google Scholar indexed journals Inpatient suicide articles Inpatient suicide Research articles Inpatient suicide review articles Inpatient suicide PubMed articles Inpatient suicide PubMed Central articles Inpatient suicide 2023 articles Inpatient suicide 2024 articles Inpatient suicide Scopus articles Inpatient suicide impact factor journals Inpatient suicide Scopus journals Inpatient suicide PubMed journals Inpatient suicide medical journals Inpatient suicide free journals Inpatient suicide best journals Inpatient suicide top journals Inpatient suicide free medical journals Inpatient suicide famous journals Inpatient suicide Google Scholar indexed journals Risk management articles Risk management Research articles Risk management review articles Risk management PubMed articles Risk management PubMed Central articles Risk management 2023 articles Risk management 2024 articles Risk management Scopus articles Risk management impact factor journals Risk management Scopus journals Risk management PubMed journals Risk management medical journals Risk management free journals Risk management best journals Risk management top journals Risk management free medical journals Risk management famous journals Risk management Google Scholar indexed journals Quality management articles Quality management Research articles Quality management review articles Quality management PubMed articles Quality management PubMed Central articles Quality management 2023 articles Quality management 2024 articles Quality management Scopus articles Quality management impact factor journals Quality management Scopus journals Quality management PubMed journals Quality management medical journals Quality management free journals Quality management best journals Quality management top journals Quality management free medical journals Quality management famous journals Quality management Google Scholar indexed journals suicidal behaviour articles suicidal behaviour Research articles suicidal behaviour review articles suicidal behaviour PubMed articles suicidal behaviour PubMed Central articles suicidal behaviour 2023 articles suicidal behaviour 2024 articles suicidal behaviour Scopus articles suicidal behaviour impact factor journals suicidal behaviour Scopus journals suicidal behaviour PubMed journals suicidal behaviour medical journals suicidal behaviour free journals suicidal behaviour best journals suicidal behaviour top journals suicidal behaviour free medical journals suicidal behaviour famous journals suicidal behaviour Google Scholar indexed journals psychiatric care articles psychiatric care Research articles psychiatric care review articles psychiatric care PubMed articles psychiatric care PubMed Central articles psychiatric care 2023 articles psychiatric care 2024 articles psychiatric care Scopus articles psychiatric care impact factor journals psychiatric care Scopus journals psychiatric care PubMed journals psychiatric care medical journals psychiatric care free journals psychiatric care best journals psychiatric care top journals psychiatric care free medical journals psychiatric care famous journals psychiatric care Google Scholar indexed journals pharmacoresistance articles pharmacoresistance Research articles pharmacoresistance review articles pharmacoresistance PubMed articles pharmacoresistance PubMed Central articles pharmacoresistance 2023 articles pharmacoresistance 2024 articles pharmacoresistance Scopus articles pharmacoresistance impact factor journals pharmacoresistance Scopus journals pharmacoresistance PubMed journals pharmacoresistance medical journals pharmacoresistance free journals pharmacoresistance best journals pharmacoresistance top journals pharmacoresistance free medical journals pharmacoresistance famous journals pharmacoresistance Google Scholar indexed journals personality disorder articles personality disorder Research articles personality disorder review articles personality disorder PubMed articles personality disorder PubMed Central articles personality disorder 2023 articles personality disorder 2024 articles personality disorder Scopus articles personality disorder impact factor journals personality disorder Scopus journals personality disorder PubMed journals personality disorder medical journals personality disorder free journals personality disorder best journals personality disorder top journals personality disorder free medical journals personality disorder famous journals personality disorder Google Scholar indexed journals schizophrenia articles schizophrenia Research articles schizophrenia review articles schizophrenia PubMed articles schizophrenia PubMed Central articles schizophrenia 2023 articles schizophrenia 2024 articles schizophrenia Scopus articles schizophrenia impact factor journals schizophrenia Scopus journals schizophrenia PubMed journals schizophrenia medical journals schizophrenia free journals schizophrenia best journals schizophrenia top journals schizophrenia free medical journals schizophrenia famous journals schizophrenia Google Scholar indexed journals depression articles depression Research articles depression review articles depression PubMed articles depression PubMed Central articles depression 2023 articles depression 2024 articles depression Scopus articles depression impact factor journals depression Scopus journals depression PubMed journals depression medical journals depression free journals depression best journals depression top journals depression free medical journals depression famous journals depression Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

1. Introduction

An inpatient suicide is a severe event that carries a great emotional charge [1]. The definition of inpatient suicide is: any suicide of a patient during hospitalisation, inside or outside the hospital, e.g. when taking a walk, on during permitted life of hospital for a certain period of time or during treatment in another hospital while still receiving psychiatric care [2]. In the Czech Republic, the frequency of such events was 0.0024 per 1.000 patients in 2014 [3]. The world prevalence of inpatient suicides is 0.1 – 0.4% [1]. In spite of the fact, that nearly 40% of suicide victims are in touch with psychiatric care during the last year of their lives [4], it is still very difficult for health care professionals to predict suicidal activity [5], and risk factors among the general population and inpatients are different [6]. The number of inpatient suicide is the highest during the first week after hospital admission and the next 72 hours following discharge from the hospital [7]. Risk factors among inpatients are: previous suicide attempt, pharmacoresistance and severe side effects of medication, physical assault in medical history, personality disorder, schizophrenia, depression, female sex and a short length of stay [8]. Another problem is that behavioural health care professionals are rather focused on aspects of patients‘ behaviour such as an aggression, damage of furniture or other equipment and self-harm than the complex clinical assessment and exploring risk factors [9]. The main methods of inpatient suicides are: hanging, suffocation (for example: using a plastic bag from a trash can), laceration, jumping from height place and overdosing [1].

2. The Preventive Approach – Suicide Risk Assessment

A complex suicide risk assessment is still a very difficult task. Even if there are plenty of suicide risk screening tools, none of them is considered to be a golden standard, a tool that can predict future suicidal activity with high sensitivity and specifity. Not all of the suicide attempts are predictable, but they are preventable. A suicide is considered to be a failure of proactive tools of a risk management and a proof of unsafe clinical environment [10]. Maintaining a safe environment in hospitals as a crucial suicide prevention factor is rarely the topic of discussion among health care professionals [11]. Because there is no gold standard, that could precisely predict the risk of suicide of a patient (as, for example, a Glasgow coma scale evaluating the level of consciousness), health care professionals try to compensate this insufficiency by more strict and frequent observations of a patient. This includes observation of patients by hospital workers or CCTV observation [12].

On the other hand, there are clinical studies pointing out that observation of patients is not a sufficient preventive approach [13]. There are cases of patients, who were able to take their own lives, while being continuously observed by the staff of a psychiatric ward [14]. A recommended procedure is to look for suicidal behaviour in the a medical history of patients and their families. All patients admitted to a psychiatric unit or department should be checked for the presence of suicidal thoughts by using a short, evidence-based screening tool. This could be, for example, the SAD PERSONS scale or the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). According to studies, a positive screening in PHQ-9 is associated with 10 times higher suicide probability [15]. Suicide risk should be reevaluated every time a patient is discharged from the hospital or leaves the ward [16]. On the other hand, screening tools are not without flaws. In spite of the fact that suicidal thoughts, that are the topic of the screening tools, are a serious risk factor, almost 78% of patients could deny their existence before a suicide attempt [1].

Patients that are at risk of committing suicide should be hospitalized in a safe environment. The staff should check them and also their families and friends for dangerous objects, for example, for: knives, belts, plastic bags and other things that can be used by patients to hurt themselves. Patients should be treated for their psychiatric disorders and suicidality as well, which means pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy and ongoing care after the discharge. It is also important to cooperate with their families and close friends to create synergy and supportive network. To promote such preventive steps, it is crucial to educate health care professionals, so they know how to explore suicidal ideations and how to communicate with patients at risk of suicide. It is recommended to implement a standardized process of suicide risk assessment, as well as the process of care for patients at risk of suicide. The whole process of suicide prevention demands a full complementation of a patient’s medical record and the risk of suicide needs to be pointed out. Such information cannot be lost, when such patient is sent to another health facility or to another doctor or when another staff starts to take care of the patient.

3. A Safe Environment in the Psychiatric Ward

Unsafe environment is considered to be one of the most frequent root causes of completed suicides [1]. One of the risks is an absence of a ligature resistant environment, that is defined as “Without points where a cord, rope, bed sheet, or other fabric/material can be looped or tied to create a sustainable point of attachment that may result in self-harm or loss of life.”[16].

Another risks are unbreakable handles, faucets, shower heads, plastic bags in trash containers and everywhere else, belts, shoelaces, tiles, that could be used as sharp objects and others [16-18].

4. The Current State of Psychiatric Care in the Czech Republic

There is an ongoing reform of psychiatric care in the Czech Republic, and it’s main aim is to reduce the number of beds in psychiatric hospitals. After the reduction in 2016 the total capacity of patients in psychiatric hospitals was 8741beds and 1298 beds in psychiatric departments. The reduction should be balanced by creating a community based centers of mental health and community teams of behavioral health specialists [19]. The actual level of staffing in mental health services is insufficient. There were 523,71 physicians in psychiatric hospitals in 2016. This means that 1 physician is responsible for the care of 16.7 patients. According to OECD, there are 14 psychiatrists to 100.000 inhabitants. In comparison, there are 62 general practitioners to 100.000 inhabitants. The European ratio is 15 psychiatrists to 100.000 inhabitants [23].

Mental and behavioural health care is underfinanced in the Czech Republic, as there is spent only 0.26% of Gross domestic product (GDP), in comparison with the European Union, where the spending is about 2% of GDP, the average spending of each country in the European Union is 5 – 10% 19, 20]. This affects also material and technical equipment. Psychiatric hospitals, where the greatest part of patient care takes place, are old. The other problem is insufficient staffing [1].

5. The Actual Research of Current Suicide Prevention in Psychiatric Hospitals and Departments

5.1 MethodsA study of inpatient suicides at acute psychiatric wards and departments took place in the Czech Republic in 2017. The aim of this study was to provide information about the current preventive approach towards inpatient suicides. The questionnaires were created according to proactive risk management tools mentioned in this article (suicide risk assessment, safety environment etc.). Those questionnaires were focused on equipment of psychiatric wards and departments, risk assessment, approach of health care professionals, checks of patients and their families and friends for contraband. Hospitals‘ standards of care were also checked, whether there are standardised procedures of risk assessment, competencies of staff, whether the management uses risk management tools. Questionnaires were addressed to the directors of psychiatric hospitals and wards and health care quality managers. Data that were provided had been anonymized.

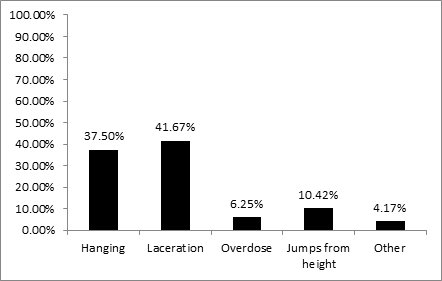

5.2 ResultsData covered the area of 377 acute psychiatric beds (out of approximately 3.000 in total). In the years 2011 – 2016 there were 11 completed suicides reported, and there were 48 suicide attempts in psychiatric hospitals and departments in this time period. In 2 hospitals involved in the study there were more than 2 completed suicides. The main methods of suicides are displayed on the Graph 1 [22].

Graph 1: Methods of inpatient suicides in the Czech Republic 2011 – 2016 [22].

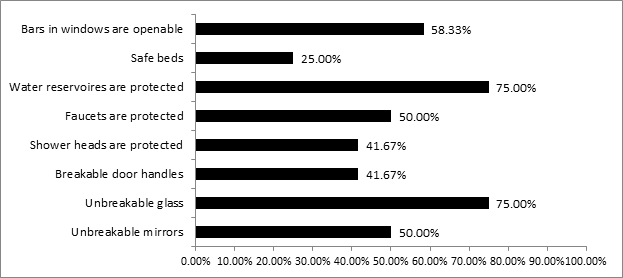

The lack of safe environment is not surprising keeping in mind the underfinancing of psychiatric care in the Czech Republic. In spite of the most frequent method of suicide attempt – hanging – there are still insufficient number of hospitals using equipment and furniture preventing such way of suicide. Less than half of hospitals uses: breakable shower heads, breakable door handles or knobs that allow a slip of a loop. A quarter of hospitals have ligature resistant beds for patients, such beds do not allow patients to attach a loop. The situation is displayed on the Graph 2 [22].

Graph 2: Clinical environment at acute psychiatric wards in the Czech Republic [22].

The most frequent method of suicide in the hospitals involved in the study was lacaretion (despite the trend in the general population). Therefore, it is important to eliminate tiles on floors and walls, because they can be broken and used as a sharp object. Less than 17% of the hospitals involved in the study provide an environment regarding this risk.

5.4 Suicide risk assessment and preventionSuicide risk assessment was performed by nurses in 71,43% of acute psychiatric hospitals and departments involved in the study. Only 57, 14% of hospitals consider suicide risk assessment as the duty of psychiatrists. On the other hand, 85,71% of hospitals involved in the study have a standardised scale that is used as a risk assessment tool. A serious problem is the re-evaluation of this risk. 85, 71% of hospitals have a standardized procedure of evaluating the risk during the admission to the hospital, but in other critical periods (before discharge, before leaving the ward or before a transfer to another ward) it is re-evaluated insufficiently.

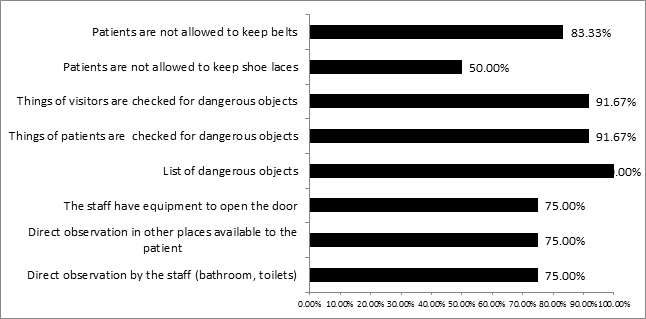

All the acute psychiatric hospitals and units involved in the study have a list of hazardous items (knives, forks, lighters etc.), that are prohibited to be brought to hospital, and health care professionals are skilled in checking patients and their visitors for such items. Belts are prohibited commonly, but only half of the hospitals also prohibits shoe laces, in spite of the fact that they are hazardous as well. See the graph 3 [22].

Graph 3: Suicide prevention – the action of the staff [22].

According to a risk management, it is not an appropriate approach. Patients who would want to hang themselves do not have to make a big effort to do it. They do not have to be above the ground neither. They simply can put a loop over their necks and to lean forward [17]. That is a reason, why shoe laces are very hazardous item.

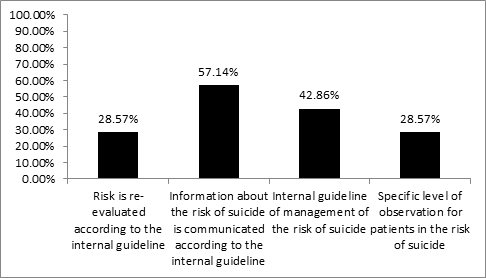

5.5 An approach to hospital managementA standardisation of health care processes is a very important risk management tool, as it is evidence-based and so it decreases variability in outcomes of care for the patient [21]. Health care management is responsible for standardisation of processes and management standards of care for patients who are at risk of suicides. One of the most important steps in inpatient suicide prevention is a suicide risk assessment, communication of this risk, re-evaluation of the risk - the level of observation and maintaining a safe environment for patients at the risk of suicide. The actual situation in the Czech Republic is displayed on the graph 4 [22].

Graph 4: The hospital risk management strategy [22].

Only 57, 14% of acute psychiatric hospitals and wards have a standard that focuses on suicide risk assessment, 28, 57% have a standard of how often and how to re-evaluate the risk. The exact same number of hospitals has a standard for the level of observation for patients at the risk of suicide. 42,86% of hospitals have a standard for management of care for patients at the risk of suicide. Hospitals involved in the study use a retroactive management tool – the Root cause analysis – in 85,71%.

5.6 DiscussionThe actual preventive approach of inpatient suicide at acute psychiatric wards and hospitals is unsatisfying. Acute psychiatric hospitals and wards, where the greatest part of acute psychiatric care takes place, are in a bad technical state and the building of new wards and units is rare. The staffing levels do not fulfil even the recommendation of the Ministry of Health. Psychiatric care is underfinanced and stigmatized. The situation is far more complicated by the novelization of the Act on Criminal Liability of Legal Persons and Procedure against them. This novelization has completely changed the responsibility for maintaning a safe environment in hospitals. Hospitals are now obliged by the law to use compliance programmes for maintaining a safe environment, other wise they can be sued for a great amount of money [23].

From this point of view the insufficient approach of psychiatric hospitals and wards towards the inpatient suicide is far more alarming. It is strongly recommended to create a standardised procedure of care for the patients at a risk of suicide, from the risk assessment to a safe discharge from the hospital. All patients admitted to psychiatric wards should be examined by a psychiatrist and a standardised scale of risk assessment should be used as well to increase the level of objectivity. There are a lot of scales of suicide risk assessment [10], regarding the insufficient staffing level, it is better to choose the scale that do not require a lot of time to administrate and that can be used throughout the hospital. Using different risk evaluation tools on various departments is a risk as it can bring different outcomes.

The form of suicide risk communication and documentation should be standardised as well, and patients should be hospitalised in a safe environment with an appropriate level of observation.

All the areas that could be accessed by patients should be ligature free – shower heads, door handles, faucets should be breakable to prevent attachement of a loop. Hooks, door knobs, radiators and pipes should be avoided or placed high, so that patients cannot not reach them. Breakable door handles should be weight-tested. Beds for patients at the risk of suicide should be also ligature resistant. The furniture should be light and unbreakable. For maintaining a safe environment, it is also very important to prevent access of patients to sharp object (knives, shards, tiles). Mirrors should be either unbreakable or made of plastic foil. Polished metals are not recommended because they can be bent and their sharp edge could be used as a knife. For reducing the risk of suicide it is a very useful step to check patients and their visitors for sharp objects. Knives, shoe laces, belts, but also plastic bags or headphones should be prohibited.

In the case of patient’s suicide attempt, it is also very important that health care professionals have all the tools necessary for opening doors of patients‘ rooms. Doors should be opened into a corridor rather than into a room, this way patients cannot block themselves inside. A part of a complex suicide prevention process is a treatment of psychiatric disorder and the involvement of family and close friends in a patient’s plan of care. As the patient‘s psychiatric disorder is treated, it is necessary to re-evaluate the risk of suicide as an indicator of care, and patients should be always re-evaluated for the risk of suicide before discharge, before leaving the ward and before their transfer to the next ward. Patients should be asked whether they have suicidal thoughts every day and every time they speak with a psychiatrist. Despite the ongoing reform of psychiatric care in the Czech Republic, there is still no guideline how for creating and maintaining a safe environment for psychiatric inpatients, but there are such manuals abroad [18].

5.7 ConclusionPsychiatric inpatients very often behave in a way that is dangerous to them and/or to others. Not all suicide attempts are predictable, but they are preventable. Therefore, it is necessary to make an effort toward maintaining a safe environment. We cannot manage anything, if we do not measure the risk, use the appropriate tools, that help us to find out, which patients are at a risk of suicide. Patients do not speak about suicidal thoughts frequently, so we should ask them actively and use standardised suicide risk assessment tools. Even if maintaining a safe environment means eliminating of hazardous things and equipment and more strict ways of observation of patients, it is important to remember, that patients are living beings with feelings and emotions. Health care professionals should therefore keep balance in restrictions and dignity of patients.

Fundings

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Conflict of Interest

None declared

Key Points- The article is focused on an inpatient suicide risk reduction strategy as a part of quality management based on actual clinical data.

- The article presents a complex process of inpatient suicide risk reduction process that could be used also in other specialisations than mental health services. The process covers areas of patients‘ environment, suicide risk assessment, use of risk and quality management tools etc.

- Mental disorders present a greater burden of disease from the perspective of public health, so the inpatient suicide risk reduction strategy is an important part of maintaining of public health as a fundamental right of all individuals.

References

- Combs H, Romm S. Psychiatric inpatient suicide: a literature review. Primary psychiatry 14 (2007): 67-74.

- Oehmichen M, Staak M. Suicide in the psychiatric hospital. International trends and medico legal aspects. Acta Med Leg Soc (Liege) 38 (1988): 215-223.

- Inpatient suicide amongst patients with a psychiatric disorder. (or nearest year), in Quality and outcomes of care, OECD Publishing, Paris (2014).

- Appleby L, et al. Suicide within 12 months of contact with mental health services: national clinical survey. BMJ 318 (1999):1235-1239.

- Hanra S, Mahintamani T, Bose S, et al. Inpatient Suicide in a Psychiatric Hospital: A Nested Case–control Study. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 38 (2016): 571-576.

- Bowers L, Banda T, Nijman H. Suicide inside: A systematic review of inpatient suicides. J Nerv Ment Dis 198 (2010): 315-328.

- Quin P, Nordentoft M. Suicide risk in relation to psychiatric hospitalization: an evidence based on longitudinal registers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62 (2005): 427-432.

- Neuner T, Schmid R, Wolfersdorf M, et al. Predicting inpatient suicides and suicide attempts by using clinical routine data? Gen Hosp Psychiatry 30 (2008): 324-330.

- Bowers L, Allan T, Simpson A, et al. Identifying key factors associated with aggression on acute inpatient psychiatric wards. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 30 (2009): 260-271.

- Ghasemi P, Shaghaghi A, Allahverdipour H. Measurement scales of suicidal ideation and attitudes: a systematic review article. Health promotion perspectives 5 (2015):156-168.

- Kanerva A, Lammintakanen J, Kivinen T. Nursing staff’s perceptions of patient safety in psychiatric inpatient Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 52 (2016): 25-31.

- Slemon A, Jenkins E, Bungay V. Safety in psychiatric inpatient care: The impact of risk management culture on mental health nursing practice. Nurs Inq 24 (2017): e12199.

- Muralidharan S, Fenton M. Containment strategies for people with serious mental illness. The Cochrane Library 2 (2012): 1-15.

- Sakinofsky I. Preventing suicide among inpatients. The Canadian journal of psychiatry 59 (2014): 131-140.

- Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, et al. Dose response on the PHQ-9 Depression Questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death?. Psychiatr Serv 64 (2013): 1195-1202.

- Joint Commission International. Suicide Prevention in Health Care Settings. The Joint Commission Perspectives 38 (2018): 1-14.

- Joint commission. A follow -up report on preventive suicide: focus on medicie/surgical units and the emergency department. Sentinel event alert 17 (46): 1-4.

- Sine DI, Hunt JM. Behavioral Health Design Guide. Behavioral Health Facility Consulting, LC (2018).

- Petr W. Reforma systému psychiatrické pé?e: mezinárodní politika, zkušenost a doporu?ení. Praha: Psychiatrické centrum Praha (2013).

- Raboch J, Weningová B. Mapování stavu psychiatrické pé?e a jejího sm??ování v souladu se strategickými dokumenty ?eské republiky (a zahrani?í). Odborná zpráva z projektu. Praha: ?eská psychiatrická spole?nost (2012).

- Byers JF, White SV. Patient safety: Principles and Practice. Springer publishing company (2004).

- ?aludek, A. Sebevra?edné jednání hospitalizovaných pacient? no ?eských psychiatrických l??kových odd?leních „Psychiatric inpatien suicide in the Czech Republic“. Psychiatr. Praxi 19 (2018): 69-75.

- Act on Criminal Liability of Legal Persons and Procedure against them. Parlament ?eské republiky (2016).