Effect of Behavior Change Communication through the Health Development Army on Dietary Practice of Pregnant Women in Ambo District, Ethiopia: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Community Trial

Article Information

Mitsiwat Abebe Gebremichael1*, Tefera Belachew Lema2

1Public health department, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ambo University, Ambo, Ethiopia

2Population and family health Department, Human nutrition unit, College of Public Health and Medical Sciences, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia

*Corresponding Author: Mitsiwat Abebe Gebremichael, Public health department, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ambo University, Ambo, Ethiopia

Received: 05 September 2022; Accepted: 12 September 2022; Published: xx September 2022

Citation: Mitsiwat Abebe Gebremichael, Tefera Belachew Lema. Effect of Behavior Change Communication through the Health Development Army on Dietary Practice of Pregnant Women in Ambo District, Ethiopia: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Community Trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology Research 5 (2022): 225-237.

Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Given how important pregnancy is to a woman's life, both the mother's and the unborn child's health and wellbeing are greatly influenced by the mother's dietary habits during and throughout pregnancy. Therefore, the objective of the study was to investigate the effect of behavior change communication (BCC) through the health development armies on the dietary practices of pregnant women.

Methods: A two-arm parallel cluster randomized controlled community trial with baseline and endline measurements using quantitative data collection methods was conducted in Ambo district among 770 pregnant women (385 in control and 385 in intervention groups). Endpoint data from 372 intervention and 372 control groups were gathered, respectively. In the intervention group, health development armies delivered the BCC main message based on intervention protocol. The intervention began in July 2018, and data collection for the endline began in October, 2018. The control group received the standard care provided by the healthcare system during an ANC visit. The study of effect measure was done using a log-binomial model to estimate the adjusted relative risk and its 95% confidence interval (CI) of the risk factors for suboptimal dietary practice.

Result: At the end of the study, the overall optimal dietary practice among the intervention group was 65.1%, while among the control group it was 34.9% (p< 0.001). Pregnant women who received intervention were 41.0% less likely to be at risk of being suboptimal in dietary practice compared to pregnant women who were in the control group (ARR = 0.591, 95%CI: 0.510-0.686).

Conclusions: This study revealed that behavior change communication (BCC) through the health development armies is effective in improving the dietary practices of pregnant women. As a result, BCC through the Health Development Army is recommended t

Keywords

Dietary practice; Behavior change communication; Pregnant women; Health development army

Dietary practice articles Dietary practice Research articles Dietary practice review articles Dietary practice PubMed articles Dietary practice PubMed Central articles Dietary practice 2023 articles Dietary practice 2024 articles Dietary practice Scopus articles Dietary practice impact factor journals Dietary practice Scopus journals Dietary practice PubMed journals Dietary practice medical journals Dietary practice free journals Dietary practice best journals Dietary practice top journals Dietary practice free medical journals Dietary practice famous journals Dietary practice Google Scholar indexed journals Behavior change communication articles Behavior change communication Research articles Behavior change communication review articles Behavior change communication PubMed articles Behavior change communication PubMed Central articles Behavior change communication 2023 articles Behavior change communication 2024 articles Behavior change communication Scopus articles Behavior change communication impact factor journals Behavior change communication Scopus journals Behavior change communication PubMed journals Behavior change communication medical journals Behavior change communication free journals Behavior change communication best journals Behavior change communication top journals Behavior change communication free medical journals Behavior change communication famous journals Behavior change communication Google Scholar indexed journals Pregnant women articles Pregnant women Research articles Pregnant women review articles Pregnant women PubMed articles Pregnant women PubMed Central articles Pregnant women 2023 articles Pregnant women 2024 articles Pregnant women Scopus articles Pregnant women impact factor journals Pregnant women Scopus journals Pregnant women PubMed journals Pregnant women medical journals Pregnant women free journals Pregnant women best journals Pregnant women top journals Pregnant women free medical journals Pregnant women famous journals Pregnant women Google Scholar indexed journals Health development army articles Health development army Research articles Health development army review articles Health development army PubMed articles Health development army PubMed Central articles Health development army 2023 articles Health development army 2024 articles Health development army Scopus articles Health development army impact factor journals Health development army Scopus journals Health development army PubMed journals Health development army medical journals Health development army free journals Health development army best journals Health development army top journals Health development army free medical journals Health development army famous journals Health development army Google Scholar indexed journals Nutrition articles Nutrition Research articles Nutrition review articles Nutrition PubMed articles Nutrition PubMed Central articles Nutrition 2023 articles Nutrition 2024 articles Nutrition Scopus articles Nutrition impact factor journals Nutrition Scopus journals Nutrition PubMed journals Nutrition medical journals Nutrition free journals Nutrition best journals Nutrition top journals Nutrition free medical journals Nutrition famous journals Nutrition Google Scholar indexed journals pregnancy articles pregnancy Research articles pregnancy review articles pregnancy PubMed articles pregnancy PubMed Central articles pregnancy 2023 articles pregnancy 2024 articles pregnancy Scopus articles pregnancy impact factor journals pregnancy Scopus journals pregnancy PubMed journals pregnancy medical journals pregnancy free journals pregnancy best journals pregnancy top journals pregnancy free medical journals pregnancy famous journals pregnancy Google Scholar indexed journals Medicine articles Medicine Research articles Medicine review articles Medicine PubMed articles Medicine PubMed Central articles Medicine 2023 articles Medicine 2024 articles Medicine Scopus articles Medicine impact factor journals Medicine Scopus journals Medicine PubMed journals Medicine medical journals Medicine free journals Medicine best journals Medicine top journals Medicine free medical journals Medicine famous journals Medicine Google Scholar indexed journals Health Sciences articles Health Sciences Research articles Health Sciences review articles Health Sciences PubMed articles Health Sciences PubMed Central articles Health Sciences 2023 articles Health Sciences 2024 articles Health Sciences Scopus articles Health Sciences impact factor journals Health Sciences Scopus journals Health Sciences PubMed journals Health Sciences medical journals Health Sciences free journals Health Sciences best journals Health Sciences top journals Health Sciences free medical journals Health Sciences famous journals Health Sciences Google Scholar indexed journals Got’s articles Got’s Research articles Got’s review articles Got’s PubMed articles Got’s PubMed Central articles Got’s 2023 articles Got’s 2024 articles Got’s Scopus articles Got’s impact factor journals Got’s Scopus journals Got’s PubMed journals Got’s medical journals Got’s free journals Got’s best journals Got’s top journals Got’s free medical journals Got’s famous journals Got’s Google Scholar indexed journals HIV/AIDS articles HIV/AIDS Research articles HIV/AIDS review articles HIV/AIDS PubMed articles HIV/AIDS PubMed Central articles HIV/AIDS 2023 articles HIV/AIDS 2024 articles HIV/AIDS Scopus articles HIV/AIDS impact factor journals HIV/AIDS Scopus journals HIV/AIDS PubMed journals HIV/AIDS medical journals HIV/AIDS free journals HIV/AIDS best journals HIV/AIDS top journals HIV/AIDS free medical journals HIV/AIDS famous journals HIV/AIDS Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

Trial registration number:

PACTR201805003366358

Background

Nutrition throughout life has a major effect on health. A mother's dietary practices at conception and throughout pregnancy play a key role in determining her health and well-being as well as that of her child [1]. The recommended intake for most nutrients is increased during pregnancy, but the majority of pregnant women have inadequate nutrient intake when compared to the recommended standards by the World Health Organization (WHO) [2,3]. Thus, pregnant women should eat diversified foodstuffs that contain an adequate amount of energy, protein, vitamins, minerals, and water [4]. According to Essential Nutrition Actions (ENA) framework, optimal dietary practice of pregnant women encompasses quantity (increased in portion size and frequency of diet) and quality of diet (diversified food containing fruit, vegetables and animal origins [5,6]. Behavior change communication (BCC) is widely recognized as one of the main health promotion strategies. It is an interactive process of working with individuals and communities to develop communication strategies to promote positive behaviors as well as create a supportive environment to enable them to adopt and sustain positive behaviors [7,8]. According to the literature, the magnitude of dietary practices of pregnant women varies within the country. According to the institution-based study done in Mettu Karl Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia, the prevalence of sub-optimal dietary practices among pregnant women was 22% [9]. According to the study done in Gedeo zone, southern Ethiopia, in 2018, around one-third (67.8%) of pregnant women had poor dietary practices [10]. Similarly, 73.1% of pregnant women showed poor dietary practice in the Ambo district, Ethiopia [11]. Poor dietary practice, which results in undernutrition, is a major public health concern for women of reproductive age, particularly pregnant women, because it has a negative impact on pregnancy outcomes [12]. Malnourished pregnant women can have a variety of problems. It puts women at risk for miscarriage, intrauterine growth retardation, low birth weight, and infant morbidity and mortality, among other things [13]. Different researchers show socio-demographic factors like age, wealth index, residence, household food security, family size, illiteracy or low education, availability, and accessibility of nutritious food are common factors affecting maternal dietary practice. Similarly, maternal and health service-related factors like years at marriage, ANC visits, level of knowledge, awareness, and attitude, practices regarding nutritious foods, and women’s decision-making status all have an impact on the dietary practices of pregnant women [14-18]. Behavior change communication interventions were effective in improving dietary practice in pregnant women [19,20]. A study done among pregnant women in Indonesia revealed that providing nutrition education through small groups with interactive methods improves the nutritional habits of pregnant women [21]. Similarly, one study done in Ethiopia showed the positive significant effect of BCC intervention to promote consumption of a healthy diet during pregnancy [22]. However, in Ethiopia, the routine nutrition education given by the health system is "vague and inconsistent." Professionals have been advising pregnant women to eat one additional meal from available foodstuffs [23]. As a result, the dietary practices of pregnant women are poor, and maternal undernutrition remains a major public health problem in the country [24]. Therefore, behavior change communication is integral to improving the dietary practices of pregnant women [25]. Health Development Armies (HDAs) are volunteers, have significant potential to improve access to Primary Health Care (PHC) in Ethiopia, and support the work of the Health Extension Workers (HEWs) [26] and there is an impressive improvement in maternal and child health and service use after the introduction of HDAs in the country [27-30]. However, to the best of the researcher’s knowledge, no evidence was found on BCC interventions delivered through HDAs to improve the dietary practices of pregnant women. This paper aims to apply the HDAs as a pivotal role implementer in improving the dietary practices of pregnant women. To the best of our knowledge, no research has been done on the effect of BCC through the health development army on dietary practices among pregnant women. Thus, this study was aimed to investigate the effect of BCC through the health development army on dietary practices among pregnant women in the study area.

Research Hypothesis

H0: Behavior change communication through the health development army has no effect on the dietary practices of pregnant women.

H1: Behavior change communication through the health development army has a positive effect on the dietary practices of pregnant women.

Methods and Materials

Study design, study period and setting

A two-arm parallel cluster randomized controlled community trial (CRCCT) with baseline and end-line measurement was conducted from June 2018 to November 2018 among pregnant women in the Ambo district of West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia. The Ambo district is located in the western part of Ethiopia, 114 km from Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. Based on 2017 district health office data, it has 37,454 and 6976 reproductive age group and pregnant women, respectively [31]. Maize, wheat, teff, barley, and sorghum are the common cereals cultivated in the zone [32].

Sample size determination and study population

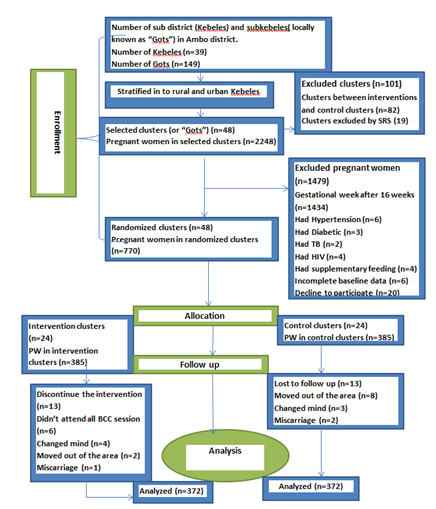

The sample size was calculated using the G Power 3.1.9.2 program with a power of 80% for Fisher’s exact test and a precision of 5% alpha level. According to Fekadu et al. (2016), the proportion of optimal dietary practice among non-exposed pregnant women (p1) 0.34 was used [33], effect size (h) of 0.3, and with the allocation ratio of intervention to control group (N2/N1) of 1, proportion (p2) 0.65 was obtained. The calculated sample size was multiplied by a design effect of 1.5 due to cluster sampling. Considering a 10% loss to follow up, the final sample size was 770 pregnant women (385 of the control group and 385 of the intervention group), which were included in the trial. Due to problems reported in Figure 1, the actual data from 372 women in the intervention group and 372 women in the control group were collected. The study population was pregnant women aged 18–49 years and in their first trimester of pregnancy and permanent residents (who lived in the study area for more than six months) of the selected clusters (Got’s), which are the smallest structural units in the Ambo district. Pregnant women with chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS, those with incomplete baseline data, and those enrolled in supplementary feeding programs were excluded from the study, as these interventions would have an impact on dietary practice and thus bias the results of the study.

Recruitment, randomization and intervention allocation

Recruitment of participants

A multi-stage sampling technique was used to select study participants. The total number of kebele in the district was stratified into rural and urban areas. Simple random sampling (SRS) with the lottery method was used to select 12 kebeles (2 urban and 10 rural) from the existing 39 kebeles (6 urban and 33 rural). Each kebele has its own clusters (Gots), which have been pre-determined by government bodies and are grouped into 149 distinct clusters. The number of clusters in each kebele was then recorded. Noncontiguous cluster lists were created, and 48 clusters were chosen at random from the total number of clusters available in the district. As a result, this study included 24 clusters per arm. To obtain clusters from each kebele, we employed a proportionate stratified sampling strategy. Eligible pregnant women were screened utilizing a family folder prepared by the kebele's health extension workers (HEWs), as well as by inquiring about the first date of their last menstrual cycle and confirming pregnancy using a pregnancy test. Equal numbers of participants were selected from each cluster. The study covered all pregnant women who were eligible. Those women who gave consent to participate in the study were included and requested to sign an informed consent to ensure voluntary participation. After consent was obtained, each participant was interviewed.

Randomization

Random selection of clusters

The clusters (i.e. sub kebeles or locally known as “Gots”) were the units of randomization in our study. Before randomization, we stratified the district by the sub district (locally known as “Kebeles”, i.e., Urban vs. rural Kebeles) and created a separate list of Kebeles. Each kebele was given a unique cluster code. As stated above, the Ambo district is divided into 39 sub-districts (Kebeles). Using simple random sampling (SRS) with the lottery method, we selected 12 kebeles. Each kebele has sub kebeles (Gots). We used proportionate stratified sampling method to obtain Gots, from each of the 12 kebeles proportionately (48/149) to their population size. Each cluster was assigned a unique cluster code. Then, the Author assigned the 48 clusters in to two blocks of size four according to the order they appeared alphabetically. The Author randomly selected the randomization sequence of clusters for each block using the sealed lots of the six possible permutations within the block. The clusters in each block randomly assigned to intervention and control arms according to the randomization sequence evident by the selected permutation within the block for the stratum. Consequently, we formed 24 clusters for the intervention arm and 24 clusters for the control arm, maintaining a 1:1 random allocation ratio. Both the stratification and randomization techniques helped actual and potential confounding factors be distributed evenly across the study arms, which eventually ensured comparability of the arms. In one cluster, all eligible pregnant women were enrolled in the same arm (either in the intervention or control arms). The typical cluster size was 12–17 pregnant women. To minimize information contamination, buffer zones (non-selected clusters) were also left between the intervention and control clusters. The Author randomized the clusters; Health Extension workers screened, enrolled and assigned the participants to interventions. Thirteen people from the intervention and thirteen from the control groups were removed from the study for reasons such as discontinuing the intervention and being lost to follow-up. The study was completed with 744 people (Fig 1).

Blinding

Allocation concealment is not possible due to the nature of the intervention. The participants, as well as the HDAs, are aware of the intervention. However, the participants, HDAs, and data collectors were blinded to the study hypothesis. The field supervisors were blinded to the outcome of interest and, finally, we blinded the data collectors to the intervention. Furthermore, the data entry clerk was blinded by coding the groups.

Intervention

To continue with the intervention strategy, the researchers recruited Health Development Armies (HDAs). HDAs were chosen from clusters that had been designated as intervention groups. Following recruitment, HDAs were trained for one week using a protocol developed by the principal investigator for pregnant women based on the Essential Nutrition Action framework and FANTA [6,34]. Both theoretical and practical demonstrations were included in the training. HDAs followed the criteria (based on the protocol) to assure the intervention's adoption. A training handbook, role-playing, participatory meal preparation, and mock BCC sessions were used to deliver HDAs training to a group. To reduce variability among HDAs, the researchers established a key assessment question (checklist) (incorporating both theory and skill). The Health Development Army's knowledge and skills were assessed before and after training, as well as through practical evaluations. After the training, the authors conducted standardized tests to ensure that everyone was on a similar level. Furthermore, the researchers and supervisors actively monitored HDAs during the pretest and during the intervention to see if they were delivering the intended message according to the intervention protocol. Those who failed to communicate the health and nutrition BCC messages were identified and prompt corrective action was taken. The intervention for pregnant women took place in the community's intervention clusters. However, the exact location of the BCC training was determined by agreement between the pregnant women and the HDA (so that they traveled to a common site but not out of the intervention clusters). The intervention was conducted once every two weeks for duration of 1:00 to 1:30 hours on nonworking days; similarly, the researchers monitored the intervention activities every two weeks, and the intervention lasted three months. The typical cluster size was 12-17 pregnant women, so one HDA was in charge of each cluster. The main components of the intervention were adapted from the recommendations by Essential Nutrition Action (ENA) and FANTA [6,34]. The core content of the intervention for dietary practice includes the following practice messages: on eating additional foods during pregnancy (increase meal frequency and portion size with gestational age), eating a variety (diversified) of foods from vegetable, fruit, and animal sources (follow from ten food groups) according to ENA and FAO recommendations [6,35]; drinking up to three liters of water; and cooking with oil. Similarly, at each BCC session, the consequences of not using the above message were discussed. During each BCC session, participants' knowledge and attitudes about good nutrition and health were also assessed. Then, depending on the detected gaps, a BCC intervention was delivered further. A message about food intake centered on locally available, acceptable, and affordable foods. In addition to delivering BCC messages, HDAs were provided posters and brochures with relevant images to display to pregnant women. Pregnant women were given leaflets with key messages written in Afan Oromo and Amharic (local) languages with illustrations. If a woman couldn't read, it was suggested that she have the leaflet read to her by someone at home or in the neighborhood who could. Because the selected HDAs were educated (at least primary education completed), they received written teaching aid; they had a schedule and topics to address in each contact (additional file 1). Each pregnant woman in the intervention group had attended six BCC sessions. Meal preparation and its variety are covered in a practical demonstration. Participants were urged to share food from their own kitchens (home) to demonstrate meal preparation. Based on this visual display, pregnant women actively identified the food groups and preparation methods they should change. All pregnant women who were classified as intervention groups began receiving the intervention in July of 2018. The intervention was given over three months, from July to September 2018. Pregnant women in the control groups did not receive the intervention but were instead exposed to the standard care provided by the healthcare system during an ANC visit and any intervention at the community level by health extension workers. This service was available to pregnant women in both the control and intervention groups. They were monitored for the same duration of the intervention and given the same evaluations as the intervention group.

Data collection tools and procedures

A semi-structured questionnaire prepared in English was used to collect data. The questionnaire was translated into two languages (Afan Oromo and Amharic) and then back to English by language experts to keep its consistency. The questionnaire was pretested in Ginchi town, which is nearby to Ambo district, on 39(5%) of the total sample size to identify any ambiguity, length, completeness, consistency, and acceptability of the questionnaire, and some skip patterns were corrected before the real data collection. Eight diploma nurses were recruited to collect data. Training was given to the data collectors on the objective and relevance of the study; confidentiality of information; respondent’s right; informed consent; and techniques of interview. The filled questionnaires were checked for consistency and completeness daily by four supervisors who had BSc degrees in Nursing and principal investigators on the spot. The questionnaire includes part one: socio-demographic and economic characteristics like age, marital status, residence, education, occupation, household’s size, food security and wealth index, and women’s decision-making power; Part two: maternal characteristics like years at marriage, parity, gravidity, and having health and nutrition information), Part three: knowledge, attitude and practices on dietary related issues of pregnant women. Questions related to knowledge and attitude on nutrition and health were adapted from essential nutrition action frame work and a framework for promoting maternal nutrition developed by the Manoff Group for developing countries [6,15,36]. The household wealth index was assessed using wealth constructs covering household assets, utilities, and agricultural land ownership adopted from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey [30]. The latent factors describing the wealth data were generated using principle components analysis (PCA), and then grouped into wealth terials [20]. Women’s decision-making power was assessed using eight questions. When a choice was made by the lady alone or jointly with her husband, code one was assigned to each question; otherwise, code zero was assigned to each question. The mean was used to categorize a woman's ability to make decisions [37]. Food security status was assessed using 27 previously validated questions [38]. A household that experienced less than the first 2, 2–10, 11–17, and > 17 food insecurity indicators was considered food secure, mildly, moderately, and severely food insecure households, respectively. The knowledge of pregnant women on nutrition and health was assessed by 14 questions using PCA. Each participant received a knowledge score based on the number of questions correctly answered in the knowledge assessment questions section. Each correct response received a 1, while each incorrect response received a 0. The factor scores were summed and ranked into tertiles (three parts). Then the highest tertile was labeled as a good knowledge, if not poor knowledge [39]. The attitude was assessed by 11 Likert scale questions using PCA. The factor scores were summed and ranked into tertiles (three parts). Then the highest tertile was labeled as a favorable attitude, if not an unfavorable attitude [20]. The primary outcome of this study was dietary practice. It included increased meal frequency and amount, dietary diversity score, and consumption of animal source foods, which were assessed using a semi-structured questionnaire developed and modified by ENA and FANTA [6,34]. The dietary diversity assessment tool captures detailed information about all foods and beverages consumed, including any snacks in the past 24 hours, with an estimation of the portion size from midnight to midnight, and the interviewer probes for any food types forgotten by participants. We combined all consumed food items into nine food groups based on their nutrients as: 1) grains, white roots, tubers, and plantains; 2) pulses (beans, peas, and lentils); 3) nuts and seeds; 4) dairy; 5) meat and fish (poultry and fish); 6) eggs; 7) dark green leafy vegetables; 8) vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; 9) other vegetables and fruits. The questionnaire was also validated after the assessment of locally available foodstuffs. One point was given for each food group consumed over the past 24 hours. Each food or beverage that the respondent mentioned was circled or underlined on a predefined list. The foods not included on the predefined list were either categorized by the principal investigator into an existing predefined food group or recorded in a separate place on the questionnaire and coded and organized later into one of the predefined food groups [34]. We did a four-day non-consecutive longitudinal dietary assessment [40] and the maximum possible score for each respondent was 40. The number of food groups the women ate within four non-consecutive days was counted to analyze the dietary diversity score (DDS). The dietary diversity score was converted into a tertile (three parts). Then the highest tertile was labeled as "high" dietary diversity score, if not "low" dietary diversity score [41]. The utilization of animal source food (ASF) was assessed by counting the frequency of each animal source food the women took within the four nonconsecutive days. Finally, the frequency of ASF consumption was divided into terciles and the highest tertile was used to define “high” ASF consumption, while the two lower tertiles combined were labeled as “low” ASF consumption [20]. Dietary diversity score, Animal Source Food consumption, and increased amount of meal (both in frequency and amount) were used to assess dietary practices. Optimal dietary practice: when women had increased amount of meal, high DDS, and high ASF consumption, whereas it was suboptimal when women had not increased amount of meal or low DDS or low ASF consumption [39]. The secondary outcomes of the study were nutritional status and birthweight. Baseline data were collected from all pregnant women (n=770) from June 1-21, 2018 and end point data were collected from pregnant women (n=744) in November, 2018.

Definition of terms

Diploma Nurses: are nurses expected to provide maternal and child health care and pre/post and intraoperative nursing care, to implement and monitor nursing care for clients with acute health problems, perform nursing process, administer and monitor medications, work in health care teams and independently within the realm of practice privileges stated in the Ethiopian Occupational Standard (EOS) [42].

Data processing and analysis

Before entering data, data were manually checked for completeness and consistency during data collection. Then it was entered into EPI data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS for Windows version 23 for cleaning and analysis. The effect of intervention was measured at the endpoint of follow-up.

Although the authors sought to apply a two-level intercept only multilevel model analysis, the likelihood ratio test performed to compare multilevel model analysis to ordinary log-binomial model analysis shows that the two models are similar (X2 (df = 1) = 0.0, p-value = 1.00). As a result, Authors determined that log binomial model analysis is preferable than multilevel analysis. The intra-cluster correlation (ICC) coefficient was also closer to zero (1.24 X 10 -17). This showed that almost 100% of the dietary practice scores were explained by individual level variables. The non-significant variability in dietary practices of pregnant women at the cluster level could be due to considering the design effect of 1.5 during sample size calculation, which in turn increased the calculated sample size. Therefore, a log-binomial model analysis was used to assess predictors for the two reasons described above. First, descriptive statistics like mean and standard deviation were done for continuous variables and frequency and percentage for categorical data. A chi-square test was performed to compare the baseline characteristics of the intervention and control groups. A proportion with their p-value was conducted to compare the dietary practices of pregnant women (before and after intervention). Multicollinearity was checked using Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) at < 10 but the VIF of all variables was less than two, which means no multicollinearity. Moreover, the interaction between variables and intervention group at a p-value of < 0.05 was assessed and there was no interaction. The study of effect measure was done using a log-binomial model analysis to estimate the adjusted relative risk and its 95% confidence interval (CI) of the risk factors for suboptimal dietary practice. Initially, independent variables were assessed for their association with the dependent variable one by one. Those independent variables with a p-value ≤0.2 were included in the log-binomial model. Statistical analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis, which is appropriate for a cluster randomized study design.

Data quality control

For one week, the health development armies were trained together. Data collectors and supervisors received three days of training as well. Four supervisors with BSc degrees in nursing and investigators supervised the HDA every two weeks. Furthermore, pregnant women in each cluster had the same number and frequency of BCC sessions, and the lengths of contact within each intervention group were similar, resulting in a standardized process. Participants were reminded of the necessity of attending all sessions and acting at home according to the protocol presented to prevent dropout and promote adherence to the intervention and follow-up program. The HDA monitored and recorded adherence to the BCC sessions in a personal training diary (attendance sheet). The intervention process was pretested before the implementation of the trial. Every two weeks, HDAs and their supervisors met to discuss and provide possible remedies to the problems that arose during BCC sessions. The data were collected using a pre-tested questionnaire. Cronbatch's alpha value for knowledge and practice > 0.7 was obtained for the entire scale of the instrument, indicating that it is suitable for use in the research domain. The questionnaire was also translated into the most widely spoken languages in the study area (Afan Oromo and Amharic) to aid respondents' comprehension. The data gathering process were thoroughly monitored by supervisors and the principal investigator. Daily, completed questionnaires were reviewed for completeness, and any missing or incorrect information was updated. Field supervisors randomly evaluated 5% of the data and alerted them to a possible measurement issue [40].

Results

From 770 pregnant women who enrolled in this study, 744(96.6%) (372 in the intervention group and 372 in the control group) were included in the analysis. Thirteen pregnant women discontinued the intervention from the intervention group due to the following reason: like six women didn’t attend all BCC sessions, four changed their mind to participate in the intervention, two moved out of the area, and one woman developed a miscarriage. Similarly, thirteen pregnant women lost to follow up from the control group due to the following reasons; like eight women moved out of the area, three changed their mind, and two women develop miscarriage (Figure 1). All pregnant women who were classified as intervention groups began receiving the intervention on July 01, 2018. The intervention was given over three months, from July 01, 2018 to September 30, 2018. At the baseline, there was no significant difference in all socio-demographic and obstetric-related characteristics between the intervention and control groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Figure 1: This diagram depicts the flow of study participants through the trial according to the criteria recommended in the CONSORT guideline.

|

Variable |

Category |

Intervention group (n1=372) |

Control group (n2=372) |

p |

|

Number of clusters |

24 |

24 |

||

|

Residence |

Rural |

296(49.1) |

307(50.9) |

0.303 |

|

Urban |

76(53.9) |

65(46.1) |

||

|

Religion |

Protestant |

153(48.4) |

163(51.6) |

0.228 |

|

Orthodox |

169(49.1) |

175(50.9) |

||

|

Others |

37(44.0) |

47(56.0) |

||

|

Age of the respondent |

18-24 Years |

90 (50.6) |

88(49.4) |

0.56 |

|

25-34 Years |

256(50.0) |

256 (50.0) |

||

|

>35 Years |

23 (42.6) |

31 (57.4) |

||

|

Respondents’ Occupation |

Employed |

19 (47.5) |

21 (52.5) |

0.868 |

|

House wives/ Daily laborers |

307 (50.2) |

305 (49.8) |

||

|

Merchants |

23 (54.8) |

19 (45.2) |

||

|

Farmers |

22 (44.0) |

28 (56.0) |

||

|

Women educational status |

No formal education |

144 (50.7) |

140 (49.3) |

0.555 |

|

1-4 Grade |

83 (46.9) |

94 (53.1) |

||

|

5-8 Grade |

92 (50.5) |

90 (49.5) |

||

|

9-12 Grade |

40 (54.1) |

34 (45.9) |

||

|

Diploma and higher |

10 (37.0) |

17 (63.0) |

||

|

Husband educational status |

No formal education |

112 (51.6) |

105 (48.4) |

0.68 |

|

1-4 Grade |

72 (51.4) |

68 (48.6) |

||

|

5-8 Grade |

95 (50.5) |

93 (49.5) |

||

|

9-12 Grade |

66 (46.2) |

77 (53.8) |

||

|

Diploma and higher |

24 (42.9) |

32 (57.1) |

||

|

Household size |

1-3 house hold size |

114 (54.0) |

97 (46.0) |

0.15 |

|

4-5 house hold size |

176 (49.7) |

178 (50.3) |

||

|

>5 house hold size |

79 (44.1) |

100(55.9) |

||

|

Household wealth tertile |

Low |

110 (50.5) |

108 (49.5) |

0.92 |

|

Medium |

159 (48.8) |

167 (51.2) |

||

|

High |

100 (50.0) |

100 (50.0) |

||

|

Food security status |

Unsecured |

133(47.5) |

147(52.5) |

0.426 |

|

Secured |

236(50.8) |

228(49.2) |

||

|

Estimated time to reach health institution |

< 30 minutes |

77(50.0%) |

77 (50.0%) |

0.98 |

|

30-60 minutes |

147 (49.8) |

148 (50.2) |

||

|

> 60 minutes |

145 (49.2) |

150 (50.8) |

||

|

Parity |

<=1 live birth |

109(48.0) |

118(52.0) |

0.659 |

|

2-4 live births |

230(50.9) |

222(49.1) |

||

|

>=5 live births |

30(46.2) |

35(53.8) |

||

|

Gravidity |

<=2 pregnancy |

58(49.6) |

59(50.4) |

0.876 |

|

3-4 pregnancy |

232(50.2) |

230(49.8) |

||

|

>=5 pregnancy |

79(47.9) |

86(52.1) |

||

|

Women’s decision-making power |

Suboptimal |

116(51.1) |

111(48.9) |

0.691 |

|

Optimal |

256(49.5) |

261(50.5) |

||

|

Optimal |

103(52.3) |

94(47.7) |

Table 1: Selected Characteristics of pregnant women in control and intervention groups at the beginning of the study, Ambo district, Ethiopia, 2018

Dietary Practice of pregnant women at (Baseline and endline measurement)

Prior to the intervention, the dietary practices of the study subjects were comparable (p = 0.552). At the end of the trial, a lower proportion of women in the intervention group (36.2% vs. 63.8%, p<0.001) had suboptimal dietary practice than their counterparts (Table 2). At the end of the intervention, each component of the dietary practice of the study subject was improved. After the implementation of the BCC intervention through the health development armies, pregnant women increased their meals both in frequency and amount (65.2%) in the intervention group, vs. 34.8% in the control group (p<0.001). Similarly, after the intervention, a higher proportion of women in the intervention group (79.5% vs. 20.5%, p<0.001) had a higher dietary diversity score than their counterparts. Likewise, after the intervention, a higher proportion of women in the intervention group (63.0% vs. 37.0%, p<0.001) had higher ASF consumption than their counterparts. Finally, the overall optimal dietary practice of pregnant women after the intervention was also significantly improved (65.1%, 95%CI: 60.3, 69.5% vs. 34.9%, 95%CI: 29.1, 40.2%) when compared to the control group. The difference in proportion of dietary practice between the intervention and control group was statistically significant (p<0.001) (Table 3).

|

Variables |

Category |

Intervention (n1 = 372) N (%) |

Control (n2=372) N (%) |

p |

|

Dietary practice before intervention |

suboptimal |

270(49.7) |

276(50.3) |

0.552 |

|

Optimal |

102(52.1) |

96(47.9) |

||

|

Dietary practice after intervention |

suboptimal |

141(36.2) |

248(63.8) |

<0.001 |

|

Optimal |

231(65.1) |

124(34.9) |

Table 2: Dietary practice (baseline and endline measurement) of pregnant women in Ambo district, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2018

|

Variables |

Category |

Intervention (n1 = 372) N (%) |

Control (n2=372) N (%) |

p |

|

Amount of meal |

Not increased |

250(44.9) |

307(55.1) |

<0.001 |

|

Increased |

122(65.2) |

65(34.8) |

||

|

Dietary Diversity Score |

Low |

256(42.8) |

342(57.2) |

<0.001 |

|

High |

116(79.5) |

30(20.5) |

||

|

Consumption of ASF |

Low |

256(45.7) |

304(54.3) |

<0.001 |

|

High |

116(63.0) |

68(37.0) |

||

|

Overall Dietary Practice |

Suboptimal |

141(36.2) |

248(63.8) |

<0.001 |

|

Optimal |

231(65.1) |

124(34.9) |

Abbreviation: ASF, Animal source food

Table 3: Dietary practice at endpoint of the study among pregnant women in Ambo district, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2018

Risk factors of suboptimal dietary practice at endpoint of the study among pregnant women in Ambo district

Simple log-binomial model Analysis showed that there was an association between dietary practice of pregnant women and study group, residence, age at marriage, respondent educational status, wealth, food security status, estimated time to reach health institution, number of ANC, knowledge about nutrition and health, and attitude towards nutrition and health. Whereas, religion, age of the respondent, marital status, ethnicity, respondent occupation, household size, number of previous birth, number of pregnancy, and gap duration between pregnancy had no association with dietary practice of pregnant women. However, study group, respondent educational status, food security status, estimated time to reach health institution, knowledge about nutrition and health, and attitude towards nutrition and health were found significantly associated with dietary practice in multivariable log-binomial model analysis (p<0.05) (Table 4). The study group (being in the intervention group) was found to have a significant association with the dietary practices of pregnant women. Pregnant women who received intervention were 40.9% less likely to be at risk of being suboptimal in dietary practice compared to pregnant women who were in the control group (ARR = 0.591, 95%CI: 0.510-0.686). Those pregnant women who had 5-8 grade were 15.8% less likely to be at risk of being suboptimal in dietary practice compared with those with no formal education (ARR = 0.842, 95%CI: 0.726-0.976) and those pregnant women who had secondary and above education were 55.6% less likely to be at risk of being suboptimal in dietary practice compared with those with no formal education (ARR =0.444, 95%CI: 0.318-0.620). Pregnant women from food-secure households were 57.9% less likely to be at risk of being suboptimal in dietary practice compared to unsecured pregnant women (ARR = 0.421, 95% CI: 0.327-0.567). Pregnant women who travel 30-60 minutes to reach a health institution were 1.3 times more likely to be at risk of being suboptimal in dietary practice compared to pregnant women who travel less than 30 minutes (ARR = 1.300, 95% CI: 1.072-1.578) and pregnant women who travel more than 60 minutes to reach a health institution were 1.2 times more likely to be at risk of being suboptimal in dietary practice compared to pregnant women who travel less than 30 minutes (ARR = 1.271, 95% CI: 1.051-1.537). Pregnant women who had good knowledge of nutrition and health were 32.9% less likely to be at risk of being suboptimal in dietary practice compared to pregnant women who were in their counterparts (ARR=0.671, 95%CI: 0.565-0.734). The study also revealed that those pregnant women who had a favorable attitude towards nutrition and health were 25.0% less likely to be at risk of being suboptimal in dietary practice compared to pregnant women who were in their counterparts (ARR = 0.750, 95%CI: 0.584-0.844).

|

Variable |

Category |

Dietary practice |

CRR(95% CI) |

ARR(95%CI) |

|

|

Optimal N (%) |

Suboptimal N (%) |

||||

|

Study group |

Control |

124(33.3) |

248(66.7) |

1 |

1 |

|

Intervention |

231(62.1) |

141(37.9) |

0.569(0.490-0.660) |

0.591(0.510-0.686)* |

|

|

Residence |

Rural |

273(45.3) |

330(54.7) |

1 |

1 |

|

Urban |

82(58.2) |

59(41.8) |

0.765(0.621-0.941) |

0.981(0.807-1.192) |

|

|

Age at marriage |

Less than 18 |

55(40.7) |

80(59.3) |

1 |

1 |

|

18-24 years |

276(48.2) |

297(51.8) |

0.875(0.745-1.027) |

0.953(0.605-1.502) |

|

|

>24 years |

24(66.7) |

12(33.3) |

0.563(0.347-0.911) |

0.685(0.350-1.977) |

|

|

Respondents’ Occupation |

Employed |

25(61.0) |

16(39.0) |

1 |

1 |

|

House wives |

276(46.1) |

323(53.9) |

1.382(0.936-2.040) |

0.972(0.660-1.430) |

|

|

Merchants/ Daily laborers |

34(63.0) |

20(37.0) |

0.949(0.566-1.592) |

0.772(0.484-1.233) |

|

|

Farmers |

20(40.0) |

30(60.0) |

1.538(0.986-2.398) |

1.041(0.692-1.565) |

|

|

Respondent educational status |

No formal education |

109(38.7) |

173(61.3) |

1 |

1 |

|

1-4 Grade |

78(43.8) |

100(56.2) |

0.916(0.781-1.074) |

0.928(0.829-1.039) |

|

|

5-8 Grade |

88(48.6) |

93(51.4) |

0.838(0.707-0.992) |

0.842(0.726-0.976)* |

|

|

Secondary and above |

80(77.7) |

23(22.3) |

0.364(0.251-0.528) |

0.444(0.318-0.620)* |

|

|

Wealth status |

Poor |

94(43.3) |

123(56.7) |

1 |

1 |

|

Medium |

142(43.4) |

185(56.6) |

0.998(0.859-1.160) |

0.968(0.848-1.106) |

|

|

Rich |

119(59.5) |

81(40.5) |

0.715(0.582-0.876) |

0.725(0.598-1.179) |

|

|

Food security status |

Unsecured |

54(17.9) |

247(82.1) |

1 |

1 |

|

Secured |

301(67.9) |

142(32.1) |

0.391(0.338-0.452) |

0.421(0.327-0.567)* |

|

|

Estimated time to reach Health institution |

<30min |

87(56.1) |

68(43.9) |

1 |

1 |

|

30-60 min |

131(44.6) |

163(55.4) |

1.264(1.029-1.552) |

1.300(1.072-1.578)* |

|

|

>60 min |

137(46.4) |

158(53.6) |

1.221(0.992-1.502) |

1.271(1.051-1.537)* |

|

|

Number of ANC visit |

<4 visit |

221(55.3) |

179(44.8) |

1 |

1 |

|

>4 visit |

91(70.0) |

39(30.0) |

0.670(0.505-0.891) |

0.809(0.613-1.068) |

|

|

Parity |

1-2 live birth |

160(45.3) |

193(54.7) |

1 |

1 |

|

3-4 live birth |

103(47.5) |

114(52.5) |

0.961(0.820-1.126) |

1.001(0.872-1.149) |

|

|

>5 live birth |

92(52.9) |

82(47.1) |

0.862(0.717-1.036) |

0.909(0.773-1.069) |

|

|

Knowledge on nutrition and health |

Poor |

137(34.2) |

264(65.8) |

1 |

1 |

|

Good |

218(63.6) |

125(36.4) |

0.554(0.473-0.647) |

0.671(0.565-0.734)* |

|

|

Attitude on nutrition and health |

Unfavorable |

196(41.2) |

280(58.8) |

1 |

1 |

|

Favorable |

159(59.3) |

109(40.7) |

0.691(0.587-0.814) |

0.750(0.584-0.844)* |

|

Notes: *Significant at p-value <0.05. Parameter estimates were adjusted for the tabulated variables.

N: Number, Abbreviations: CRR, crude relative risk; ARR, adjusted relative risk, CI: Confidence Interval

Table 4: Result of the log-binomial model to identify risk factors for suboptimal dietary practice among Pregnant women at endpoint in Ambo district, Ethiopia, 2018, (n=744)

Discussion

This trial aimed to compare the effect of BCC using the health development armies to the normal standard of the intervention obtained from the health care system and any intervention at the community level by health extension workers. The socio-demographic, obstetric, and dietary practices of pregnant women were similar at the baseline. The end result will be used by other maternal health organizations to design programs aimed at improving dietary practices among pregnant women as a method to improve maternal nutritional status in the district and other places with comparable circumstances. The findings of this study confirmed the effectiveness of BCC through the health development army in improving the dietary practices of pregnant women. Behavioral change and communication intervention were effective in improving dietary practice [19,20]. In line with this fact, the finding showed there was a significant improvement in dietary practices of the pregnant women in the intervention group compared with the control group. This study is in line with the study done among pregnant women in Indonesia that revealed providing nutrition education through small groups with interactive methods improves the nutritional habits of pregnant women [21]. Similarly, one study in Ethiopia showed the positive significant effect of BCC intervention to promote healthy dietary practice during pregnancy [22]. As a result, BCC via the health development armies appears to be a promising strategy for filling gaps in health education and counseling provided at health facilities by health professionals. The difference between intervention and control groups might be that the intervention was based on practical demonstration, which is a unique and promising technique of behavior change communication. Health development armies used a BCC guide based on ENA frame works, and FANTA [6,34]. Our intervention (i.e., BCC message on nutrition and health) was also supported by a health behavior change communication theory, the "Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction," which states that a person's strong desire to perform a behavior, coupled with the necessary skills and abilities to perform it, in the presence of a favorable environment, results in the desired behavior change [43]. This behavior change communication message includes a practical demonstration (visual, interactive, participatory, and skillful) in addition to a theoretical aspect. This strategy was supported by the findings that stated interventions that focus on improving real behavior or behaviors that are necessary for behavior change are more effective than those that focus solely on information [44]. Behavior change and communication through the health development army is less expensive, does not require food supplements, and appropriate intervention is carried out at the community level to improve the dietary practices of pregnant women. It is also more likely to be sustainable in resource-poor countries like Ethiopia. The other difference between intervention and control groups regarding the dietary practices of pregnant women might be that the nutrition education delivered by the health care system (i.e., for control) might not be comprehensive enough within the ANC setting due to time management constraints. This is supported by a systematic review on the processes and outcomes of antenatal care that found ANC education sessions were conducted hastily and in less supportive ways due to a lack of time and inadequate skills [44]. Another reason could be that our intervention can boost pregnant women's confidence and efficacy because it includes both theoretical and practical components. Furthermore, we conducted our intervention in their community by grouping pregnant ladies, which resulted in a more facilitated discourse to promote communication and involvement among the pregnant women. Generally, the findings of this study showed that BCC through the health development armies was successful in improving women’s dietary practices. Unlike this intervention, nutrition education given by the health system was not effective in improving the dietary practices of pregnant women. This difference is due to the techniques in health education. Our intervention used intervention protocol (i.e. a training handbook, role-playing, participatory meal preparation, and mock BCC sessions). This is also supported by the research finding that BCC is widely recognized as one of the main health promotion strategies. It is an interactive process of working with individuals and communities to develop communication strategies to promote positive behaviors as well as create a supportive environment to enable them to adopt and sustain positive behaviors [8,45]. However, education given by the health care system does not use the mentioned technique. Therefore, these results suggest the BCC through the health development armies using the intervention protocol at the community level following close and supportive supervision improves the dietary practices of pregnant women.

Limitation

This study admits the following limitations: due to the nature of the intervention, allocation concealment was not achievable; nonetheless, the participants, health development armies, and data collectors were blinded to the study hypothesis. Besides, there was no research on the health development army's BCC's effect on pregnant women's dietary practices, making it difficult to make direct comparisons.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that behavior change communication through the health development army using the guide of ENA frame works, and FANTA nine food group approaches is effective in improving the dietary practices of pregnant women. As a result, providing BCC on dietary-related issues through the Health Development Armies by grouping pregnant women in their community is recommended to enhance the dietary practices of pregnant women.

Abbreviations

ANC: Antenatal Care; AOR: Adjusted Odd Ratio; BCC: Behavior Change Communication; CI: Confidence Interval; CONSORT: Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; COR: Crude Odd Ratio; CRCCT: Cluster Randomized Controlled Community Trial; EDHS: Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey; ENA: Essential Nutrition Action; HAD: Health Development Army; HEW: Health Extension Worker; IYCF: Infant and Young Child feeding Practice.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods in the study were performed in accordance with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines. This study is a community trial that was registered with the Pan African Clinical Trial Registry. The date of registration was 03/05/2018. The registry's unique identification number is (PACTR201805003366358). The results were reported using the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines (additional file 2). The Jimma University Ethical Review Committee reviewed and approved the study protocol (ref no: RPGC/40724/2016). Permission to conduct the study in the respective kebeles was granted by the Ambo district health office (ref no: ADHO/134/2018). Prior to participation in the study, the nature of the study was clearly disclosed to the study participants in order to gain their written informed consent (fingerprint for those who could not read and write) was secured from the study participants, and all information obtained was kept anonymous. Soft copy data is password protected, while hard copy data is secured with a key and lock to guarantee confidentiality. Personally identifiable information will not be used in any form in the presentation of the findings.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All the data related to this research are available in the text, tables or figures.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding source for this research

Authors’ contributions

MA: conceived and designed the study; conducted statistical analysis and result interpretation; prepared the manuscript. The author read and approved the manuscript.

TB: conceived and designed the study, conducted statistical analysis and result interpretation, and prepared the manuscript. The author read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to West Shewa zone and Ambo district personnel for providing permission to conduct the study, as well as to the supervisor and data collectors who committed themselves throughout the study period.

Our thanks also go to all the authors who have made available their published articles free of charge for our literature review. Finally, we would like to express our gratitude to all participants who voluntarily participated in the study.

References

- Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA. Maternal and Child Under nutrition Study Group. Maternal and child under nutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 12 (2008): 243-260

- Lee SE, Talegawkar SA, Merialdi M, et al. Dietary intakes of women during pregnancy in low- and middle-income countries. Public Health Nutr 16 (2013): 1340-1353.

- Gernand AD, Schulze KJ, Stewart CP, et al. Micronutrient deficiencies in pregnancy worldwide: health effects and prevention. Nat Rev Endocrinol 12 (2016): 274-289.

- WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience (2016).

- The MANOFF GROUP (MOG). Guidance for Formative Research on Maternal Nutrition: Prepared for the Infant and Young Child Nutrition Project (2011) pp: 4-6.

- Essential Nutrition Actions: Improving maternal, newborn, infant and young child health and nutrition, Geneva (2013): 3-45.

- Canavati SE, Zegers de Beyl, CLy P, et al. Evaluation of intensified behaviour change communication strategies in an artemisinin resistance setting. Malaria Journal 15 (2009): 249.

- Middleton PF, Lassi ZS, Son T, et al. Nutrition interventions and programs for reducing mortality and morbidity in pregnant and lactating women and women of reproductive age: A systematic review Australian Research Centre for Health of Women and Babies (ARCH), Robinson Institute. The University of Adelaide (2013): 20-30.

- Shuayib S, Alemayehu A, Beakal Z. Dietary practice and nutritional status among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Mettu Karl Referral Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. The Open Public Health Journal 12 (2020): 13-28.

- Mahlet Y, Mahlet B, Yohannes A. Dietary practices and their determinants among pregnant women in Gedeo Zone, Southern Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Dove Press journal: Nutrition and Dietary Supplements 12 (2020): 267-275.

- Tolera B, Mideksa S, Dida N. Assessment of dietary practice and associated factors among pregnant mother in Ambo District, West Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2018. Ethiop J Reprod Health 10 (2018): 43-51.

- Dalky H, Qandil A, Alqawasmi A. Factors associated with Undernutrition among pregnant and lactating Syrian refugee women in Jordan. . Global J Health Sci 10 (2018): 1-58.

- Biswas T, Townsend N, Magalhaes RS, et al. Current Progress and Future Directions in the Double Burden of Malnutrition among Women in South and Southeast Asian Countries. Curr Dev Nutr 3 (2019): 26.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ehiopia, USAID. A Tool to Support Nutrition Advocacy in Ethiopia: Ethiopia Profiles Estimates, Final Report, (2012): 15-25.

- Guyon AB. Essential nutrition action frame work. Training guide for health workers. Core Group, Washington DC (2011).

- USAID/Engine, Save the children. Maternal diet and nutrition practices and their determinants engine: A project supported by the Feed the Future and Global Health Initiatives A report on formative research findings and recommendations for social and behavior change communication programming in the Amhara, Oromia, SNNP and Tigray regions of Ethiopia (2014): 5-10.

- USAID, JSI. Understanding the Essential Nutrition Actions and Essential Hygiene Actions Framework (2015): 1-5.

- UNICEF conceptual framework of undernutrition (2016).

- Mohammadimanesh A, Rakhshani F, Eivazi R, et al. Effectiveness of educational intervention based on theory of planned behavior for increasing breakfast consumption among high school students in Hamadan. J Educ Community Health 2 (2015): 56-65.

- Yeshalem MD, Getu DA, Tefera B. Dietary practices and associated factors among pregnant women in West Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 20 (2020): 18.

- Tria Astika Endah Permatasari, Fauza Rizqiya, Walliyana Kusumaningati, Inne Indraaryani Suryaalamsah, Zahrofa Hermiwahyoeni. The effect of nutrition and reproductive health education of pregnant women in Indonesia using quasi experimental study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 21 (2021): 180-201.

- Diddana TZ, Kelkay GN, Dola AN, et al. Effect of nutrition education based on health belief model on nutritional knowledge and dietary practice of pregnant women in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia: A Cluster Randomized Control Trial. J Nutr Metab 11 (2018): 56-69.

- Saldanha LS, Buback L, White JM, et al. Policies and program implementation experience to improve maternal nutrition in Ethiopia. Food Nutr Bull 33 (2012): S27-50.

- Ethiopian mini Demographic and Health Survey, Important Profile (2019).

- Behavior change communication. Academy for International Development (2018).

- JU, UG, LSHTM. Jimma University, University of Glasgow (UG), London School of hygiene and tropical Medicine (LSHTM), Facilitating accessible community-oriented health systems: the Health Development Army in Ethiopia (2016).

- Central Statistical Authority [Ethiopia], ORC Macro. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (2000).

- Central Statistical Authority [Ethiopia], ORC Macro. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (2005).

- Central Statistical Authority [Ethiopia], Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey key finding. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (2011).

- CSA, ICF. Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF, Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland: CSA and ICF (2016).

- West Shoa Zone. West Shoa Zone, Health Office (2017).

- The National regional government of Oromiya. Physical and socio-economic profile of West Shewa zone and districts (2011).

- Fekadu B, Gemeda, Habtamu F. Assessment of Knowledge and practice of Pregnant Mothers on Maternal Nutrition and Associated Factors in Guto Gida Woreda, East Wollega Zone, Ethiopia. J Nutrition & Food Sciences (2015).

- FANTA III. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance, Participant-Based Survey Sampling Guide for Feed the Future Annual Monitoring Indicators (2018).

- Guidelines for measuring individual and household dietary diversity (2011).

- The MANOFF GROUP (MOG). Guidance for Formative Research on Maternal Nutrition: Prepared for the Infant and Young Child Nutrition Project 12 (2011): 4-6.

- CSA, ICF. Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF, Ethiopia demographic and health survey. Addis Ababa and Rockville: CSA and ICF (2016).

- Gebreyesus SH, Lunde T, Mariam DH, et al. Is the adapted Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) developed internationally to measure food insecurity valid in urban and rural households of Ethiopia? BMC Nutrition 18 (2015): 69-78.

- Belachew T, Lindstrom D, Gebremariam A, Hogan D, Lachat C, L. H. Food insecurity, food based coping strategies and suboptimal dietary practices of adolescents in Jimma zone Southwest Ethiopia. Plos One 8 (2013): e57643.

- Morseda C, Camille RG, Ashraful A, et al. Making a balanced plate for pregnant women to improve birth weight of infants: a study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial in rural Bangladesh. BMJ Open 9 (2017): 23-36.

- Workicho A, Belachew T, Feyissa GT, et al. Household dietary diversity and animal source food consumption in Ethiopia: evidence from the 2011 welfare monitoring survey. BMC Public Health 16 (2015): 1192.

- System Model Curriculum Health Care Giving Level IV Based on Occupational Standard (OS), Adama, Ethiopia (2012).

- Beiguelman B, Colletto GMDD, Franchi-Pinto. Birthweight of twins, the fetal growth patterns of twins and singletons. Genet Mol Biol 21 (1998): 151-154.

- Downe S, Finlayson K, Tuncalp O, et al. What matters to women: a systematic scoping review to identify the processes and outcomes of antenatal care provision that are important to healthy pregnant women. BJOG 123 (2016): 529-39.

- Canavati SE, Zegers de Beyl, CLy P, et al. Evaluation of intensified behaviour change communication strategies in an artemisinin resistance setting. Malaria 15 (2016): 249-258.