Determinants of Malnutrition among Under-Five Children in Bangladesh: Evidence from Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, 2019 Data

Article Information

Md. Momin Islam1*, Md. Tamzid Islam2, Farha Musharrat Noor3

1Lecturer, Department of Meteorology, University of Dhaka, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh

2Department of Statistics, University of Dhaka, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh

3Department of Statistics, University of Dhaka, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh

*Corresponding author: Md. Momin Islam, Lecturer, Department of Meteorology, University of Dhaka, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh.

Received: 17 May 2021; Accepted: 26 May 2022; Published: 01 June 2022

Citation: Md. Momin Islam, Md. Tamzid Islam, Farha Musharrat Noor. Determinants of Malnutrition among Under-Five Children in Bangladesh: Evidence from Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, 2019 Data. Fortune Journal of Health Sciences 5 (2022): 284-295

Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Malnutrition is a severe burden on the growth of under-five-aged children, notably in developing countries like Bangladesh. This study aims to investigate the determinants of malnutrition amid 0-5 years, aged children in Bangladesh using the data from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), 2019.

Material and Methods: This study observes child malnutrition status using Stunting (Height-for-age) from MICS 2019 data. The number of prenatal care mothers has been considered the key risk factor. Consequently, mother's and children's characteristics and socioeconomic conditions are also used to examine the association ships. Descriptive, Bi-variate, and multilevel logistic models were implemented to examine the prevalence of stunting and its association with the different levels of selected factors.

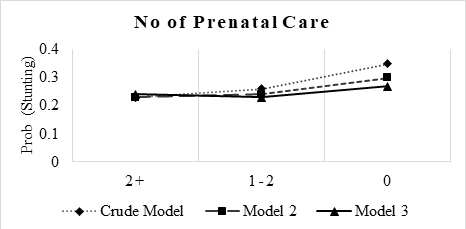

Results: Data showed that 26.5% of under-5 children in Bangladesh are stunted, and the prevalence of stunting is high for mothers with no prenatal care or just 1 and 2 prenatal care. However, the adjustment of prenatal care with other factors results in lower odds of being stunted. Among the other factors, mother's education, child age, place of delivery, sex of child, wealth index, and division were significantly impacted by stunting.

Conclusion: Authority should focus on mothers' personal development by improving their socioeconomic conditions to eradicate the complication of under-five child malnutrition in Bangladesh.

Keywords

Malnutrition, Under-five children, Stunting, Prenatal care, Bangladesh

Article Details

1. Introduction

Malnutrition is the most severe hazard to global public health, especially in low- and middle-income nations. It is characterized as a condition induced by an unbalanced diet in which specific nutrients are either deficient, excessive (too high), or in the wrong amounts. Poverty, hunger, and disease are all interconnected [1]. The nutritional status of children is an excellent indicator of a community's poverty level. Despite several government and non-government initiatives to address the issue, child malnutrition continues to be a primary concern in Bangladesh today [4].

In 2019, around 144 million, 47 million, and 38.3 million children under five were stunted, wasting, and overweight, respectively [2]. Malnutrition claims the lives of 60 percent of the world's 10.9 million children each year, with two-thirds dying before one [3]. Malnutrition increases the mortality risk from ARI (acute respiratory infection), diarrhea, measles, and other infectious illnesses [4]. Malnutrition can have long-term impacts on the brain and health in children under the age of five. Malnourished children grow up to be shorter and have fewer offspring. As a result, under-five malnutrition can have a significant influence on population growth [5-6]. Anthropometric measurements and biomarkers are utilized to assess nutritional status. Height-for-age (stunting), weight-for-height (wasting), and weight-for-age (wasting) are the three most prevalent physical growth indicators used to characterize children's nutritional condition (underweight). Stunting is a height-for-age measurement of less than minus two standard deviations from the median values of an internationally approved standard population. It is commonly seen as a sign of chronic malnutrition [7]. A weight-for-height indicator is used to diagnose acute malnutrition (wasting). Underweight or undernutrition is another kind of malnutrition defined by a weight-for-age indication [7,8].

Stunting (height-for-age) and wasting (weight-for-height) were detected in 21.3 percent and 6.9 percent globally, respectively [2]. A research-based on the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) 2014 [9] found that 36% of children under five are stunted, while 14% are wasting. The percentages of stunted children (28%) and wasted children (9.8%) have decreased in recent years as a result of several initiatives implemented by the Bangladeshi government and other organizations [10]. However, for a developing nation like Bangladesh, it is insufficient. Malnutrition among children under the age of five is a major problem for the Bangladeshi government and some foreign organizations. As a result, recognizing the risk factors for malnutrition in children under the age of five is crucial so that stakeholders may implement evidence-based policies to improve nutrition status. Identifying these traits and providing practical advice to improve nutrition has become one of the key responsibilities of public health professionals [11]. In the past, several techniques and statistical models were used to uncover probable causes of under-five child malnutrition. Over the preceding two decades, studies [12-22] conducted internationally and in developing countries such as Bangladesh identified low levels of maternal education, low socioeconomic status, and short prior birth intervals as potential risk factors for child malnutrition. This study investigated the number of prenatal care visits associated with chronic malnutrition among Bangladeshi children under five using MICS 2019 data.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Data source and study setting

The 'Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2019' database provided information on child malnutrition. Three decades ago, the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) launched the first MICS to provide comprehensive evidence-based on the lives of women and children. This was a critical step in looking into many issues that influence women and children's lives and boosted the statistical capacity to collect essential data on their lives. MICS 2019 is the sixth edition of the survey, performed using a two-stage stratified cluster sampling approach by the BBS in partnership with UNICEF Bangladesh from January to May 2019. There were 3,220 Primary Sampling Units (PSUs) chosen, and 64,400 households were counted. It includes national averages for the indicators mentioned earlier and statistically credible data for eight divisions and 64 districts based on socioeconomic axes such as gender, age, rural-urban divide, mother's educational attainment, functional difficulty, and wealth quintile. During the interview, anthropometric measurements were taken in order to get nutrition information for all live children under the age of five. To avoid connecting data from separate births, children with twin or multiple birth histories were removed from the study. As a result, anthropometric data from live children under the age of five are used in this study. More information is available in the MICS 2019 [10] report.

2.2 Variables

2.2.1 Dependent Variables

Children under the age of five have their nutritional status (nutritional deficit) examined using three separate anthropometric indices: stunting (low height-for-age), wasting (low weight-for-height), and underweight (low weight-for-height) (low weight-for-age). Stunting is a sign of chronic malnutrition, whereas wasting and being underweight are signs of acute malnutrition. Stunting has long-term and long-lasting negative impacts on a child's health and cognitive development [13, 22]. Focusing on the above issues, this study included only stunting as an outcome variable.

2.2.2 Covariates

A set of socioeconomic and demographic factors related to child malnutrition [11-22] were considered covariates. They were: area (urban, rural), division (Barisal, Chattogram, Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, Rangpur, and Sylhet), sex of child (boy and girl), mother educational status (pre-primary or none, primary, secondary, and higher secondary), mother age at birth (15-19, 20-24, 25-29, 30+), happy with life (not happy and happy), prenatal care (0, 1-2, 2+), wealth index (poor, middle, and rich), migration (never migrated, and ever migrated), ever used internet (yes and no), child age (<1, 1-3, and 3+), place of delivery (home, govt. hospital/clinic, and private hospital/clinic), birth order (1, 2-3, and 3+).

2.3 Statistical data analysis

The descriptive statistics of the variables addressed in the study were obtained using exploratory analysis. Bivariate analysis was also performed to determine how stunting scores changed when the covariate category changed. Finally, binary logistic regression models at various levels were fitted to determine the covariate-adjusted effects. It should be noted that factors discovered in bivariate analysis to have a statistically significant connection with stunting scores were only incorporated in the regression analysis. SPSS 25 was used for exploratory and bivariate analyses, while R programming was used for organizing the data and conducting regression analysis.

3. Results

3.1 Sample Characteristics

A total of 10490 children were selected in the sample, and 26.5% were stunned. Table 2 showed that all covariates except living area and migration status had a significant association with child stunting. Among the individuals, 20.5% belong to urban, and 79.5% belong to rural areas. Among eight divisions of Bangladesh, 23.0 % of the child belong to Dhaka, and at least 5.5% of the child belong to Barisal. The highest prevalence (35.2%) of stunned child found in the Sylhet division. The sampled number of boy and girl children is almost the same, whereas the boy child is compared to more malnourished than the girl child. The highest percentage (49.6 %) of the child comes from a secondary educated mother A higher educated mother-child is healthier than the others.

28.6% of a mother gave their first birth at 25-29. About 88.4% of women were happy with their life. Almost half of the women took prenatal care more than twice, and mothers who didn't take any prenatal care for their children suffered more nutritional deficiencies. Most women came from poor socioeconomic well-being and least of rich socioeconomic well-being. In higher wealth quintiles, children were less malnourished compared to the others. 86.7% of women used the internet throughout their life. 45.2% of the child were toddlers (2-3 years), 41.7% were infants (< 1 year), and 13.2% were preschoolers (3-5 years). Higher birth order children suffered more nutritional deficiencies. Most women (48.6%) gave their children birth at home. The children born at home had a higher prevalence of stunting than those born at government hospitals/clinics or private hospitals/clinics. About 89% of the individual had less or equal 3 children each. Note that covariates found to have a statistically significant association with stunting in bivariate analysis were only considered in the regression analysis.

Table1: The weighted prevalence of stunting by sample characteristics in Bangladesh 2019

|

Characteristic |

Sample Distribution (%) |

Stunting |

p-value |

|||||

|

Not Stunted |

Stunted |

|||||||

|

Overall |

10490(100) |

7766 (73.5) |

2724 (26.5) |

|||||

|

Area |

||||||||

|

Urban |

1898 (20.5) |

74.3 |

25.7 |

>0.05 |

||||

|

Rural |

8592 (79.5) |

73.3 |

26.7 |

|||||

|

Division |

||||||||

|

Barisal |

919 (5.5) |

74.4 |

25.6 |

<0.05 |

||||

|

Chattogram |

2217 (22.2) |

75.2 |

24.8 |

|||||

|

Dhaka |

2007 (23.0) |

72.9 |

27.1 |

|||||

|

Khulna |

1402 (10.0) |

80.8 |

19.2 |

|||||

|

Mymensingh |

670 (8.2) |

66.3 |

33.7 |

|||||

|

Rajshahi |

1041 (11.4) |

76.3 |

23.7 |

|||||

|

Rangpur |

1211 (10.4) |

74.4 |

25.6 |

|||||

|

Sylhet |

1023 (9.3) |

64.8 |

35.2 |

|||||

|

Sex of Child |

||||||||

|

Boy |

5263 (50.6) |

72.1 |

27.9 |

<0.05 |

||||

|

Girl |

5227 (49.4) |

75 |

25 |

|||||

|

Mother Educational Status |

||||||||

|

Pre-primary or none |

1025 (9.8) |

57.5 |

42.5 |

<0.05 |

||||

|

Primary |

2521 (23.9) |

67.7 |

32.3 |

|||||

|

Secondary |

5233 (49.6) |

76.9 |

23.1 |

|||||

|

Higher secondary+ |

1711 (16.7) |

81.1 |

18.9 |

|||||

|

Mother Age at Birth |

||||||||

|

15-19 |

2622 (25.6) |

72.9 |

27.1 |

<0.05 |

||||

|

20-24 |

2094 (19.9) |

75.2 |

24.8 |

|||||

|

25-29 |

3028 (28.6) |

75 |

25 |

|||||

|

30 |

2746 (25.9) |

71.3 |

28.7 |

|||||

|

Happy with Life |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Not Happy |

1250 (11.6) |

67 |

33 |

<0.05 |

||||

|

Happy |

9240 (88.4) |

74.4 |

25.6 |

|||||

|

Prenatal Care |

||||||||

|

0 |

2041 (18.6) |

63.5 |

36.5 |

<0.05 |

||||

|

1-2 |

3133 (30.5) |

73.8 |

26.2 |

|||||

|

2+ |

5316 (50.9) |

77 |

23 |

|||||

|

Wealth Index |

||||||||

|

Poor |

4793 (41.7) |

67 |

33 |

<0.05 |

||||

|

Middle |

3979 (38.4) |

76.9 |

23.1 |

|||||

|

Rich |

1718 (19.9) |

80.7 |

19.3 |

|||||

|

Migration |

||||||||

|

Never Migrated |

1991 (18.3) |

72.9 |

27.1 |

>0.05 |

||||

|

Ever Migrated |

8499 (81.7) |

73.7 |

26.3 |

|||||

|

Ever Used Internet |

||||||||

|

Yes |

1177 (13.3) |

79.5 |

20.5 |

<0.05 |

||||

|

No |

9313 (86.7) |

72.6 |

27.4 |

|||||

|

Child Age |

||||||||

|

<1 |

4307 (41.7) |

81.5 |

18.5 |

<0.05 |

||||

|

1-3 |

4798 (45.2) |

68.4 |

31.6 |

|||||

|

3+ |

1385 (13.2) |

65.9 |

34.1 |

|||||

|

Place of Delivery |

||||||||

|

Home |

5279 (48.6) |

68.6 |

31.4 |

|||||

|

Govt. hospital/Clinic |

1584 (15.5) |

74.9 |

25.1 |

<0.05 |

||||

|

Private hospital/Clinic |

3627 (35.9) |

79.6 |

20.4 |

|||||

|

Birth Order |

||||||||

|

1 |

3969 (38.0) |

74.4 |

25.6 |

<0.05 |

||||

|

2-3 |

5378 (51.0) |

74.4 |

25.6 |

|||||

|

3+ |

1143 (11.0) |

66.4 |

33.6 |

|||||

3.2 Multivariable associations between selected covariates and stunting

Table 2 shows the effect of care on stunting in a crude model and adjusted with the socioeconomic and personal characteristics of children and their corresponding mothers. In a crude model, it has found that the risk of being stunned was significantly 1.89 times (odds ratio (OR):1.89; 95% CI: 1.69,2.11) or (1.89-1)*100% = 89% higher among those children whose mother didn't take any prenatal care compared to the children whose mother took more than two times prenatal care. After adjusting to children's characteristics and their corresponding mothers, the odds of being stunted for children with mothers taking 1 or 2 care concerning more than two care has become insignificant. The OR for taking no care is still significant, but it is lower than observed in the crude model (OR: 1.4; 95% CI: 1.24, 1.58). Finally, we follow model 3, where socioeconomic conditions of women and index children have been included. Following model 2, OR has become lower but still significant for children whose mothers didn't take prenatal care than for children whose mothers took more than two times prenatal care (OR: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.04,1.34).

A mother's educational status plays an essential role in a child's nutritional status. Both model 2 and model 3 notified that the odds of pre-primary or primary educated mothers' children's nutritional status significantly differed from those of higher educated mothers. From model 2, Young mother children were more malnourished than the elder mother children, and the child of third or above birth order was more malnourished than the child of lower birth order. Use of the internet and mothers' happiness has not been found to have any role in the nutritional status of children. The boy child was more vulnerable to being malnourished compared to a girl child in both model 2 and model 3, and it was 1.23 times (OR: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.35) or (1.23 -1)*100% = 23% higher for boy child compared to the girl child. As the child's age increases, for example, toddlers and preschoolers had higher odds of being stunted compared to infants in both model 2 (Toddler - OR: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.08, 1.48, Preschooler - OR: 1.65; 95% CI: 1.40, 1.96) and model 3.

While comparing the stunting by divisions, we observed that children from Barisal and Khulna had significantly lower odds of being stunted than those of Dhaka as OR's < 1. Sylhet had significantly 1.28 or 28% higher odds (OR: 1.28; 95% CI: 1.07, 1.52) than Dhaka as OR >1. The children in the Sylhet division were significantly more malnourished than the other children. Changes in the Odds of being stunted in other divisions compared to Dhaka are insignificant. The place of delivery also showed a significant impact. Children born at home had 1.2 times (OR: 1.2; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.35) or 20% higher odds of being stunted than children born in private hospitals/clinics. This is odds is a bit higher- 1.21 times (OR: 1.21; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.40) or 21% for children born in government hospitals. The economic conditions also played an essential role in the nutritional status of under-five children. Children from middle and low-income families had significantly higher odds of being stunted (Middle- OR: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.08, 1.48, Poor- OR: 1.65; 95% CI: 1.40, 1.96) compared to the children who were born in Rich family.

Table 2: Estimates of regression coefficients and their 95% Confidence Interval (CI) and p-values obtained from the logistic regression model

|

Characteristic |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|

Prenatal care |

|

|

|

|

2+ |

|||

|

1-2 |

1.19 (1.07, 1.32)*** |

1.05 (0.95, 1.17) |

0.96 (0.86, 1.07) |

|

0 |

1.89 (1.69, 2.11)*** |

1.4 (1.24, 1.58)*** |

1.18 (1.04, 1.34)** |

|

Mother educational status |

|

|

|

|

Higher secondary+ |

|||

|

Secondary |

1.2 (1.03, 1.39)*** |

1.06 (0.92, 1.24) |

|

|

Primary |

1.74 (1.48, 2.06)*** |

1.37 (1.15, 1.64)*** |

|

|

Pre-primary or none |

2.35 (1.92, 2.87)*** |

1.75 (1.41, 2.16)*** |

|

|

Mother age at Birth |

|

|

|

|

29+ |

|||

|

25-29 |

1.07 (0.94, 1.22) |

1.04 (0.91, 1.18) |

|

|

20-24 |

1.19 (1.02, 1.38)** |

1.11 (0.95, 1.30) |

|

|

15-19 |

1.21 (1.02, 1.43)** |

1.15 (0.97, 1.36) |

|

|

Ever used Internet |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

|||

|

No |

1.08 (0.92, 1.27) |

0.94 (0.80, 1.11) |

|

|

Happy with Life |

|

|

|

|

Happy |

|||

|

Not Happy |

1.11 (0.97, 1.27) |

1.08 (0.94, 1.24) |

|

|

Birth order |

|

|

|

|

1 |

|||

|

2-3 |

1.03 (0.90, 1.16) |

1.02 (0.90, 1.16) |

|

|

3+ |

1.23 (1.01, 1.50)* |

1.15 (0.94, 1.41) |

|

|

Sex of Child |

|

|

|

|

Girl |

|||

|

Boy |

1.23 (1.13, 1.35)*** |

1.23 (1.13, 1.35)*** |

|

|

Child age |

|

|

|

|

<1 |

|||

|

1-3 |

2.16 (1.88, 2.50)*** |

2.09 (1.81, 2.42)*** |

|

|

3+ |

2.01 (1.82, 2.23)*** |

2.03 (1.84, 2.25)*** |

|

|

Division |

|

|

|

|

Dhaka |

|||

|

Chattogram |

0.91 (0.79, 1.05) |

||

|

Mymensingh |

1.18 (0.97, 1.44) |

||

|

Rajshahi |

0.88 (0.73, 1.05) |

||

|

Khulna |

0.72 (0.61, 0.86)*** |

||

|

Rangpur |

0.99 (0.84, 1.18) |

||

|

Barisal |

0.8 (0.66, 0.96)** |

||

|

Sylhet |

1.28 (1.07, 1.52)*** |

||

|

Place delivery |

|

|

|

|

Private |

|||

|

Government |

1.21 (1.04, 1.40)** |

||

|

Home |

1.2 (1.06, 1.35)*** |

||

|

Wealth index |

|

|

|

|

Rich |

|||

|

Middle |

1.26 (1.08, 1.48)*** |

||

|

Poor |

1.65 (1.40, 1.96)*** |

*** p-value <0.001 and ** p-value <0.05

Model 1: Crude model- Prenatal care

Model2: Adjusted by mother and child factors: Prenatal care, Mother educational status, Mother age at birth, Internet, Happiness, Birth order, Gender, Child age

Model3: Adjusted by mother and child factors and socioeconomic conditions: Prenatal care, Mother educational status, Mother age at birth, Internet, Happiness, Birth order, Sex, Child age, Division, Place of delivery, Wealth index.

4. Discussion

This study shows that about 26.5 % of under-five-aged children are stunted, and the number of prenatal care taken by the mother is a significant risk factor. Children whose mothers did not take prenatal care were more likely to be stunted. As they are not consulting with health experts, they do not have enough knowledge about their health and their baby's health.

The Children are facing stunting in the long run. This scenario is almost the same for urban and rural areas as the percentage of a stunted children between urban and rural areas does not differ significantly. It is interesting to notice that the prevalence of stunting among boys is higher than that of girls. The recent government activities regarding various benefits provided to girl children might have played a vital role here. The comparison of child age indicates that, as the age of child increases, the odds of being stunted also increase significantly.

This is an alarming situation. Because if the children are suffering from malnutrition during the prime developing period and at the start of going to school, they will face difficulty becoming ideal people in their personal life and family, social, and national areas. Many studies suggest that maternal education is linked with child health outcomes.

It has been observed that odds are significantly higher among the mothers with no education or only primary education than mothers with higher secondary education. There are still about 40% of mothers who have not reached secondary or higher secondary education. This shows that many women are still not getting the appropriate education. Even though they are getting some education in primary school, it is not significantly contributing to taking care of her children's health development. Children living in the Khulna and Barisal divisions have a significantly low risk of stunting and a significantly higher risk of stunting found for those living in the Sylhet division compared to the Dhaka division.

While observing the effect of place of delivery, the child born in a government hospital and home were at higher risk of being stunted than those born in private hospitals. In-home and government hospitals, mothers are not getting enough awareness regarding their health issues and their children's health.

On the other hand, private hospitals charge a high cost while delivering. As a result, they are providing better service than others. Finally, this study has seen a vast difference between higher wealth quantile (rich) and lower wealth quantile (poor and middle). The children born in both poor and middle-class families are in vulnerable conditions compared to wealthy families. So, only the rich are getting better facilities due to economic inequality. They can afford child education at a higher level, private hospitals costs, and are also aware of prenatal care.

5. Strengths and limitation

The study's key strengths were that it was based on the most recent nationally representative demographic statistics with children, their households, and the places in which they live. Because the data were nationally representative, a large sample was used in this investigation.

As a result, child malnutrition in Bangladesh for children under the age of five is simply generalizable. Because cross-sectional data were employed in this investigation, any inferences concerning the causal influence of the variables were limited. The socioeconomic status of the households may alter between the time of the Survey and the time of the child, resulting in a biased outcome in this study. Due to an overwhelming number of missing values and non-response in the data set, certain crucial variables were inconsequential. Furthermore, certain key factors such as mothers' job status and BMI were not included in this study due to a lack of data.

6. Conclusion

Child nutrition is an imperative aspect of developing a healthy and skilled nation in the long run. It also determines the quality of life in many ways. But in Bangladesh, the overall child malnutrition status regarding stunting is still not eminently satisfying. There are several sectors where enormous advancement plans are needed to be implemented. Mainly, reaching health facilities to all economic classes is a crying need. The government should emphasize improving the facilities at government hospitals so that mothers can quickly come for prenatal care and take quality service while the delivery of the child occurs.

In all sectors, including public and private, are combined effort is obligatory to overcome this complex reality of child malnutrition in Bangladesh. In addition, special attention should be given to vulnerable groups such as lower-wealth Windex mothers. A healthy mother can give birth to healthy children. Thus, the intervention programs for improving the nutritional status of children must focus not only on children but also on their mother.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express gratitude to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) for permitting us to use the MICS 2019 data.

Authors' Contribution

MMI initiated the study and carried out the literature review. MMI and MTI conducted the data analysis, and MMI, MTI, and FMN prepared the manuscript draft. MMI, MTI, and FMN read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None declared

Source of Funding

Not supported by any funding body

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The technical committee approved the survey protocol of the Government of Bangladesh, led by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). The protocol included a Protection Protocol, which outlines the potential risks during the life cycle of the survey and management strategies to mitigate these. As the de-identified data for this study came from secondary sources, this study does not require ethical approval.

References

- Rice AL, Sacco L, Hyder A and Black RE. Malnutrition is an underlying cause of childhood deaths associated with infectious diseases in developing countries. Bulletin of World Health Organization 78 (2000): 1207-1221.

- UNICEF/WHO/World Bank. Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates (2020).

- World Health Organization Child Mortality Levels: Probability of Dying per 1000 live Births, Data by County (2010).

- McGregor GS, Cheung YB, Cueto S, Glewwe P, Richter L and Strupp B. Development potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. The Lancet 369 (2007): 60–70.

- De Onis M, Blössner M. The World Health Organization global database on child growth and malnutrition: methodology and applications, Int J Epidemiol 32 (2003):518–526.

- Talukder A. Factors associated with malnutrition among under-five children: illustration using Bangladesh demographic and health survey, 2014 data, Children 4 (2017): 88.

- World Health Organization, Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index for-Age: Methods and Development. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO: Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group (2006).

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2014; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, (2014).

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, and Macro International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Dhaka: NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International; NIPORT: Eklashpur, Bangladesh (2016).

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) and UNICEF Bangladesh. Progotir Pathey, Bangladesh Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2019, Survey Findings Report. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) (2019).

- Ahmed T, Ahmed AM, Reducing the burden of malnutrition in Bangladesh BMJ 339 (2009):1060.

- Siddique MNA, Haque MN and Goni MA. Malnutrition of under five children: Evidence from Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Medical Science 2 (2011): 113-119.

- Mohammad KA, Haque ME, Bari W, Does community facility play a vital role on nutrition status of under-five children in Bangladesh. Dhaka Univ J Sci 65 (2017): 27–33.

- Beiersmann C, Bermejo Lorenzo J, Bountogo M, Tiendrebeogo J, Gabrysch S,Yé M,et al. (2013) Malnutrition determinants in young children from Burkina Faso. J Trop Pediatr 59.

- Ergin F, Okyay P, Atasoylu G, Beser E. Nutritional status and risk factors of chronic malnutrition in children under five years of age in Aydin, a western city of Turkey. Turk J Pediatr 49 (2007): 283–289.

- Islam MM, Alam M, Tariquzaman M, Kabir MA, Pervin R, Begum M, et al. Predictors of the number of under-five malnourished children in Bangladesh: application of the generalized poisson regression model. BMC Public Health 13 (2013).

- Kabubo-Mariara J, Ndenge GK, Mwabu DK. Determinants of children's nutritional status in Kenya: evidence from demographic and health surveys. J Afr Economies 18 (2009).

- Islam, M.M., Bari, W. Analysing malnutrition status of urban children in Bangladesh: quantile regression modelling. J Public Health (Berl.)29, 815–822(2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01191-0

- Mishra K, Kumar P, Basu S, Rai K, Aneja S. Risk factors for severe acute malnutrition in children below 5 y of age in India: a case-control study. Indian J Pediatr 81 (2014): 762–765.

- Mozumder AB, Barket-E-Khuda, Kane TT, Levin A, Ahmed S. The Effect of Birth Interval on Malnutrition in Bangladeshi Infants and Young Children. Journal of biosocial science 32 (2000): 289–300.

- Rahman A, Chowdhury S. Determinants of Chronic Malnutrition among Preschool children in Bangladesh. Journal of Biosocial Science 39 (2007): 161–173.

- Rahman A, Chowdhury S, Hossain D. Acute Malnutrition in Bangladeshi Children. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health 21 (2009): 294–302.